Fiona Hill, Trump's top expert on Russia, is quietly shaping a tougher U.S. policy

WASHINGTON — Three days after Chechen terrorists killed more than 300 people at a school they’d seized in southern Russia in 2004, Fiona Hill, a British-American scholar, visited Russian President Vladimir Putin at Novo-Ogaryovo, his estate outside of Moscow.

Hill was part of a delegation of Westerners invited to hear about how the Kremlin planned to counter the insurgency that had roiled Chechnya for more than a decade. She came away impressed and at least partially convinced, as she made evident in an op-ed subsequently published in the New York Times: “Stop Blaming Putin and Start Helping Him.”

Last summer, Hill sat across from the Russian president once again. This time, the setting was the presidential palace in Helsinki, at the bilateral summit between Putin and President Trump. Hill, who’d joined the National Security Council two months into the Trump presidency as director of Russian and European affairs, sat between White House chief of staff John Kelly and Secretary of State Mike Pompeo at a working lunch with senior diplomats. She was one of only two women in the room.

Coverage of the Helsinki summit focused on the joint press conference afterward, during which the American president declined to reprimand his Russian counterpart for interfering in the 2016 elections.

But Helsinki also represented a remarkable achievement for a woman who may understand Putin better than anyone in the American foreign policy establishment. Even more remarkable is that she has brought that expertise to an administration that has been accused of coddling the Kremlin.

For nearly two decades, Hill has followed Putin’s trajectory, from the glum apparatchik presiding over the chaotic post-Yeltsin years to the modern-day czar who flouts international law and is suspected of hiding tens of billions of dollars in personal wealth abroad. That has earned her a top position in a White House split between those who admire the Kremlin and those who fear it. Between them stands a coal miner’s daughter, trying to negotiate a path both factions can countenance.

Trump has bestowed considerable authority on a woman who has none of the usual markers of influence in the Trump administration. Hill is not a billionaire, nor a Fox News regular. She does not golf or tweet. In a city of partisanship and self-promotion, Hill eschews both. People who’ve known her for years profess not to know her political affiliation.

In that sense, she’s almost certainly not part of the “resistance” described in a recent op-ed in the New York Times by a senior member of the Trump administration, who praised the president’s national security team for countering Trump’s worst instincts, including his “preference for autocrats and dictators, such as President Vladimir Putin of Russia.” Hill was proposed by some, including CNN’s Chris Cillizza, as the author of the op-ed. But at least one person who knows her says that’s impossible. Little in her career suggests the kind of sly political maneuvering the Times op-ed represented.

Yet Hill and her peers have managed to craft a Russia policy that is, by any measure — sanctions, expulsions, military buildup — tougher than that of the Obama administration. Trump has not always championed this approach, but he apparently hasn’t hindered Hill and her colleagues on the National Security Council or in the State Department from doing their work. He has, in effect, sanctioned a Russia policy that is entirely at odds with his own pronouncements.

One person who knows Hill well and worked with her on the NSC says Hill is not a Russia “hawk,” a term that suggests a desire for war, but “a realist,” one who “doesn’t want to be duped by the Russians,” the former official said, speaking on the condition of anonymity in order not to jeopardize past or present professional affiliations. Hill, whom the NSC declined to make available for an interview, is also unlikely to be rattled by Trump’s tweets, or by the baroque shows of disloyalty that regularly emanate from the White House. “Her job is not to keep up with the craziness of D.C.,” the former official said. That may be why Hill has kept her job, even as many around her have lost theirs.

*****

When Hill was first mentioned in March 2017 as a likely NSC appointee, the development became a minor sensation in the British press. “Revealed: Coal miner’s daughter from County Durham set to be Donald Trump’s top adviser on Russia,” said the Mirror. For a society still bound in part by centuries-old class strictures, it was remarkable that a woman of “very modest circumstances,” as Russia expert and Hill ally Angela Stent of Georgetown puts it, was able to reach the highest ranks of American society.

Hill was born in England near the end of 1965, a year that began with the death of Winston Churchill. Bishop Auckland, where the Hills lived, was an industrial town in northeast England, once known as a major ecclesiastical center.

By the 1960s, however, the prospects in Bishop Auckland were starting to fade. Hill grew up in what she would later call a “working-class” household. Her mother, June, was a midwife at Bishop Auckland General Hospital, while her father, Alfred, worked at the Woolley Colliery coal mine. There is little indication that much was expected of her, given the circumstances of her childhood. “She grew up in an area where the schools were pretty bad,” Stent says.

When the Guardian newspaper held a conversation on class in 2016, Hill was one of the participants. “I applied to Oxford in the ’80s and was invited to an interview. It was like a scene from ‘Billy Elliot,’” she recalled, alluding to the 2000 film about a boy from her native County Durham who overcomes his impoverished beginnings to become a ballet dancer. “People were making fun of me for my accent and the way I was dressed,” Hill said. “It was the most embarrassing, awful experience I had ever had in my life.”

Hill went instead to the University of St. Andrews in Scotland, where she studied Russian and history. She spent two years studying Russian at the Maurice Thorez Institute of Foreign Languages in Moscow. (Hill’s time at the Thorez Institute later became the basis for one of the several competing — and conflicting — conspiracy theories about her.) While studying in Moscow, she also worked as an intern for Maria Shriver, then a host of NBC’s “Today” show.

Encouraged by an American academic she met through the internship, Hill applied and was admitted to Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government. She arrived in 1991, just as the Soviet Union was in the final throes of collapse. “Absolutely everything I’ve done — my research, my training, my book — was made possible due to Harvard opening doors and providing me with connections,” Hill said many years later.

Hill would spend the following seven years in Cambridge, Mass., earning her PhD from Harvard in 1998, while also traveling extensively through the Soviet Union, including to restive regions like Chechnya and the Caucasus. It was early during her time at Harvard that Hill met her future husband, Kenneth Keen, a senior partner in the Washington office of the Boston Consulting Group, the influential firm where Mitt Romney had his first job.

Among Hill’s mentors at Harvard was Richard Pipes, the Jewish American historian whose family had escaped Poland just ahead of the Nazi invasion. Pipes was among the nation’s leading hard-liners, and remained so even after others concluded that the Soviet Union ceased to be a threat. Pipes’s assessment about the Kremlin’s intractability, about a nation frequently wounded but never cowed, clearly left a mark on Hill.

Hill completed her PhD at Harvard with a dissertation titled “In Search of Great Russia: Elites, Ideas, Power, the State, and the Pre-Revolutionary Past in the New Russia, 1991-1996.” In a journal article based on the dissertation, Hill wrote of Russia’s “political elites” seeking “inspiration from their counterparts in late imperial Russia,” in particular regarding “restoring past glories and maintaining Russia’s geopolitical status as a Great Power.”

The West was expecting post-Soviet Russia to look forward, to declare a definitive break with its own past. But years before Putin began the rehabilitation of the Soviet Union, Hill had grasped how profoundly Russia is governed by its own centuries-old psychodramas, which have frequently proved immune to Western ideas, democracy among them.

*****

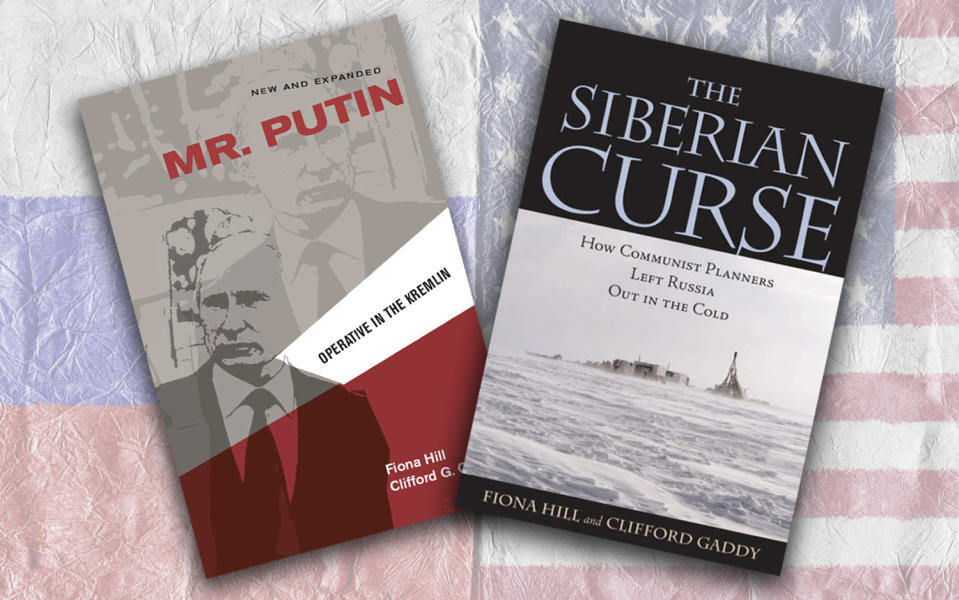

When Hill published her first book, in 2003, dispatches from hypercapitalist, enthrallingly dangerous Moscow were turning into a kind of genre. Her book, by contrast, was about Siberia. Co-authored with Clifford Gaddy, “The Siberian Curse: How Communist Planners Left Russia Out in the Cold” identified the vast, frozen hinterlands of eastern Russia as crucial to understanding the nation’s failures and aspirations. In a novel argument, Hill and Gaddy offered that Siberia was an important relic of Russia’s imperial past, only one that harmed Russia’s present by drawing people and resources away from the urban centers on the country’s western edge.

At the time “The Siberian Curse” was published, Hill had spent three years at the Brookings Institution, the center-left Washington, D.C., think tank. She would spend three more years at Brookings, before spending another three as an intelligence officer at the U.S. National Intelligence Council, her work focusing on Russia. She returned to Brookings in 2009, though not in any apparent search for a coveted Washington sinecure. “The concept of public service is very important for her,” explains Stent of Georgetown. “Maybe it’s because she is an immigrant.”

U.S. relations with Russia rapidly deteriorated during the presidency of Barack Obama, who seemed not to know how to confront a nation so grandiose and tragic, a shortcoming shared by his two secretaries of state, Hillary Clinton and John Kerry. After a “reset” of relations failed, both sides approached each other with increasing suspicion. Hill too no longer trusted Putin as the leader who, in 2004, could credibly ask for Western patience, if not Western cooperation.

Returning in 2011 from what had become an annual meeting with Westerners at Novo-Ogaryovo, Hill noticed that Putin had grown impatient and perhaps even bored with his audience. Then completing his term as Russia’s premier, expecting to return to the presidency with minimum opposition, he no longer felt the need to make overtures to skeptics outside Russia.

Back home, Hill recounted at length Putin’s grievances against the United States, in particular regarding missile defense and energy. But she also picked up the kinds of telling details that might have escaped an academic, but would have been crucial to an intelligence officer: that he came in “extraordinarily late” and did not apologize; that he had looked at his watch “as if he had got a bit fed up with the meeting,” which she had never seen him do before; that Dmitry Peskov, his press secretary, kept handing Putin notes.

Hill was sitting close enough to see that the notes were written in a large font, which led her to conclude that Putin must have been farsighted, a condition she surmised he was trying to hide because “a man of his vigor and superior physical attributes would not want to be seen wearing glasses.” Aware that some might not grasp the consequence of that detail, Hill argued that Putin’s potentially poor eyesight was “not just a trivial observation, a bit of color from the dinner. It sums up the fact that he has this image that he has to keep up at all times. He just cannot let his guard down. Any sign of frailty or any sign of confusion must be avoided.”

In 2013, Hill and Gaddy published “Mr. Putin: Operative in the Kremlin,” a book that has been universally praised for its cool, historical analysis of the unknown KGB officer who’d never taken part in an election before the one in which he ran, successfully, for the presidency. He hasn’t come close to losing one since. Hill and Gaddy portray Putin as a leader acutely attuned to Russia’s historical grievances, eager to restore a sense of national pride. “Vladimir Putin has ruled in the name of unity, of a united Russia,” they wrote presciently in the book’s conclusion. “But the unity he has created is superficial and fragile.”

Former CIA analyst Daniel Hoffman calls the book “the best analysis of what makes Vladimir Putin tick that anyone has ever written,” echoing a refrain about “Mr. Putin” that has come to be something of conventional wisdom.

During the 2016 presidential race, Hill remained outwardly neutral even as many other foreign policy experts warned loudly about the danger a Trump presidency would face. Some of them — most notably, veteran conservative foreign policy expert Elliott Abrams — later lost out on senior positions because Trump learned of their criticisms. Hill had no such record.

Hill appeared on Fox News a week after the election, where she was interviewed by foreign affairs expert K.T. McFarland, who noted that Putin had been the first to congratulate Trump on his victory over Clinton. McFarland asked if Russia really had hacked into the Clinton campaign; Hill said they had, an unpopular position in Trumpian circles. Two days later, Flynn was appointed the national security adviser, and chose McFarland as his deputy.

Hill was picked for the NSC by Flynn, whose tenure was reduced to a mere three weeks because he appeared to have had improper contact with Russian Ambassador Sergey Kislyak during the presidential transition. By the time Hill’s appointment was first reported, on March 2, 2017, H.R. McMaster was already in charge of the NSC. McMaster was widely praised for his cerebral approach to foreign policy. Hill, observers said, would help him tame Trump’s erratic impulses.

*****

In mid-April 2017, two U.S. Navy warships and one submarine fired a combined 59 Tomahawk cruise missiles at the Al Shayrat airfield in western Syria to punish Syrian President Bashar Assad for using chemical weapons against a rebel-held city. After the strike, Trump sought to calm potential tensions with Putin, Syria’s ally, and convened a meeting in the Oval Office ahead of a call to the Kremlin.

The episode underscores the difficulty Hill faced on the NSC, caught as she was between two strong-willed men. Reports about Hill’s time on the NSC during McMaster’s tenure differ. Some say that they were allies, bound by a shared understanding of how the United States could continue to exert its influence in a world no longer governed by antipodal superpowers. McMaster, like Hill, has the reputation of a serious thinker not especially interested in the kind of celebrity Trump tends to reward.

Others say that is a simplistic, even naive, portrayal. One former NSC official who worked closely with Hill says that “McMaster treated her terribly.” The former NSC official says that Hill was “undervalued,” despite being the top Russia expert in the federal government. (A request for comment from McMaster was not answered by the Hoover Institution, the conservative think tank where he is now a fellow.)

Hill also became the subject of conspiracy theories. Roger Stone, the longtime Trump confidant, was among those who called Hill a “mole” of George Soros, the Hungarian-American liberal philanthropist who has been the subject of many anti-Semitic fantasies. The charge, which is without evidence, stems from Hill’s position on an advisory board for the Open Society Institute, a Soros-funded pro-democracy group. An even more outlandish conspiracy theory had Hill as a plant of Putin in the White House, since the Thorez Institute in Moscow, where she once studied, is popular with agents of Russia’s security services. This also belongs to the realm of fantasy.

Trump, who never truly got along with McMaster, dismissed him as national security adviser in March, to the surprise of virtually no one in Washington. As he departed his office at the Eisenhower Executive Office Building next to the White House, McMaster assessed the challenges ahead. “Russia brazenly and implausibly denies its actions,” he warned, not needing to say that Trump was among the deniers. “We have failed to impose sufficient costs” on Russian aggression, McMaster added.

Hill is now working for the third national security adviser of the Trump administration, John Bolton. Unlike Hill, Bolton does not shy away from the camera. A routine presence on Fox News, Bolton got the attention of Trump, who liked his blustery, aggressive style. Bolton’s arrival at the NSC was marked by a number of departures, in a signal that he would remake the organization in his own image. Among those who left was retired Col. Richard Hooker, who worked on issues related to Russia and Europe at the NSC. Some say he was a natural Hill ally, though others have described him as difficult. (Hooker did not respond to multiple requests for comment sent to his personal email account.) Nadia Schadlow, a widely respected Russia expert, also left the NSC around the time of Bolton’s arrival.

That has left Hill the remaining Russia expert on the NSC, even as Bolton remains focused on Iran, his longstanding bête noire. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo is more engaged than his predecessor, Rex W. Tillerson, but that engagement appears almost exclusively focused on salvaging a nuclear deal with North Korea. Hill does have a counterpart at the State Department, A. Wess Mitchell, who is well-regarded, but his portfolio appears to encompass all of Eastern Europe, not just Russia.

“I’m glad Ambassador Bolton kept her on,” says Strobe Talbott, former president of the Brookings Institution, in reference to the mass exodus of NSC officials.

“She is there in the old Executive Office Building, right next to the White House,” Talbott says, “and I just assume, since she does come to work every day, and they are long days, that responsible officials are seeking her advice a lot of the time.

“The more they would take it, the better I would sleep at night.”

_____

Read more from Yahoo News: