The financial crisis changed the bond market forever

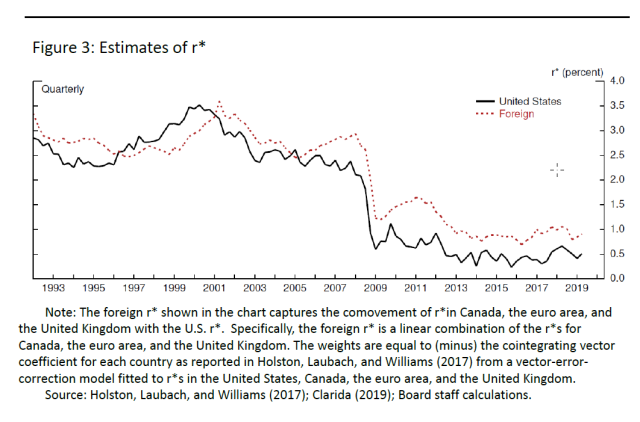

Last week in Zurich, Richard Clarida, vice chairman of the US Federal Reserve bank, made a speech about how monetary policy—the raising and lowering of interest rates—has become more challenging in a low inflation environment. Among the figures and evidence he presented was startling picture of what central bankers call r*.

r* is a calculation of the natural rate of interest, or roughly the short term or risk-free interest rate that would prevail if monetary policy was neutral (not trying to boost or slow the economy). It fell after the financial crisis and stayed low and is beginning to look like what economists call a structural change. Asset prices tend to move around, but sometimes they change permanently, or their natural level changes for a very long time. That r* has stayed so low for more than 10 years suggests a big change.

Falling r*

Although r* doesn’t represent a bond that is directly traded, it is one of the most important interest rates in the economy. First it tells us (and central bankers) if monetary policy is expansionary or not: If they set rates above or below r* they are contracting or juicing the economy. But r* is also the foundation of the bond market. Bond yields are a function of r*, expected inflation, and a premium to compensate investors for bearing the risks involved with holding bonds for longer. A structurally lower r* means lower interest rates on all bonds, and this can have profound implications for the economy.

Why did it change?

The trend is global so whatever changed, it happened to all industrial countries. Economists cite several factors (pdf) including lower and predictable inflation, the consequences of an aging population looking to de-risk its retirement saving, lower productivity because r* is the return on capital (and it is less productive it returns less), and less-than-compelling investment options. But mostly it comes down to supply and demand.

Even before the 2008 crisis there was high demand for safe assets. Developing countries started buying more US and European bonds after the Asian financial crisis in 1997. And in the mid-2000s, US and European financial firms started buying more safe debt too, because of regulations, the need for collateral, and the desire to hedge equity risk. But what changed suddenly in 2008 was the supply of safe assets. Before the crisis, investors bought government bonds and private sector assets including things like mortgage backed securities. After the crisis, the demand for safe assets increased even more as investors became more aware of risk. But after the bottom fell out of the mortgage-backed security market, investors no longer considered many private sector assets safe or desirable. Demand increased just when the supply of high-rated bonds investors considered safe shrank. The safe asset yield, r*, fell and never recovered.

How this changes everything

A lower r* makes it harder for central bankers to conduct monetary policy. Even with negative interest rates there is only so far rates can be cut. If r* is hovering around 7%, there’s lots of scope for cutting rates to boost the economy. Not so much when r* is only 0.5% . The Fed also conducts monetary policy by buying government bonds, and if there’s a shortage of safe assets, expansionary policy only makes any shortage worse.

There are also implications for financial markets. The risk-free rate is the foundation of all financial decisions and appears in most financial models that determine asset prices. It also represents the price of risk. If the risk-free rate is lower, taking less risk becomes expensive and investors either must accept lower returns or take more risk. This is not just for big banks. Lower interest rates make pensions more expensive— and can lead to pension funds to either close their plans or take more risk.

A lower risk-free rate is why many asset managers are rethinking the traditional 60-40 split of stocks-to-bonds they recommended to retail investors. Holding so many low return assets is no longer realistic if workers hope to retire one day. If everyone holds more risky assets, it can impact how they choose to work (they may want more stable jobs or desire more gig work to smooth out shocks), save, and consume. For example, lower risk-free returns could encourage workers to save more and consumer less, to protect against swings in asset prices. A lower risk-free rate mostly means there’s more risk in the economy and that makes everything more unpredictable.

The Fed is not sure if the current environment of high demand and low supply of low risk assets will last forever. There are signs the tide may turn, but it may get worse before it gets better. For now, after the crisis we are living in very low-rate world, and that changes everything.

Sign up for the Quartz Daily Brief, our free daily newsletter with the world’s most important and interesting news.

More stories from Quartz: