Famed explorer wrote a poignant letter to his wife before dying on Mount Everest

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

George Mallory wanted to be the first Westerner to summit Mount Everest in the 1920s. He didn’t make it.

His final letters survived, however, and have now been digitized and put online for public viewing by Cambridge University 100 years after his death.

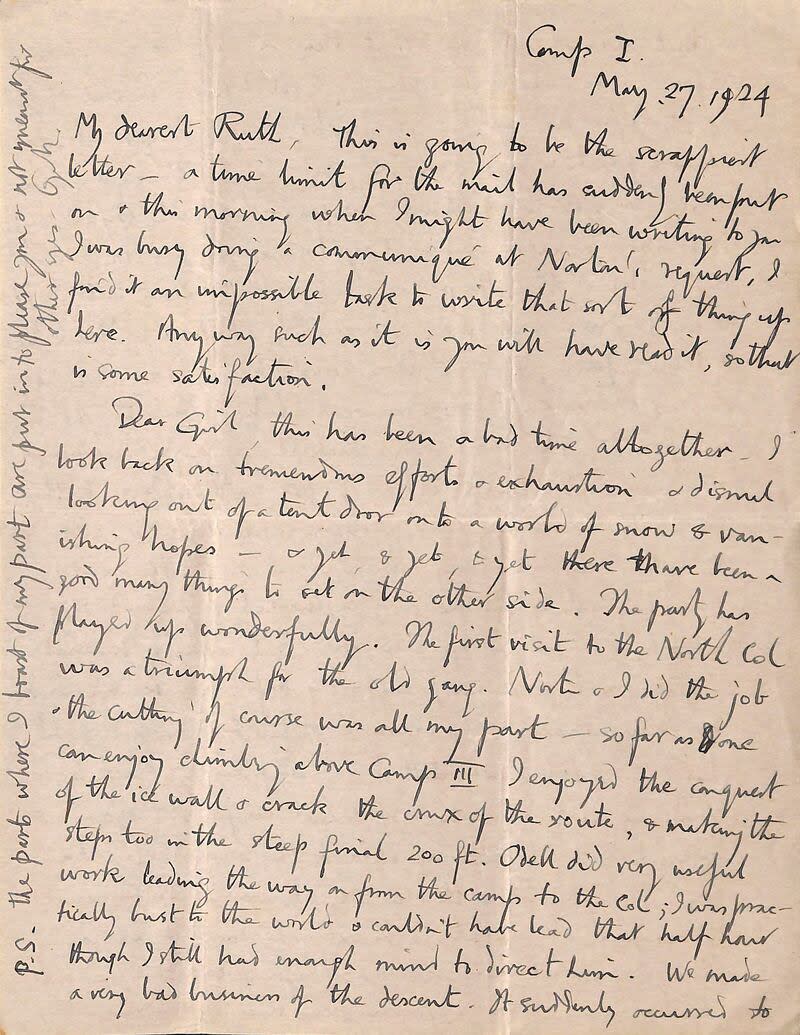

The bulk of the correspondence included in the online archive consists of letters from Mallory to his wife, Ruth, from the time of their engagement and marriage in 1914 until his death on Everest in 1924. In his final letter to Ruth, on May 27, 1924 — less than a month before he died — Mallory detailed the many mishaps that had befallen their group, including knots not holding, deadly crevasses and a nasty cough that he described as “fit to tear one’s guts.”

He began the final letter he sent by saying, “Dear Girl, this has been a bad time altogether.” He ended the letter by saying he estimated the expedition’s odds of success as “50 to 1 against us.”

The letters, according to the Cambridge site, cover some fascinating topics, including:

His first reconnaissance mission to Everest in 1921. There were no existing records or maps, it was uncharted and this was the mission to see if it was even possible to get to the base of Everest.

His second mission to scope out Everest. This mission ended in disaster when eight Sherpas were swept off the mountain and killed in an avalanche. Mallory blamed himself for this tragic accident in his letters.

His service in World War I, including his eyewitness accounts of being in the Artillery during the Battle of the Somme.

Letters from his 1923 visit to the U.S. in the middle of prohibition, visiting speakeasies, asking for milk and being served whiskey through a secret hatch.

Early life

George was born in 1886 in Mobberley, England, to a reverend and his wife. As a young child growing up around various churches, Mallory took to climbing their stone walls.

“He climbed everything that it was at all possible to climb,” his sister recalled, according to a 1999 article in The New York Times. “I learnt very early that it was fatal to tell him that any tree was impossible for him to get up.”

By the 1890s, Mallory was sent to various boarding schools, where he excelled in sports and mathematics. While attending a school in Winchester, Mallory met Graham Irving, a member of the Alpine Club. Through this connection, Mallory experienced his first climbing trip in the Alps at age 18. From this point onwards, the young Mallory was taught to climb properly, and they called their little climbing group the Winchester Ice Club.

It was in early 1909 that Mallory first met the experienced mountaineer Geoffrey Winthrop Young. “Although a decade older than Mallory, Young was to become a lifelong friend and climbing mentor to the young undergraduate, and within weeks of meeting they were climbing together in Wales. It was during these meets at Pen-y-Pass that Mallory was introduced to some of the great pioneers of mountaineering, many already in their middle age. Among them was Oscar Eckenstein, who had twice been to the Karakorams, the first time in 1892 with the great English Himalayan explorer Martin Conway. Another climbing partner was Percy Farrar, who had 17 seasons of Alpine experience. He was later to become president of the Alpine Club, and it was Farrar who proposed that Mallory be included on the first expedition to Everest. Clearly, Mallory was beginning to get himself known in very influential circles.”

He married Ruth Turner in 1914 and they had three children together. He served in France in World War I, but once he was invited to join the British Mount Everest reconnaissance expedition, conquering Everest became a singular goal in his life. Once, when a reporter asked him why he was so focused on summiting Everest, he purportedly said, “Because it’s there.”

The letters to Mallory from his wife Ruth are a major source of women’s social history, covering a wide variety of topics about her life as a woman living through World War I, according to the archival site.

Magdalene College archivist, Katy Green, said: “It has been a real pleasure to work with these letters.

“Whether it’s George’s wife Ruth writing about how she was posting him plum cakes and a grapefruit to the trenches — he said the grapefruit wasn’t ripe enough — or whether it’s his poignant last letter where he says the chances of scaling Everest are ‘50-to-one against us’, they offer a fascinating insight into the life of this famous Magdalene alumnus.”

Last day

He and his climbing companion Andrew Irvine were last seen alive on June 8, 1924, and were said to be going strong some 900 feet below the summit. Mallory’s body was discovered in 1999, more than 2,000 feet below the top and with injuries consistent with a fall of some distance. Irvine’s body has never been found. There were three letters wrapped in a handkerchief and tucked in a pocket on Mallory’s body that are also included in the online archive.

It remains a mystery whether Mallory and Irvine actually reached the summit, although they may have. A group of mountaineers who tried in 2007 to reconstruct Mallory’s ascent were unable to determine if the pair made it to the top.

“I still believe the possibility is there they made it to the top, but it is very unlikely,” said Conrad Anker, who participated in a documentary recreating the climb and who had discovered Mallory’s body in 1999.

Nearly three more decades would pass before Sir Edmund Hillary and his Sherpa guide Tenzing Norgay became the first to officially summit the mountain in 1953.