Finding John Stockton

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

“I had to be famous for a reason,” John Stockton tells me, hanging on the last word. The phrase comes out more as a confession than a declaration, as if Stockton, himself, were grappling with just what to make of his basketball career. Those ballplaying days are now two decades in the past — a prestigious chapter, but a prelude nonetheless. Now, the man heralded as one of basketball’s greatest point guards ever wants to be known for something else.

“It’s a double-edged sword, fame is,” Stockton tells me, sitting on the old Delta Center wood court, now installed in a facility near Stockton’s home in Spokane, Washington. “There’s something I’m not —”

He stops himself midsentence. It seems there is something he wants to say, but doesn’t quite know how. When he reopens his mouth, his voice is hushed. “I haven’t answered the call yet, so to speak.”

It’s a surprising admission from a Hall of Famer. But there was always more than basketball to Stockton. Since his retirement in 2003, he’s led an unassuming life, moving back to his hometown and sequestering himself in Spokane’s quietness. He’s continued with the almost paranoid privacy that permeated his playing days: To avoid signature-seeking fans, he would hide in airport corners; to bypass journalists, he’d slip out of back doors. Not much changed after he stopped playing. He largely shuns the media and avoids public attention, preferring quiet time with his family, where he found purpose coaching his children’s sports teams. When the Jazz decided to retire his jersey, selling him on a lavish ceremony and pulling him back to Salt Lake City was a major feat.

All the while, the other famous players of Stockton’s era each seemed to slip back into the NBA’s orbit. Jordan, who beat Stockton in the Finals twice, bought an NBA franchise. Barkley and Magic donned suits for halftime shows. Bird, Kidd and Kerr got pro coaching gigs. Stockton, meanwhile, was content to coach Little League.

Then the COVID-19 pandemic hit, and for the first time in years, Stockton reemerged. But the foray had little to do with basketball. He first appeared in a documentary — “Covid and the Vaccine: Truth, Lies and Misconceptions Revealed” — which YouTube later removed, citing a violation of its “misinformation policies.” He refused to wear a mask to basketball games at his alma mater, Gonzaga University, leading the school to revoke his season tickets. He made frequent appearances on the kinds of podcasts that hawk gold bars between segments, expressing doubt about vaccines and pandemic lockdowns. He defended Kyrie Irving, the then-Brooklyn Nets guard who refused to comply with the NBA’s vaccine mandate.

Before long, Stockton’s pandemic commentary was no longer spontaneous. He started his own podcast, “Voices for Medical Freedom,” with Ken Ruettgers, a former NFL player. They both endorsed Robert F. Kennedy Jr. for president during a Fox News hit in November. Kennedy has reciprocated: The independent presidential candidate has encouraged Stockton to run for governor of Washington. (Stockton, for his part, said his interest was “fleeting.”)

For some of Stockton’s longtime fans, who recognize him more as a basketball player than an activist, it was a surprising, even uncomfortable, rebrand. They aren’t alone: It’s a new, uncomfortable world for Stockton, too. “I much prefer the quiet life,” he told me. “It’s easier. You don’t have to be ‘on’ all the time.” Stockton is quickly relearning the repercussions of life in the spotlight.

If getting ahold of Stockton “can turn into a competition itself,” as former Deseret News columnist Brad Rock once wrote, arranging a mid-March meeting with Stockton was improbable as an eight-seeded Finals run. I wrote a letter to his Spokane address in November, including my phone number. Three days before Christmas, I got a voicemail from a restricted number: “This is John Stockton,” the voice said. “I’ll try again later today.” He called back the first week of January and agreed to meet. He gave me his email under one condition: that I share it with no one.

We met on the designated day at The Warehouse, a concrete structure near Gonzaga University that Stockton purchased years ago. The surrounding neighborhood has Stockton’s fingerprints all over, too: Down the street is Jack and Dan’s, the bar his father owned for years; next door, a luxury apartment complex that Stockton built with his son and named after his mother-in-law. At the university, of course, Stockton plays the role of Most Famous Alumnus. The Warehouse is something of a passion project — it operates as a community rec center, complete with courts for basketball, volleyball and pickleball and an attached baseball facility. On the north side, Stockton installed an old Delta Center court, still emblazoned with Jazz logos, that he bought from then-Jazz owner Larry H. Miller.

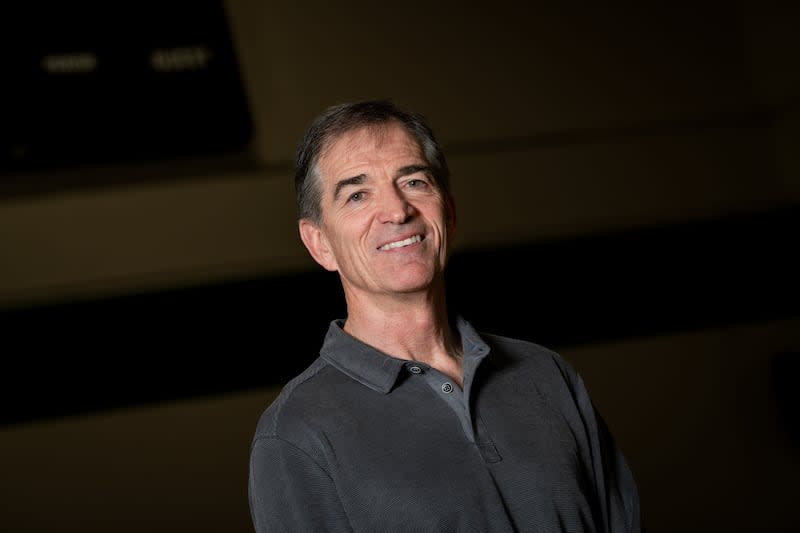

Stockton arrived sporting a flannel jacket and Nike trainers, and after a brief introduction, he set out undertaking janitorial duties: flipping on lights, lowering a basketball hoop, arranging chairs. When he finished, we sat down on the old Jazz hardwood. “So, what do you want to talk about?” he asked.

It didn’t take much to get him talking. The pandemic, Stockton explained, was something of a wake-up call. For an individual who cherished his unassuming, unobstructed life, the lockdowns were repulsive. “This is about freedom,” he told me. “I took classes in high school and college. I know what the Constitution is, I know what the Bill of Rights is. But I’ve never had to care about it.”

Stockton turned to a friend, Robert F. Kennedy Jr., for guidance. Early in the pandemic, Stockton called Kennedy every few weeks to ask about lockdowns or masks or other preventative measures. “John is not someone who’s a troublemaker,” Kennedy told me. “He’s a team player. He’s not a revolutionary. He doesn’t have, like, a rebellious streak. What was driving him was just pure integrity.”

Kennedy spent hours explaining his views on COVID-19 and vaccines. Eventually, as Stockton’s frustration with pandemic mitigation efforts grew, the former Jazz great decided to speak out. “You’re going to bring the wrath down upon you,” Kennedy warned, per Stockton’s recollection. The two-time gold medalist was unfazed.

“For a long time, he just kept his head down,” Jeff Hays, a Utah-based documentary filmmaker, said. “And eventually, he reached the point that he said, ‘this is worth taking a stand on.’”

In early 2021, Hays began working on a documentary about the COVID-19 pandemic. Stockton made a cameo in the second episode of a nine-part series, focusing mostly on the impacts of pandemic-era lockdowns. “This isn’t the virus cheating us of these opportunities; it’s the guys making decisions saying, ‘No, no, we’re too scared; we’re going to shut everything down. Sit in your house and be careful,’” Stockton said in the film. “My kids and grandkids are hearing these things and accepting them as truth when I know by my significant amount of research that it isn’t, and it’s very frustrating.”

That research led Stockton to other conclusions, many of which were disputed by public health officials. He claimed vaccines were not a safe or effective way to protect against the virus. In January 2022, he alleged over 100 professional athletes had been killed by the COVID-19 vaccines. By December of 2022, he asserted it was over 300. He told me it was now “well over 1,000.”

“People say, ‘well, you’re making it up,’” he said. “Well, we’ve got a list.”

When I asked where I could find the list, he explained that someone had sent it to him, and he hadn’t looked at it in some time.

I followed up, asking where I could find it.

He shrugged his shoulders. “I don’t know what to tell you.”

Long before Stockton became a household name in basketball circles — before a street in Salt Lake City and a London bar bore his name — he was an enigma. In high school at Gonzaga Prep, he broke the Spokane city record for points in a game, but it drew only passing interest from colleges. He landed at Gonzaga, a stone’s throw from his childhood home, largely due to convenience. He set the record for career steals there, too. But outside of eastern Washington, few seemed to know who he was.

One notable exception was Jack Gardner, the former University of Utah coach, who worked for the Jazz as a consultant. When he saw Stockton, he instantly saw potential. He got Jazz brass on board; in time, he won over coach Frank Layden. In Stockton, he said, they’d have a star.

His prognosis would prove correct. In Stockton’s rookie season, the Jazz made the playoffs — the franchise’s second-ever postseason appearance. The Jazz would return during each of Stockton’s 18 subsequent seasons. On his way to rewriting NBA record books, Stockton became a fan favorite — clean-cut, soft-spoken, short-shorted. Part of what made him a star was his complete indifference about stardom, said Richard Smith, a longtime Jazz executive. “It wasn’t about having his picture on the front page of the newspaper,” Smith recalled. “It wasn’t about being on the cover of the magazine. It was about the competition of the game itself. ... That’s where he got his joy.”

Stockton, as Layden recalled, fit his coaching style from the start. “We were rather conservative,” Layden said. “We practiced hard. We had certain standards.” And Stockton, a fellow Catholic from a working-class family, didn’t miss a beat. “This was the right place for him at the right time,” Layden said.

But when Stockton first arrived in Salt Lake City, none of that seemed apparent. The Jazz decided to do something special for the 1984 draft. They’d only moved from New Orleans five years earlier, and in an effort to build rapport with the city, they threw an open-door draft-night watch party. “The Jazz were a struggling team, but were starting to build something, slowly but surely,” said Smith, then a part-time college scout and video coordinator. A stage was set up on the Salt Palace floor. Two thousand fans showed up, filling the seats.

When Layden met with reporters shortly before the event began, they tried to pry out a hint of who he’d take with the 16th pick. Layden gave them a smug smile. “You’re going to be surprised, really surprised,” he said. “The person we pick will delight the fans.”

An hour later, when the Jazz were on the clock, Stockton’s name was read. By some accounts, the arena filled with boos. By others, it was a chorus of confused fans, yelling, “Who?”

John Stockton does not claim to be a doctor. He says he does not profit off of his podcast or his media appearances. He professes a deep skepticism of medical and government authority.

Even without formal medical training, though, Stockton’s health is remarkable. Beyond Stockton’s place as a record-holder — he has more career assists and steals than any other basketball player — he maintained incredible stamina. Among Jazz loyalists, the statistics are things of lore: He played until he was 41, when some of his teammates were half his age. Over 19 seasons in the NBA, he missed a total of 22 games. Eighteen of those were due to a knee surgery before the 1997-98 season. Take those away, and he missed four games over 18 years. “He has to be near-death before he’d ever consider missing a game,” former Jazz teammate Mark Eaton once said.

Stockton’s longevity can be attributed to some combination of good genes and an obsession with caring for his body. As each new season approached, Stockton and teammate Karl Malone, who ranks third on the NBA’s all-time scoring list, would compete to see who could arrive to training camp with the lowest body-fat percentage (somewhere between 2 and 3%). At his prime, Stockton’s resting heart rate was 35 beats per minute, about half that of the average adult male.

But the Stockton paradox is his remarkable health while openly rejecting medical orthodoxy. Early in his career, it was less an outright repudiation and more a convenient dismissal — “He didn’t tape his ankles,” recalled Craig Buhler, one of the team chiropractors, with some amusement — but as his body began to show wear, he started searching for alternative methods to care for it.

As a rookie, when Stockton’s more aged teammates lined up at Buhler’s makeshift office in the Salt Palace after practices and games, Stockton scoffed. Buhler worked under head trainer Don Sparks as an unpaid chiropractor. His skills were a thing of legend among Jazz players, but to newcomers like Stockton, it seemed unconventional.

It wasn’t until his second season, after a cortisone shot wore off and some lingering lower back pain returned, that Sparks sent Stockton to see Buhler. Stockton describes the visit in miraculous tones. “Five minutes, and I didn’t have back pain anymore,” Stockton said.

It was the genesis of a long friendship between the two men. Stockton would visit Buhler frequently, and Buhler would work his magic — or, as Buhler styles it, his “advanced muscle integration technique,” a form of chiropractic care that he claims promotes the body’s ability to heal itself. “Nature isn’t stupid,” Buhler would say. During the hours of treatment, the two men would talk about their families, their values and their politics.

In the summer of 1997, Buhler’s help became invaluable. Early in a playoff game against Houston, Stockton got tangled up with Charles Barkley, the league’s hot-headed anti-hero, while setting a screen. The next time Stockton attempted to pin Barkley — setting a routine pin-down screen after a UCLA cut — Barkley lowered his shoulder and rammed Stockton into the floor. The officials whistled a foul. When play resumed, the Jazz ran the same motion, and Barkley delivered an even harder blow.

“I was trying to separate his shoulder or break a rib,” Barkley told the media after the game. The journalists in the room, amused with Barkley’s candor, laughed. Barkley didn’t smile. “I was serious,” Barkley deadpanned.

The next morning, Buhler met Stockton at the team hotel for breakfast. Stockton was hunched over, visibly in pain. “I can’t stand up straight,” he said. Buhler immediately diagnosed it as a disc injury, which could require weeks to heal.

Buhler worked on him for hours, both before and after their flight to Houston, massaging his back and surrounding muscles. The next night, Stockton posted 17 points and 10 assists. Two days later, he scored 22. And two days after that, with the Jazz trailing by 10 points with just over two minutes remaining, Stockton delivered the most consequential postseason performance of his career. He wove through the defense and found a wide-open Bryon Russell for a pair of 3-pointers. On the three subsequent possessions, he blew past his defender, finishing acrobatically at the rim. A double-clutch shot off his right foot. A right-handed finish on the left side. And then, to tie the game, a spread-legged floater over Hakeem Olajuwon’s outstretched fingers.

On the next possession, just after Clyde Drexler spun past Russell and missed a potential game-winner, the ball was back in Stockton’s hands, with the game on the line. By the time a frantic Barkley turned to Stockton — a miscommunication on a switched screen left Barkley double-teaming Malone — the ball was already in the air. The shot gave the Jazz their first-ever NBA Finals appearance. Stockton’s skipping, jumping celebration — two hands in the air, his teammates piling on top of him — showed no sign of back pain.

One day, Buhler offered Stockton an unsolicited suggestion. “You should stop vaccinating your children,” Buhler said. He expressed concerns about their safety and efficacy, and he encouraged Stockton to do his own homework. Buhler didn’t vaccinate his own children. At times, it caused issues at public schools. “But they never had to go to the doctor,” he said, “because we practiced holistic, natural approaches.”

As Buhler kept prodding, Stockton started on his own journey — a process of enlightenment, as he puts it. He started poring over vaccine-skeptical materials and reading books about natural remedies. Before long, he decided that he would no longer get the annual flu shot; not long after, he stopped vaccinating his children, too. “The rose-colored glasses came off on vaccines in general, and therefore medicine in general,” he said.

It was a slow process. “(Buhler’s) suggestions took a while,” Stockton admitted. “Then I witnessed some stuff. Then I saw some more data, and then I witnessed some more stuff.” Shortly after getting his flu shot during the 1989-90 season, a bad bout of influenza leveled him, forcing him to spend a night in a Charlotte hospital. “I could never trace it to (the vaccine),” Stockton admitted. “But I had had the flu shot. Why am I getting the flu?” Later, he told me, one of his children had an allergic reaction to a routine vaccine. Years later, he claims, his father — then late in age — nearly went into sepsis three years in a row after getting a flu shot.

Increasingly, but quietly, Stockton grew adamant that all vaccines — and much of modern medicine — are harmful to our bodies. He began exploring supposed evidence that vaccines cause autism and other developmental diseases in children. He chafed at the ingredients in some vaccines: formaldehyde, thimerosal, aluminum. (The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention dispute that vaccines have any link to the development of autism, and note that those ingredients — while present in some vaccines — are of no safety concern.)

When a mumps outbreak spread through eastern Washington in 2017, Gonzaga officials called Stockton. “Listen, your daughter isn’t vaccinated, and if there’s an outbreak, she’d have to leave campus,” they told him. “She puts other people at risk.” Stockton dug in his heels. “Wait, if they’re all vaccinated, how are they at risk?” An outbreak never hit campus, and the issue was shelved.

But Stockton never went public with his opinions. He wasn’t public about much at all. When it came to his health, he practiced a strict libertarianism, where he would take care of his own body and that of his children, and he’d expect others to do the same. Then the pandemic hit.

Spokane, conveniently, is a mecca of medical expertise. Washington State University’s medical school is housed there, as is one of the University of Washington’s medical campuses, a joint operation with Gonzaga University. In recent years, though, the area’s most recognizable voice on medical issues may be Stockton. “He’s very much a beloved member of the community, and very highly regarded,” said Dr. Guy Palmer, the founding director of the Allen School of Global Health at WSU. But when it comes to vaccines, Palmer and Stockton could not be more different.

“I’m not a physician, so I don’t make actual individual medical recommendations,” Palmer told me at the beginning of our conversation. “I’m a vaccine immunologist, so I understand how vaccines work and how they’re approved.”

Stockton has disputed the efficacy of mRNA immunizations, like the Pfizer and Moderna COVID-19 vaccines. He claims they “aren’t vaccines” for a number of reasons: They do not contain viral material, they “don’t prevent illness” or spread and they followed a short-circuited approval process.

Palmer disputes each of these claims. “People have been working on mRNA vaccines for about 30 years,” he said. “They’re not new.” The idea that COVID-19 vaccines were developed in record time “is not actually correct,” he added — similar vaccines were developed to combat SARS-CoV-1 over a decade ago, so creating a similar mRNA vaccine for SARS-CoV-2 (or COVID-19) was fairly seamless.

“Moving from knowing how the vaccine worked to actually scaling it up and initiating the clinical trials — that was done in record time,” Palmer described. “Not the discovery of how these vaccines worked, but actually the development.” By the time the vaccine was ready for trials, the efficacy studies were performed in record time because there was such a high volume of infections. “When you have a pandemic, it’s pretty easy to see if the vaccine is working or not,” he said. “You have a control group that’s not vaccinated, and a group that is vaccinated. And when you have that much infection pressure, it doesn’t take very long to see the difference.”

The mRNA vaccines do not contain a live virus like traditional vaccines for a reason — instead of injecting a weakened protein antigen into the body which the immune system learns to fight, mRNA vaccines spur a cellular response that leads to the harmless production, and defense against, the virus within the human.

Palmer acknowledged that individuals may have differing reactions to immunizations. “Every vaccine can have adverse effects, there’s no question,” he said. “But most of those are extremely mild.” That’s why individuals should consult a physician before taking a vaccine. But Palmer said he knows of no evidence of widespread fatalities due to the COVID-19 immunizations. “This is the most well-studied vaccine in the history of vaccines. I’m very confident in that statement,” he said. “It is one of the safest vaccines ever produced. But on an individual basis, individuals can have negative reactions.”

Stockton has a heavy dose of mistrust in such perspectives. “I’ve done 25 years of my own personal research,” he said. When I asked if he’s ever made an effort to speak to the experts at the medical schools in his city, he said that “opportunity hasn’t arisen.” When I followed up and asked if he’d thought about going back to school himself — an MD or a Ph.D., perhaps — to have exposure to some of the best materials and best minds on the subject, he seemed to take offense. “I want to touch on the way you asked that question,” he said. “What do you mean, the best information? … You’re saying, just by your tone and your direction, that the only place you can find that is a medical school. I think that’s one of the problems.”

Stockton’s information comes from a number of sources. He isn’t on social media — he uses a flip phone, and when I asked if he has any social media accounts, he asked if Zoom counts. Currently, his favorite book is “Cause Unknown,” written by a Wall Street financier about vaccine-related deaths. He relies on Kennedy and his organization, the Children’s Health Defense, as another source. And, of course, Buhler.

“I ruined him,” Buhler joked, a hint of triumph in his tone. “I take full credit.”

The hours on Buhler’s chiropractic table helped formulate Stockton’s worldview on medicine and health. “I credit to him, frankly, all my longevity,” Stockton said. But in recent years, in a certain turn of tables, Buhler came to Stockton for help. It started on election night in 2020, when Trump lost to Joe Biden. “We followed the election results,” Buhler said. The election, Buhler believes, “was basically stolen.”

In the following weeks, when Trump summoned his followers to Washington for a “big protest” on Jan. 6, Buhler heeded the call. At the last moment, Buhler was unable to attend; his wife and son-in-law went instead, making their way inside the Capitol building and into the Rotunda. “They went up, they looked inside, took a couple of pictures, and then left,” Buhler claims.

In March, the FBI raided their home, Buhler said. His wife was eventually charged on five counts of disorderly conduct, trespassing and other offenses, punishable by up to six months in prison.

The aftermath was swift. She was immediately fired from her job. In an effort to restore his wife’s character, Buhler arranged for a number of close friends to write letters on her behalf. Stockton was one of them.

When I asked Stockton about why he wrote the letter, he was hesitant. “I wasn’t there, so I don’t offer an opinion,” he said. “I would offer an opinion on a good friend, and she’s been a good friend for a long time.”

He chuckled. “This person isn’t a terrorist,” he added.

But what about his view on the Jan. 6 riot — the event which a congressional investigation found to be a premeditated attempt to interfere with an election?

Stockton took a deep breath. For the first time during our interview, he seemed somewhat uncomfortable. “How far do I want to go with this?” he said. “I mean, I wasn’t there.” He seemed to be formulating a response in real time, and began to question to what extent attendees were armed. But he caught himself. “I think I’d probably rather stay away,” he said. “I’m confident in my views on it. I’ll put it that way. But I don’t need to broadcast it.”

The Stockton I met, and the Stockton described to me by a half-dozen of his friends and acquaintances, is this: a good man with concern for his health and his freedom, and a sincere desire to protect both.

He’s a man who quietly invests in his community, rooting for the home team where he once donned a jersey and coaching the neighborhood kids. He still plays pickup on Sundays with a group of locals. Some talk about quiet acts of service, including helping boaters out on Priest Lake in Idaho, where his family vacations.

But this Stockton, two decades removed from his basketball career, now dons an entirely different public persona: that of activist and podcaster, one more eager to dish medical advice than basketball assists. In an age when athletes are encouraged to speak out and dribble, his foray has been met by skepticism. To some, like Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, he makes all professional athletes look like “dumb jocks.”

The day before our interview, news broke on two fronts. The New York Times reported that Kennedy’s top choices for his running mate were Jesse Ventura, the wrestler-turned-Minnesota governor, and Aaron Rodgers, the New York Jets quarterback. (Kennedy, when asked if he ever considered Stockton, hesitated. “We should have.”)

Rodgers and Stockton both endorsed Kennedy around the same time, forming a cohort of current and retired professional athletes vouching for Kennedy’s vaccine-skeptical stances. When I asked Stockton what he thought of the potential VP picks, he was noncommittal. “Listen, I don’t know anything about politics,” he said. “I don’t know whether they’d be good choices or bad choices. But one thing athletics taught me, was that even if you read it, you just kind of wait and see. You’re going to hear a guy’s the greatest player in the world one day, and the next day, he’s the worst.”

Stockton was much more willing to opine on another piece of news. Hours earlier, a local newspaper reported that Stockton was the lead plaintiff on a new lawsuit, filed in federal court, against the Washington attorney general and executive director of the Washington Medical Commission. The lawsuit accuses government officials of violating First Amendment rights by censoring doctors who spoke against “the mainstream Covid narrative.”

“My experience — it’s called bonehead legal education — is the truth is an absolute defense,” Stockton said. “And they don’t even have the truth on their side, let alone freedom of speech.”

The lawsuit’s main complaint follows these lines: The Washington Medical Commission, the body responsible for licensing medical practitioners across the state, adopted a pandemic-era policy that would allow them to discipline medical professionals for spreading “COVID misinformation,” defined as “treatments and recommendations regarding COVID-19 that fall below standard of care as established by medical experts, federal authorities and legitimate medical research.” In the plaintiff’s view, this is a violation of free speech rights.

“Their job should be to do everything they can to promote the health of people in their state, not attack a person’s second opinion,” Stockton explained.

As we talked through the legal arguments, Stockton conceded he’s no expert. “I don’t know that I can speak (to that),” he said. It was less a dismissal, and more an admission that his attorneys — including Kennedy, one of the lawsuit’s lawyers — would handle the legal arguments, and Stockton would stick to the general principles: that he felt like freedom was being violated, and he wanted to be left alone.

This is the Stockton that his teammates and closest friends knew: reserved, unassuming, but deeply driven by his strongly held ideas. His fans just never really knew what those ideas were. “Stocks never wavered one iota from his beliefs,” Karl Malone once said. “He never shared them publicly, so people thought he didn’t have them. He did, and he stayed true to them.”

And so here, the all-time basketball great, is reintroduced to society after a two-decade hiatus — this time not as an athlete, but as an activist, diving into some of the public’s most controversy-laden topics. This isn’t a new Stockton. He’s just decided to openly speak his mind. “I was famous for a reason,” Stockton repeated. “If whatever I have of that fame, to help people see this … maybe that’s my real mission in life, not bouncing a ball.”