Gunman's family told deputy before Maine's deadliest shooting that they hadn't removed his weapons

AUGUSTA, Maine (AP) — Police have said repeatedly in the aftermath of Maine’s deadliest shooting that officers thought the gunman's family had been taking his weapons away.

Testifying before an investigative committee on Thursday, the gunman’s sister-in-law suggested that law enforcement officers should have known this wasn’t true, because she and her husband, Ryan Card, told a deputy on the phone a month before Robert Card killed 18 people that he still had access to weapons, despite his deteriorating mental health.

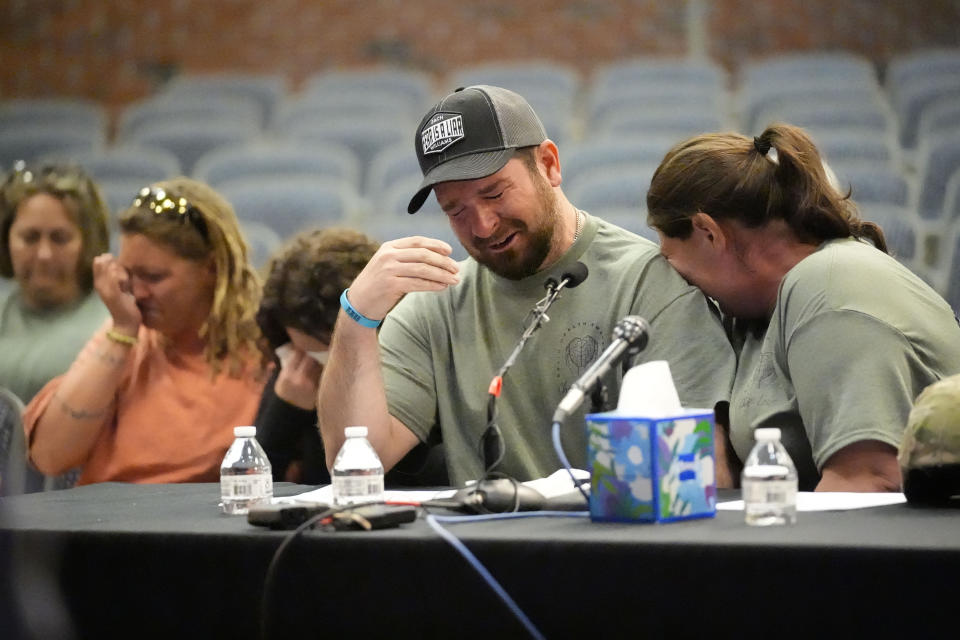

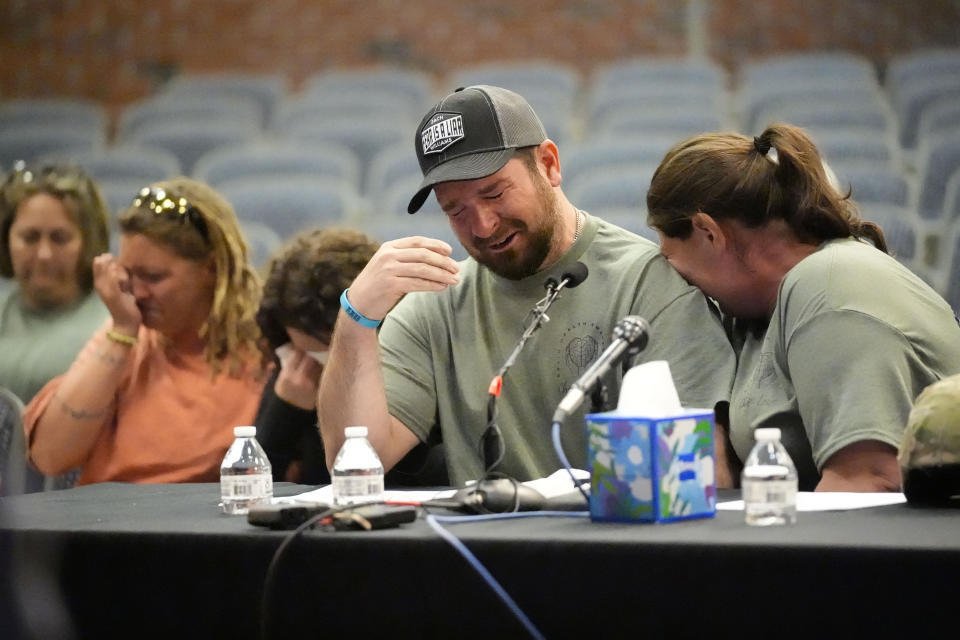

“We will always blame ourselves. My husband will always blame himself, even though it shouldn’t be blamed on him," Katie Card said. "He will always blame himself. I will always ... I know in my head we shouldn’t ... but we will always.”

The revelation came during the first public testimony from Card’s relatives. One after another spoke of frustrating attempts to get help, and offered emotional apologies to the victims and their family members.

The independent commission appointed by the governor already heard from police, victims and their families, and other Army reservists about the deadliest shooting in Maine history. Card, 40, killed himself after opening fire with an assault rifle inside a bowling alley and a bar and grill in Lewiston in October.

In the aftermath, the legislature passed new gun laws for Maine, a state with a long tradition of firearms ownership. Among other things, they bolstered the state’s “yellow flag” law, criminalized the transfer of guns to prohibited people and expanded funding for mental health crisis care.

Card’s family had kept a low profile after the tragedy, other than releasing a statement in March expressing deep sorrow and disclosing an analysis of Card’s brain tissue that showed evidence of traumatic brain injuries. Card had trained others in the use of hand grenades, and the family blamed the repeated blasts for his mental decline.

The commission issued an interim report in March saying law enforcement should have seized Card’s guns and put him in protective custody based on the warnings from family and reservists, using the existing yellow flag law. A full report is due this summer.

Police testified that the family had agreed to remove Card’s guns, but the commission said leaving such a task to them “was an abdication of law enforcement’s responsibility.”

Katie Card said Thursday that a deputy had applied pressure — to his brother Ryan in particular — to offer assurances that the guns were taken away so that the deputy could wrap up his investigation ahead of a two-week vacation. She said she and her husband “both expressed that day (to the deputy) and multiple times after that we had been unsuccessful.”

She said she and Ryan Card, whom she described as a retired Army ranger who is disabled after deployments to Iraq and Afghanistan, remain wracked with guilt even though it was unfair for law enforcement to make estranged family members responsible for removing Card’s guns.

Other relatives also vented their frustrations, blaming the military, law enforcement and media coverage. James Herling, husband of the gunman’s sister, singled out the Army Reserves for declining to answer the phone or return their calls as they sought help. Card’s ex-wife, Cara Lamb, accused police of ignoring or dismissing warning signs.

Nicole Herling, the gunman's sister, said military personnel deserve better protections: “It’s unjust to continue training with explosions and sonic booms until there are protective gear and standards ensuring the safety of all of our soldier’s brains.”

“This is not an excuse for the behavior or acts that Robbie committed,” James Herling testified. “It was a wrongful act of evil. My brother-in-law was not this man. His brain was hijacked.”

An Army spokesperson said Thursday that the Army “is committed to understanding how brain health is affected and to implementing evidence-based risk mitigation and treatment” and that the Army this year is conducting cognitive assessments of trainees that can be repeated to identify changes.

As for the mass shooting, the Army Reserves and the Army inspector general are conducting separate investigations into the events and “more details may become available once the investigation is complete.”

Lamb said their teenage son was so concerned about Card’s growing paranoia and access to guns that she shared his worries with a school resource officer in May 2023. This should’ve been a “flashing sign that we have a problem here,” she said.

Fellow Army reservists witnessed Card’s deterioration, to the point that he was hospitalized for two weeks during training last summer. One reservist, Sean Hodgson, told superiors Sept. 15: “I believe he’s going to snap and do a mass shooting.”

Lamb, for her part, said she herself encouraged officers not to confront her ex-husband for fear of escalation, and harm to her son’s relationship with his father, but now questions that approach.

“I keep wondering if the right thing to do would’ve been to say, ‘Damn it all, damn everyone’s feelings and repercussions,’ and go scream at the police — ‘What do we have to do?!’” she testified.

___

This story was first published on May 16, 2024. It was updated on May 17, 2024 to include a more complete quote from Katie Card’s testimony.

___

Sharp reported from Portland, Maine.