Young father imprisoned in Iran: An American dream turned nightmare

The last memory Hua Qu (pronounced “chu”) has of her family together was during a trip to see the cherry blossoms in Washington, D.C. Under a canopy of pink petals, her husband, Xiyue (pronounced “she-yeh”), grabbed their toddler son, spinning him around in a dizzying twirl that lifted Shao Fan’s little feet right off the ground. The boy giggled as his mom captured a video of the happy moment on her iPhone. It was a short and sweet family excursion in the spring of 2016, before Xiyue Wang planned to leave his young family for Iran.

A fourth-year doctoral student at Princeton University and a Chinese-born naturalized American citizen, Wang had been invited to study Farsi by a foreign language institute in Tehran. He had also been granted permission by Iran’s Foreign Ministry to conduct research for his dissertation on late 19th and 20th century Eurasian history.

“He was a history nerd,” said a former student of his, Patricia Crawford, in a video compiled by the Free Xiyue Wang campaign. “I’ve never seen him without a book.”

Before Princeton, he’d been a student at the University of Washington and Harvard University. So much did he value the academic opportunities he’d been given in America, he gave up his Chinese citizenship in 2009 to become a U.S. citizen.

According to Qu, her husband thought nothing of the risks of being an American academic studying in Iran. And even when, on the week he was due to return to the U.S., Iranian authorities suddenly seized his passport and laptop, he thought it was a routine security check that would quickly clear him to return to his family. Three weeks later, Qu says, Wang disappeared. Princeton University officials retained an Iranian lawyer who eventually found Wang in Tehran’s Evin Prison.

It was August 2016. That summer, presidential candidate Donald Trump was vociferously denouncing the nuclear agreement the U.S. and four other major powers had reached with Iran, calling the deal “an embarrassment” for not doing enough to rein in Iran’s nuclear ambitions or its other destabilizing activities in the region. Trump wasn’t the only one who hated the pact, formally known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA). So did hard-liners in Iran, and it is those hard-liners who run Evin prison.

Experts on Iranian politics believe those factions are behind the continued detentions of Americans held in Iran. Revolutionary Guard members loyal to the Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei not only control the security forces, but also the courts. Imprisoning Americans is their way of “exercising their power to undermine the JCPOA,” according to Hadi Ghaemi, the executive director of the Center for Human Rights in Iran, a New York-based advocacy group. In other words, the Americans held in detention are not only bargaining chips, but part of an internal Iranian struggle for control over the country’s foreign policy. The hard-liners are competing for power with elected officials such as President Hassan Rouhani, a relative moderate who negotiated the JCPOA, along with Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif.

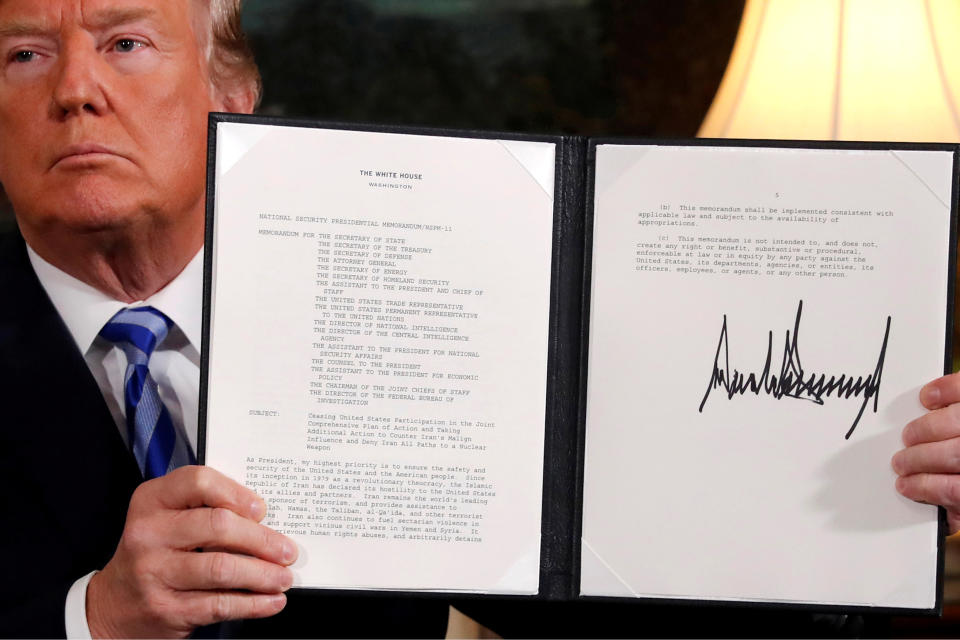

Now that President Trump has followed through with his campaign promise to withdraw from the deal, the prospect that Wang and at least four other Americans held in Iran will be released soon seems even more remote.

“The situation has gotten worse because the tensions within Iran over how to interact with the outside world are dividing the country,” said Ghaemi. “People who end up caught up in detention are paying a much heavier price because the stakes are much higher now.”

Four dual Iranian-American citizens are also being held in Iran — Siamak Namazi, a businessman; his 82-year old father, Baquer Namazi, a former UNICEF official; Karan Vafadari, an art dealer; and Gholamreza Shahini, who was visiting relatives when he was detained. All five were arrested after the nuclear agreement was implemented. But the reasons may have been more than just political.

While the Obama administration was agreeing to the terms of the Iran deal in 2015, it was also negotiating a controversial prisoner exchange and large cash payment to Iran. On the day the U.N. lifted sanctions, Iran released four Iranian-Americans, including Washington Post reporter Jason Rezaian, in exchange for seven Iranians that had been detained in the U.S. The U.S. also gave Iran $400 million. While Trump’s description of the payment as “ransom” was inaccurate (the funds were previously owed to Iran and were frozen after 1979), some critics of the arrangement say the cash payout had the same effect — it made arresting Americans in Iran potentially profitable, and may have led to the spate of detentions in Iran since.

“A large amount of cash was shipped directly to the Revolutionary Guard for the release of those dual nationals,” said Ghaemi. “And that really made the Revolutionary Guard believe that these actions can bring them financial benefit of huge sums.”

Over the years, cases of detained Americans in Iran have followed a familiar pattern, and Wang was no different — vague charges of espionage or state subversion, a period of solitary confinement and endless interrogations in Evin’s infamous Ward 209 followed by secret trials, convictions and arbitrary sentences issued with scant evidence.

Wang went through all of that from August 2016 to July 2017 before the American public even knew of his case. Hua, Princeton University officials and the State Department quietly worked on his release. But after his conviction last July, reports started coming out of Iran about Wang. And last fall, a hard-line Iran state television station, IRIB2, broadcast a video report about Wang’s imprisonment. In the video, Wang is interviewed talking innocuously about his research, but the narrator depicts the scholar as a spy and claims he “infiltrated” Iran’s national archives.

Wang received a 10-year sentence on charges related to espionage, and his appeal was denied.

In a May 10 interview with “CBS This Morning,” Vice President Mike Pence suggested “the possibility of a new deal” with Iran, which “may create opportunities for not only addressing the issue of Americans that are detained in Iran, but also checking the extraordinary malign influence and support for terrorism that Iran continues to propagate across the region.”

But with European allies so far remaining in the Iran deal, it’s not clear how to reach a “new deal.” U.S. and Iranian relations have deteriorated since Trump took office, as has trust between the U.S. and some of its traditional allies.

“Regardless of Trump’s actions on the nuclear deal or how he plans to implement his decision, it is urgent that the U.S. government develop a humanitarian channel for talking with the Iranians about the fate of these prisoners,” said Ghaemi.

In a statement to Yahoo News, a State Department official said:

“The safety and security of U.S. citizens remains a top priority. We call for the immediate release of all U.S. citizens unjustly detained and missing in Iran …The U.S. government raises with Iran at every opportunity the cases of U.S. citizens missing and unjustly detained in Iran. We will continue to do so until their cases are resolved.”

Visiting Hua Qu in her small apartment near the Princeton University campus, it is clear that two years without her husband have taken their toll. She had given up a lot to relocate from Beijing to support Wang’s academic career, and for two years she’s had to raise their son by herself while searching for any news out of the region that might affect Wang’s case, and anxiously awaiting updates from the State Department.

At a recent Princeton rally calling for her husband’s release, Qu pleaded with Trump to meet with her so she could explain that her husband “is a good man and a proud American.” She hoped that with the recent release of three Americans from North Korean custody, Trump might achieve a similar breakthrough with the Iranian authorities imprisoning Wang.

“I miss him terribly,” she said, with the studied composure that comes from two years of fighting back tears. “As time goes by, I fear more and more for his safety.”

Read more from Yahoo News: