In a first, the life of trailblazing Black music leader from NC celebrated in a museum

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

A new Charlotte Museum of History exhibit aims to bring the story of a remarkable African American woman and trailblazing musician from North Carolina’s Piedmont region out of the shadows — Mary Cardwell Dawson.

Growing up in Pittsburgh, museum president and CEO Terri White remembers hearing stories about Dawson, who founded the first commercially successful Black opera company in the U.S. White also would walk by a dilapidated three-story Victorian house — now being restored as a historic monument — that once held a music school and was the headquarters of Dawson’s National Negro Opera Company.

Dawson started the company in 1941, at a time when segregation remained commonplace around the U.S. during Jim Crow. But she nurtured hundreds of artists there, organized opera guilds in a handful of big cities and advocated for arts and culture for all people.

Dawson was born two hours north of Charlotte in Madison, and she and her family relocated to Pittsburgh when Dawson was a young girl.

Dawson was one of many figures from the city’s proud Black history — including playwright August Wilson, legendary Negro League baseball teams, like the Homestead Grays and Pittsburgh Crawfords, and the influential Black newspaper, The Pittsburgh Courier — that White’s mother and teachers made sure she knew about.

“So when I moved here, I just assumed everybody knew this history,” White said. But in Charlotte most people were unaware of Dawson.

That lack of familiarity began to change last month, when opera star Denyce Graves and her foundation joined Opera Carolina to perform a play with music about Dawson’s life called “The Passion of Mary Cardwell Dawson.” The museum also collaborated on that work.

White hopes to further enhance people’s understanding about Dawson with a new exhibit at the museum, “Open Wide the Door: The Story of Mary Cardwell Dawson and the National Negro Opera Company.” It opens March 26 at The Charlotte Museum of History, and is part of a partnership with Charlotte’s opera company.

What’s more, this is the first time any museum has staged an exhibit about Dawson, according to the Charlotte Museum of History.

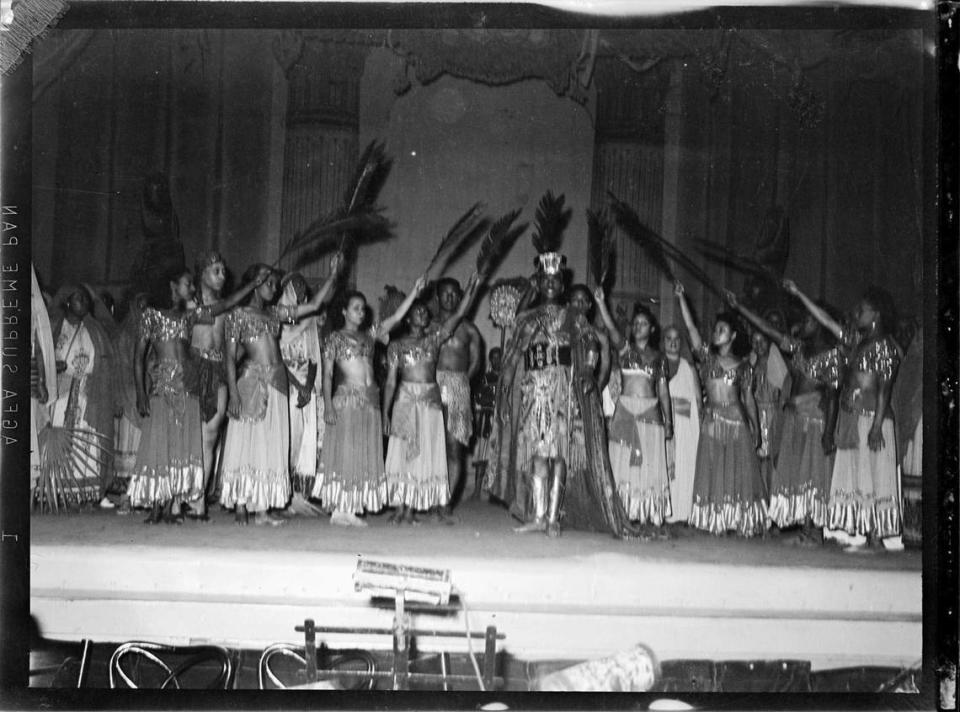

Through vintage photos, original costumes and historic documents, the exhibit delves into Dawson’s story as well as that of other North Carolina-born performers who were part of her company and legacy.

The exhibit also highlights the long tradition of Black artists in opera and classical music, and the prevalence of opera in cultures around the world, from Latin America to Korea.

Who was Mary Cardwell Dawson?

Dawson, born in Madison in 1894, was an opera singer and pianist, and the only Black student in her class at the New England Conservatory. Because systemic racism limited employment opportunities as a performer, Dawson focused on teaching.

She started her own music school in the 1920s, established a choir and founded the highly regarded National Negro Opera Company, which had its first performance in 1941.

Over the 20 years it ran, the opera company toured the country and put about 1,800 performers on stage.

Dawson demanded excellence from her students and performers, and insisted her singers be admitted to an artists’ union. She refused to hold performances in any houses with segregated seating.

The opera company also made history in 1956 as the first African American group allowed to rent New York’s Metropolitan Opera House. That’s where it presented a concert version of Clarence Cameron White’s “Ouanga,” the first opera by a Black composer ever performed in the hall. (The Met Opera didn’t present a work by a Black composer until 2021 with Terence Blanchard’s “Fire Shut Up in My Bones.”)

But Dawson’s company’s repertoire also included fully staged productions of European grand operas like Verdi’s “Aida” and “La Traviata,” and Gounod’s “Faust.”

Dawson’s influence and connections to other outstanding artists were widespread.

She taught celebrated jazz pianist Ahmad Jamal, and worked with performers like Robert McFerrin Sr., who became the first Black male soloist with The Met, Broadway star Napoleon Reed and soprano Lillian Evante — who had already performed across Europe but made her American opera debut with Dawson’s company.

At the Mary Cardwell Dawson exhibit

The exhibition features artifacts, including five original National Negro Opera Company costumes on loan from the Heinz History Center, dozens of photos, reproductions of flyers, programs and letters from collections housed at the Smithsonian Museum and Library of Congress.

Other items on display include modern costumes and set pieces from Opera Carolina’s 2022 production of “Aida,” including two giant anubis dog statues that White and her team were trying to figure out how to transport the day she spoke with the Observer.

“It’s not a normal thing,” she said with a laugh. “You can’t just throw that in the back of your car.”

Teaming up with Opera Carolina

The museum and Opera Carolina have been supporting each other in other ways, too.

In the fall of 2022, several months after joining the museum, White began researching potential performance partners in conjunction with the planned exhibit. She contacted Maestro James Meena, Opera Carolina’s general and artistic director, and discovered two things.

First, Meena had deep connections to Pittsburgh. He’s a graduate of Carnegie Mellon University and made his professional and operatic debuts in that city.

And second, the opera was also considering presenting a work tied to the same history, through its relationship with Graves. At Meena’s suggestion, they decided to collaborate on both projects together.

Graves also credits Dawson as the inspiration behind her non-profit, The Denyce Graves Foundation. Its mission is “to promote equity and inclusion in American classical vocal arts through an unprecedented approach: championing the hidden musical figures of the past while uplifting young artists of world-class talent from all backgrounds.”

‘They deserve to be remembered’

The National Negro Opera Company was not the first Black professional company, though it is sometimes misidentified as such, according to musicologist Karen Bryan. She has been studying Dawson since the 1990s and is writing a biography on her and the opera company.

Dawson continued the legacy of other African American artists and competed with other contemporary Black companies. “She was one of the first African American women to establish and manage a long-term opera company,” said Bryan, who also heads the Hidden Voices program for Graves’ foundation.

In recent decades, scholars like Bryan have been trying to restore the history of Black performers in opera and other classical forms of music.

“These people deserve to be known,” she said. “They deserve to be remembered.

“All of the opera singers were omitted from the narrative,” she said. “The story of opera in this country was white and very much so... Most of the stories that you got were the stories of the major companies, and they were not hiring Black singers at the time.

“There was a very real and prevailing attitude that most Black singers should go into spirituals or jazz or popular music or something like that.”

Bryan said that a line in the play, in which Dawson recounts a man in the union saying “we all know Negroes can’t sing grand opera,” actually happened. And so did Dawson’s response: she slapped him.

‘A really cool American story’

White hopes visitors will connect with the exhibition and leave with new insights.

“Even if you hate opera, even if you’re not interested in Black history,” White said, “I think it’s a really cool American story that this woman who, by all accounts, should not have been able to do half the things she did, had enough gumption and stubbornness to say ‘No, I’m gonna do it anyway.’ ”

It’s also a story that shows geography does not dictate destiny.

You don’t have to come from New York or L.A. “to have this massive influence on the culture,” White said. “These are people from small towns... but who were obviously talented and brave enough to share their gifts with the world.”

She hopes the exhibit will help democratize opera, too, an art form which battles its own stereotypes.

It’s not “one type of person’s music,” White said. “...This is for everybody. If you enjoy the music, if you enjoy the costumes and the makeup artistry and all that, this is for you.”

One more thing: White noted that Dawson died in 1962 at age 68 after her second heart attack, having spent much of her career under constant stress seeking funding for her work. White doesn’t want such dire stress to happen to her.

She urged the community to support arts and cultural organizations like the museum which, she said, receives no operational funding from the city, county or state. With strong public support, arts and cultural groups can continue to bring groundbreaking exhibits like the one about Dawson.

Want to go?

What: “Open Wide the Door: The Story of Mary Cardwell Dawson and the National Negro Opera Company.”

Where: Charlotte Museum of History, 3500 Shamrock Drive, Charlotte.

When: March 26-Dec. 31.

For tickets: https://charlottemuseum.org/visit/purchase-tickets/

More arts coverage

Want to see more stories like this? Sign up here for our free “Inside Charlotte Arts” newsletter: charlotteobserver.com/newsletters. And you can join our Facebook group, “Inside Charlotte Arts,” by going here: facebook.com/groups/insidecharlottearts.