Fire in remote Alaska village leaves COVID-19-racked residents without safe drinking water

Kyle Peter pounded on Nelson and Kristy Napoka’s front door, urgency in every knock.

“The washeteria is on fire!” he burst out when his sister’s door opened.

Kristy had been cooking a turkey for her daughter's birthday, but a threat to the village's only source of treated drinking water spurred her to action. She threw on her dark purple coat. Nelson dropped the diced moose meat with steamed jasmine rice he had been eating and ran outside.

It was Jan. 16, around 11 a.m. With no running water to the homes in Tuluksak, Alaska, most residents relied on the water piped to the village's laundry building, which also housed the water treatment plant. Now, thick smoke poured through cracks in the building and from under the doors. The only hope to put it out was with a hose – which was in the burning building.

Even with no one inside the building, the danger was great. If the fire reached the two 18,000-gallon fuel tanks 35 feet away from the building or the Napokas’ house, just 50 feet away, the damage could be catastrophic.

Nelson Napoka ran to one door. Locked. He ran to another. Locked again.

They needed that hose.

Napoka raced home to get his ax.

Tuluksak, a 457-resident village in southwest Alaska, is among the most rural places in the country’s 49th state. No roads connect it to nearby villages. A 400-mile trip from Anchorage takes two plane rides. Since everything needs to be flown into the village, life in Tuluksak is expensive. A case of water costs up to $61; a 10-pound bag of sugar, $22; a half-gallon of orange juice, $12. About half of residents live in poverty, and many use food stamps.

Despite the isolation, the coronavirus has hit rural Alaska hard. About one-third of Tuluksak's residents have been diagnosed with COVID-19, and like many other villages Tuluksak is on lockdown. A beloved dog sled driver, Joe Demantle Jr., recently died from the virus. The school has been closed since October.

But for these Alaska Natives – most of whom belong to the Tuluksak Native Community tribe and have lived here for generations – this is home. In the winter, they ride snowmobiles in temperatures that often drop far below zero. In the summer, they fish on boats in 65-degree sunshine while the kids ride bikes and play basketball. Living off the land is a year-long endeavor: catching and drying fish, berry picking, ice-fishing, and hunting. It’s a community where hunters share their moose and bears with the tribe’s elders.

The people, the natural beauty, the shared sense of family: that’s what keeps residents devoted to the remote village.

“I love it because I grew up here,” said 33-year-old Kristy Napoka, secretary-treasurer of the tribe and utilities manager. “Everyone knows one another, and if something bad were to happen, everyone comes together and works together. I love everything about where I live. It’s beautiful.”

But being so remote can leave a village vulnerable to disaster. When trouble hits, help takes time to arrive. A few years ago, the community’s power plant kept breaking down and the village went days without electricity, ruining freezers full of meat before parts arrived and repairs could be made.

So when thick black smoke engulfed the tan, wood-framed washeteria, villagers knew they couldn’t wait on help; Tuluksak doesn’t have a fire department. If they were going to prevent the disaster from getting any worse, they would have to pull together.

A fight in vain

Nelson Napoka slammed his ax into the door of the washeteria, breaking the lock and releasing a hot plume of smoke into his face. Maybe another door would be better. He ran to a different one, breaking another lock. Just more smoke.

Napoka – a 42-year-old maintenance man for the area health clinic – knew where the hose was. Somehow, he stepped inside far enough to grab it and pull. But the hose was stuck on something and the smoke was too thick. Napoka dropped it and retreated.

Kyle Peter, 27, crawled underneath the building with a fire extinguisher, hoping to douse the blaze. Chemicals were leaking on the ground. Peter abandoned his mission.

Napoka’s mind went blank. There was no running water. What could they do? Fire was now tearing through the building, red and orange flames lurching from the washeteria as the oxygen fueled its spread.

Bobby Peter – Kristy Napoka and Kyle Peter’s 60-year-old uncle – ran to the scene. He had fire training and had dealt with house, school and nature blazes, all of which they’d managed to control.

Peter assessed the situation and tried to stay calm.

We need volunteers. We need the river water. We need to keep the little kids away from the fire. We can’t let it spread to the fuel tanks.

By now, 50 or 60 residents had raced to the scene to help. They jumped on their ATVs and snowmobiles, sleds filled with empty buckets dragging behind as they rushed toward the Tuluksak River between 200 and 300 feet away. After cutting a hole in the frozen water with an outdoor ice pick, they filled buckets of water, hauled them to the burning building and tossed the water at the flames.

They knew the washeteria was a loss. But they had to keep the fuel lines to the nearby fuel tanks cool, packing them in snow to protect them from the fire’s heat. They threw buckets of water on the Napokas’ house to repel the fire.

On and on it went for hours as the fire continued to reignite from chemicals the water couldn’t douse. By dark, the fire was out. The washeteria was destroyed, but the fuel tanks were safe and volunteers had saved the Napokas’ house.

Bobby Peter was exhausted. He couldn’t lift another bucket. He was hungry.

He made his way home, pulled off his soaking wet boots, collapsed on his daughter’s bed and fell asleep on top of the blankets.

'They need water'

The next day, the shock was still setting in. The washeteria and water plant, which was about 40 years old, had been the only source of cheap, clean water in the village. The Tuluksak Native Community, which owned the facility, sold water for 25 cents a gallon.

Residents have long complained to state officials that they believe the Tuluksak River has been poisoned by upriver gold mining and they refuse to drink the discolored water. Officials with the state's Division of Homeland Security and Emergency Management said as much in an interview with USA TODAY, adding that residents should draw water from the Kuskokwim River 2 miles away. But in response to follow-up questions from the newspaper, Alaska's Department of Environmental Conservation said this week it has no evidence that the water is contaminated with heavy metals, explaining that high iron levels cause its orangish color and that it is drinkable if boiled properly. Several residents said they still will not drink it.

Tribal administrator Elsie Allain – a 41-year-old mother who has six children and a seventh on the way – said her family had just refilled their water supply before the fire. They also filled their buckets with fresh snow and rain. She had also been stocking up bottled water from the store.

But with her big family, it wouldn’t last long.

“I’m just happy that my husband and I were collecting water before anything happened to the laundromat,” Allain said.

More than 2,600 miles away in Los Angeles, CeeJay Johnson had learned about the fire. A 33-year-old artist who was raised in Sitka, Alaska, Johnson had already been raising money for rural Alaska communities struggling with COVID-19. She connected with Allain’s sister, Angie Lott, in Anchorage to get bottled water to the scores of families without clean water.

“I was really worried,” Lott said. “Elsie’s pregnant and I couldn’t get it out of my mind: They need water, they need water, they need water.”

Within five days, the pair had managed to send 20 cases of water to the village. But it wasn’t cheap. It cost $1,000 to ship $100 worth of water. And both women knew they’d have to amp up their efforts to get enough water to serve the whole town. So Johnson switched the focus of her GoFundMe page from COVID-19 support to funds for fresh water for Tuluksak. To date, that page has raised more than $100,000.

Meanwhile, cargo planes volunteered their services or reduced their fees; indigenous rapper Taboo of the Black Eyed Peas donated pallets of spring water; Donlin Gold – which is trying to build a mine upstream from the village – sent supplies; and the federal Bureau of Indian Affairs and the local health corporation sent water.

As days turned into weeks, Tuluksak residents and supporters grew increasingly anxious. How much longer could they depend on donations? Where was the Federal Emergency Management Agency or Alaska National Guard? Why hadn’t Gov. Mike Dunleavy issued a disaster declaration to help the village qualify for aid toward a solution?

Getting infrastructure is a common problem in rural Alaska because of the state’s sheer size, said Jennifer Schmidt, an assistant professor with the University of Alaska Anchorage who has studied rural communities in the state. Some isolated villages live without basic amenities such as running water because it’s so expensive to bring materials to the area. Some, like Tuluksak, don’t even have roads year-round. Everything has to be flown or shipped in by barge. And when a water plant is constructed in such areas, local people need to be trained to maintain the facility.

Then there’s the cost of it.

“It’s a matter of funding,” Schmidt said. “Water treatment plants are very, very expensive and you need outside funding from someone like the state.”

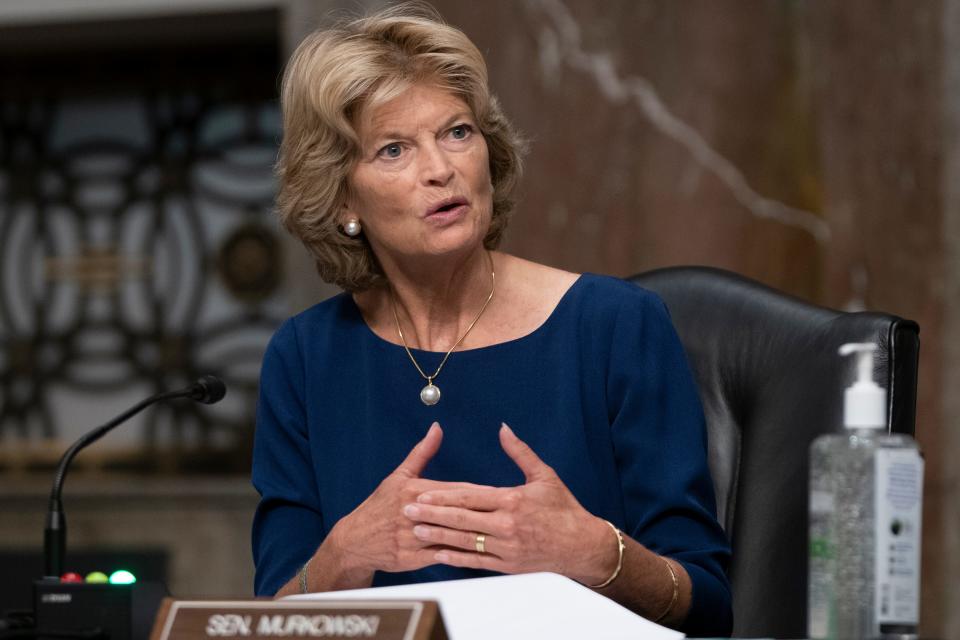

Social media campaigns called on state and federal officials, like U.S. Sen. Lisa Murkowski, R-Alaska, to force the state to take immediate action. Alaska news outlets wrote numerous stories about the water plant fire. Residents suspect the fire was caused because the lint trap in a dryer had not been emptied.

Murkowski told USA TODAY in early February that she didn’t know about the fire in Tuluksak until a staffer saw it on Facebook.

“I thought, is this the best we can do?” she said. “A GoFundMe site out of California? Who is doing what here?”

Murkowski said she and her team began talking to government agencies, urging them to work together quickly. She put the incident in the category of a disaster, she said. While she appreciated the intermediate and long-term plans for the village, she encouraged agencies to get Tuluksak the immediate help they needed.

“Help can not come fast enough,” she said. “Water is water.”

Regional organizations such as the Yukon-Kuskokwim Health Corp. stepped up with intermediate solutions. The group plans to build a temporary water plant where residents can do laundry and get water for cleaning and also a temporary treatment plant that would provide drinkable water. State officials say they have been involved in these conversations and been monitoring the water situation.

On Feb. 8, more than three weeks after the fire wiped out the water plant, Gov. Dunleavy signed a disaster declaration, which freed $1 million in state funds to help the village. What the $1 million will be spent on is not yet clear, but it won’t fund bottled water for Tuluksak, said Jeremy Zidek, spokesman for the Alaska Division of Homeland Security and Emergency Management.

“That immediate need for water has been met,” he said.

It also appears that Tuluksak will get the long-term help it needs. This week, the federal Indian Health Service told the village it had approved a $6.5 million grant to replace the water treatment plant. The Denali Commission – an Alaska-based, federal agency that provides utilities, infrastructure, and economic support throughout the state – has agreed to contribute about $200,000 toward the effort. Construction will begin in summer 2022.

Making do

In the meantime, Tuluksak’s villagers are making do the best they can, just as they did the day of the fire.

The Napoka family gets their water from the Kuskokwim. Several times a week, Nelson Napoka and three of his six children ride the trails on their snowmobile or walk along the frozen river, loading 40-70 gallons of water on sleds.

When the wind blows, it can hit 20 degrees below zero, he said.

Napoka is among those who think state officials don’t seem to understand the severity of the situation.

“I’d like for them to come out here and see what we’re dealing with at this moment,” Napoka said. “But they really don’t want to know what’s going on in the villages or the towns. They just listen to stories.”

Tribal police officer Yvonne Alexie has it even harder. She doesn’t have a snowmobile or an ATV to get to the Kuskokwim River, and she doesn’t have the money to buy water at the store.

So when they run out of donated water, she and her three children are drinking from the Tuluksak River that most of her neighbors believe isn’t safe.

She doesn’t feel good about it. The water is “gross and yellowish,” she said. It tastes like metal. But for now she feels she has no choice.

“It’s not healthy for us,” she said.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: COVID-19-racked Alaskan village without safe drinking water after fire