Fear, awe and Tecumseh: What was life like in Ohio during the 1806 total solar eclipse?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

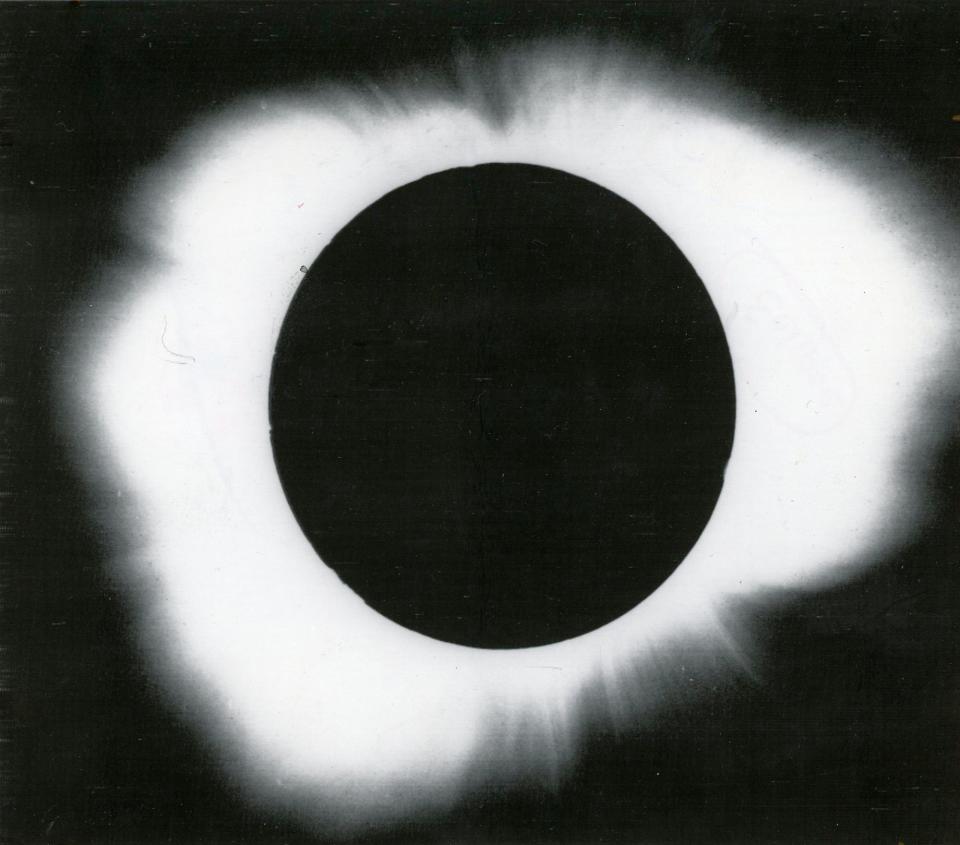

It's been more than two centuries since a total solar eclipse shrouded Ohio in temporal darkness on June 16, 1806. An event that sparked fear and awe. Reverence and superstition. Uproar and enlightenment.

Ohio was in its infancy, having officially become the 17th U.S. state just three years earlier.

Thomas Jefferson was in the fifth year of his presidency. The Lewis and Clark Expedition, after traveling through the Louisiana Purchase and reaching the Pacific Ocean, began its eastward journey back to St. Louis. Construction was recently approved to begin the National Road, the first federal highway. Noah Webster published his inaugural American English dictionary.

Within the decade, Ohio would grow from nearly 46,000 people to more than 230,000 people, according to the U.S. census. And that's a conservative undercount, as that number only included "free whites," said Ben Baughman, a curator at the Ohio History Connection. Columbus wouldn't become the state capital for another decade.

People flocked from eastern states to Ohio, Baughman said, with thriving settlements like Cincinnati and Marietta growing along the Ohio River. A number of indigenous peoples still called Ohio home, including Delawares, Iroquois, Miamis, Senecas, Shawnees and Wyandottes.

Tecumseh's Eclipse

The 1806 solar eclipse would prove especially significant for two Shawnee brothers: Tecumseh and Tenskwatawa.

Tecumseh, the revered Shawnee war chief and political leader, was working to create a confederation of Native American tribes across the continent to resist continued losses of land to increased expansion of settlers into native territory. His younger brother, Tenskwatawa, was widely known as "The Prophet" and a spiritual influence.

Tecumseh did not attend the signing of the Treaty of Greenville in 1795, in which Native tribes ceded most of Ohio to the United States government, because "he didn't have any confidence in it," said Tom O'Grady, an Ohio University astronomy professor and historian.

"He had already fought in a European war. He got along with them, but he didn't want to lose any more land," O'Grady said.

This effort was viewed as a threat to William Henry Harrison. Harrison, who would later be elected as the ninth U.S. president, was currently serving as the governor of the neighboring Indiana Territory.

In a letter written on April 12, 1806, Harrison attempted to discredit Tecumseh and Tenskwatawa by demanding that their followers ask The Prophet to "cause the sun to stand still — the moon to alter its course — the rivers (to) cease to flow — or the dead to rise from their graves. If he does these things you may then believe he has been sent from God."

A mighty ask, but nothing the brothers couldn't work with, O'Grady said.

The story goes that upon hearing the challenge, The Prophet replied that in 50 days, when the sun was at its highest point in the sky, "the Great Spirit take it into her hand and hide it from us" and day would turn to night.

Around 11 a.m. on June 16, the prophecy was fulfilled as a total solar eclipse passed over Ohio.

But how did the brothers know about the impending solar eclipse?

O'Grady said Tecumseh probably learned of the eclipse from settlers on one of his travels, possibly running into a group of "eclipse chasers" who traveled to the area for the phenomenon.

Mark Wagner, director of the Center for Archaeological Investigations at Southern Illinois University Carbondale, wrote in a 2017 article that knowledge of the eclipse was presumably a widespread among those "living along the frontier in the lower Great Lakes region as it was among those living in cities farther east." He surmised that Natives who frequented trading posts, forts and towns likely heard a lot about the eclipse or could read about it in an almanac.

However they learned of it, Harrison wasn't as keen.

"Otherwise, he might not have chosen those words in his challenge," O'Grady said.

Tecumseh used his knowledge to reinforce the role of The Prophet and himself in an unfolding political landscape in this new state, O'Grady said. Harrison never backed down, but local tribes likely stuck with the brothers for a while.

"I can only imagine Tecumseh and his brother earned a lot of street cred that day," O'Grady said.

Who else witnessed the 1806 total solar eclipse?

Although astronomy had been studied well before 1806, sharing that knowledge with those on the frontier posed a greater challenge than to those living in the more populous east coast states.

There were few operating newspapers in Ohio: including The Western Spy and Hamilton Gazette, which published in Cincinnati from 1799 to 1822 and the Freeman’s Journal and Chillicothe Advertiser in Chillicothe, which is still in operation as the Chillicothe Gazette. The first camera wouldn't be invented for another decade, so there were no photos to share either.

The Hampshire Federalist, an early American newspaper in New England, published the account of a Dr. Williams, who witnessed the eclipse in Vermont: "From the beginning to the time of the greatest obscuration, the color and appearance of the sky were gradually changing from an azure blue to a more dark and dusky color, until it bore the aspect and gloom of night. The degrees of darkness was greater than was expected, while so many of the solar rays were still visible."

On the Ohio frontier, others were at work when the eclipse took place. Truman Gilbert Sr., who had recently moved from Connecticut with his wife and eight children, was building a house in Portage County when the eclipse began.

“When Truman Gilbert was raising his house in 1806, and was being assisted by the neighbors, as usual, and some Indians, an eclipse of the sun occurred, which badly frightened the latter,” Robert C. Brown and J.E. Norris wrote in their 1885 edition of “The History of Portage County, Ohio.”

“They left the work, got out their bows and arrows and began firing their arrows up into the heavens in the direction of the slowly darkening sun, to scare off the evil spirit," they wrote.

Others blamed the eclipse for bad luck throughout that year. Fifteen-year-old Christian Cackler had moved to northeast Ohio from Pennsylvania in 1804.

When he wrote his 1874 memoir, “Recollections of an Old Settler: Stories of Kent and Vicinity in Pioneer Times,” Cackler blamed that year’s ruined crops on the eclipse.

“The day of the great eclipse was a beautiful, warm day; we were hoeing corn the second time, with only shirts and pants on, but, after the eclipse was off, the weather was so much colder that we had to put on our vests and coats to work in,” Cackler wrote. “There were frosts every month that summer; no corn got ripe, and the next spring we had to send to the Ohio River for seed corn to plant.”

Ohioans won't have to wait quite as long to experience the next total solar eclipse. Just a quick 76 years.

Enough time for our grandchildren to ask: "What was life like during the eclipse of 2024?"

Sheridan Hendrix is a higher education reporter for The Columbus Dispatch. Sign up for Extra Credit, her education newsletter, here.

shendrix@dispatch.com

@sheridan120

This article originally appeared on The Columbus Dispatch: How Tecumseh used the 1806 total eclipse in Ohio to his advantage