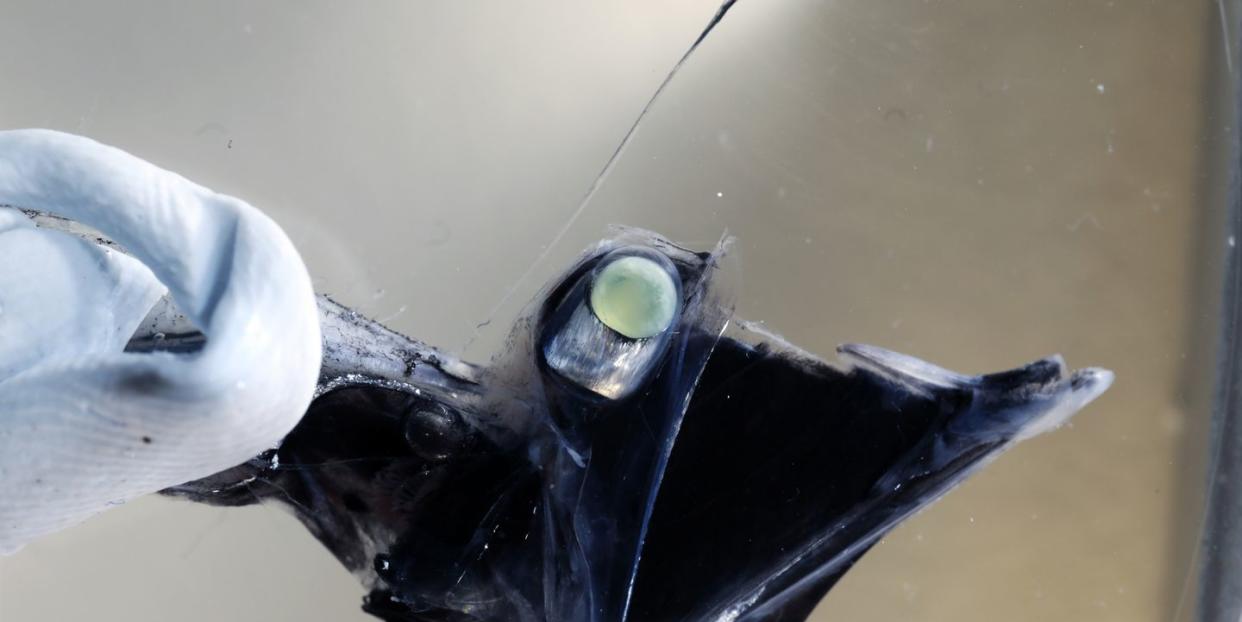

Some Fish Can See in Color at 5,000 Feet Below Sea Level

Nature is harsh. But over time, animals can evolve to adapt to that harshness with stunning methods.

Scientists have discovered a previously unknown visual system that may allow color vision in deep, dark waters–around 650 to 5,000 feet below sea level, where animals were presumed to be colorblind. The discovery forces a reconsideration of the underwater animals that live without sunlight.

“This is the first paper that examines a diverse set of fishes and finds how versatile and variable their visual systems can be,” says Karen Carleton, a biology professor at the University of Maryland and co-author of the paper, published as the cover story in this month's Science Advances, in a press statement.

“The genes that determine the spectrum of light our eyes are sensitive to turn out to be a much more variable set of genes, causing greater visual system evolution much more quickly than we anticipated.”

Vertebrae animals, like humans, require two types of photoreceptor cells to see, known as rods and cones. Rods and cones work similarly-they both contain tangled, light-sensitive pigments known as opsins. Ospins take in specific wavelengths of light and then convert them into electrochemical signals. The brain interprets those signals as color.

It's generally accepted that across vertebrae species, cones are responsible for color vision and rods for detecting brightness in dim conditions. However, this new study of 101 fish shows that there's diversity in how rods are used. Some of the fish contained multiple rod opsins, suggesting that they might have rod-based color vision.

Notably, silver spinyfin fish (Diretmus argenteus) turned out to have 38 rod opsin genes. No known fish have as many ospins in their cones, and it's the highest number of opsins found in any known vertebrate. For comparison, humans only have four ospins.

“This was very surprising,” Carleton says in the statement. “It means the silver spinyfin fish have very different visual capabilities than we thought. So, the question then is, what good is that? What could these fish use these spectrally different opsins for?”

Nobody knows for sure yet, but Carleton suspects it could have to do with hunting.

In the darkest depths of the sea, the few animals that live there sometimes generate their own light through the remarkable process of bioluminescence. Sometimes, species on lower rungs of the food chain, like the "green bomber" worm (Swima bombiviridis) use what are known as bioluminescent "bombs" to distract predators.

The extra ospins could be in place to allow predators to see through the smoke and mirrors.

“It may be that their vision is highly tuned to the different colors of light emitted from the different species they prey on,” Carleton says.

Vision is the name of the game in a place where there is no light. While some fish use bright lights, others have evolved into a state of translucence.

Source: CNet

('You Might Also Like',)