Federal-State tensions in fulfilling the ACA’s promises

Nicole Huberfeld from the University of Kentucky explains the relationship between the federal government and the states in the implementation of the Affordable Care Act, and why state cooperation in Medicaid expansion is even more important than the ACA Exchanges for some people.

The Affordable Care Act expresses many goals, but its heart is the desire to create a health insurance home for all Americans.

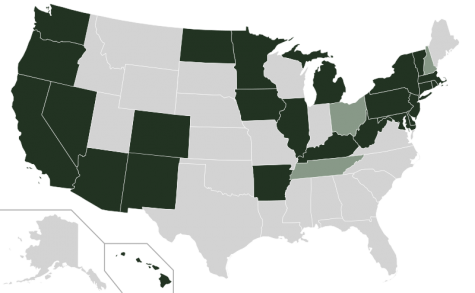

States accepting Medicaid expansion (black), rejecting it (light gray), undecided (dark gray). Wikimedia Commons/Kurykh.

The American health care system historically exists at the pleasure of a number of stakeholders and is not a coherent whole. This lack of system is reflected in the consistent tensions that underlie American health care, most notably federal power versus state power; the collective versus the individual; and the individual versus the state.

In creating near-universal health insurance, the ACA has resolved one of those tensions, individual versus the collective, in favor of the collective. To that end, the ACA eliminated many of the practices health insurers used to cherry pick policyholders, which excluded people who need medical care from their risk pools. In so doing, the ACA represented a federal choice to make all people insurable, whatever their wealth, age, medical history, sex, race, or other distinguishing factor.

Despite the redirection this leveling of the health insurance playing field represents, the ACA did not craft a coherent whole out of the American health care system. Instead, the ACA remodels the pre-existing, unstable healthcare system. In building on the old foundation rather than starting anew, the law retained the historic role of the states in regulating medical matters. To that end, the ACA urged the states to implement two key aspects of its insurance modifications: Health Insurance Exchanges and the expansion of the Medicaid program.

The federal government has the power under the Spending Clause to create a federally run insurance mechanism, but it chose instead to employ cooperative federalism to keep states engaged in health care policymaking. The trouble is that some states have not been cooperating with these central legislative goals.

The Exchanges, or Marketplaces, are an instrument through which qualified private health insurance plans can be purchased by individuals or small businesses.

The states were offered federal funding to create their own state-run Exchanges, which were operative as of October 1, 2013 (last Tuesday). Many states created Exchanges, but many also rejected them as an expression of their distaste for the ACA. Predictably, many of the states that have refused to create their own Exchanges were the same states that challenged the constitutionality of the ACA.

While there is value in dissent, the states that refused to create Exchanges invited more federal power into the state, because rejecting the federal offer for funding to create a state-run Exchange did not halt Exchanges from coming into existence. Instead, the ACA tasked the federal government with operating Exchanges in states that did not create their own.

While expressing a desire to protect their state sovereignty, these states have invited federal authority into their borders. Though the Exchanges at both the state and federal levels have experienced some technical glitches this week, it appears that many people are eager to purchase insurance through them and that they have been successful at doing so. The states that rejected Exchanges have not stopped implementation of the law, but their actions have other notable ramifications.

The Medicaid expansion was designed to catch childless adults under age 65 and below 133 percent of the federal poverty level in Medicaid’s safety net.

As with other modifications to the Medicaid program over the years, the expansion added a new element to the Medicaid Act that states could reject, but they could lose all of their funding if they made that choice.

The day the ACA was signed into law, states challenged the expansion of the Medicaid program as unconstitutionally coercive. They succeeded on this claim in NFIB v. Sebelius, and the Supreme Court rendered the expansion optional for states. Immediately pundits began to question whether the states would participate in the Medicaid expansion.

Though national media tallies make it appear that just over half of the states are participating in the Medicaid expansion, in reality the number is and will be much higher. In almost every state reported as “leaning toward not participating,” and in many states reported as “not participating,” some significant act has occurred to explore implementation of the Medicaid expansion. Some states have special commissions or task forces researching expansion; some state governors have indicated a desire to participate and have included the expansion in the budget; some legislatures have held debate or scheduled it for the next session; and so on. Though some states will not have their Medicaid expansions running by January 1, 2014, it seems very likely that most if not all states will participate in the expansion in the relatively near future.

In the meantime, state non-cooperation will have a direct effect on some of the nation’s poorest citizens. People from 100 percent to 400 percent of the federal poverty level are eligible to receive tax credits for purchasing insurance in the Exchanges.

In states with no expansion, people above 100 percent of the federal poverty level who would have qualified for Medicaid will still be able to obtain insurance through federal subsidies in the Exchanges. But, people who are below 100 percent of the federal poverty level will be too poor for tax-credits and living in states that have not yet expanded their Medicaid programs, therefore they will not be able to enroll in Medicaid either.

These very low income people will not be penalized for failing to carry health insurance, but they will not have health insurance either. These individuals will get caught in a health insurance black hole that exists in part because the Court allowed states to refuse Medicaid expansion and in part because of state resistance to partnering in the implementation of the ACA.

State cooperation in the Medicaid expansion is even more important than state participation in the Exchanges, because many thousands of people may not get the access to health insurance that is the promise of the ACA.

The debate over the meaning of federalism that swirls around political and academic circles will have a direct and important effect on the people who can least afford it.

The good news for them is that Medicaid’s history indicates that all states eventually participate in the program and its amendments, but last week’s implementation of the Exchanges keeps access to medical care through health insurance tantalizingly out of reach.

Nicole Huberfeld is H. Wendell Cherry Professor of Law and Bioethics Associate at the University of Kentucky. Her work has been cited by the Supreme Court and in numerous amicus briefs before the Court. She researches the cross-section of constitutional law and health care law and is currently studying the federalism implications of the ACA’s implementation.

Recent Constitution Daily Stories

Top quotes about 14th Amendment debt-ceiling debate

Looking at the 14th Amendment’s long-forgotten architect

McCutcheon v. Federal Election Commission: The next Citizens United?

For President Obama, winning a short-term debt battle is not enough