Faces of Death: How the 'gore porn' sensation became the original viral video and gripped the world

Mary Whitehouse has a lot to answer for.

Whitehouse, who attempted to police the nation’s morals in the 1980s under the guise of the National Viewers' and Listeners' Association (Nvala), the body she ran, has become a figure of hatred among many for her attempts to spoil fun. Sex, drugs, swearing and violence were all forbidden in Whitehouse’s world, and the 1978 horror film Faces of Death was absolute anathema to her.

Faces of Death was one of the famed “video nasties” – questionable content that had spread like a virus throughout the new video rental stores that had popped up on high streets across the world as a result of the shiny VCRs that sat under many household televisions. For the first time ever, movie watching wasn’t limited to a big screen cinema.

Faces of Death had this legend about it. It was this forbidden thing. People were talking about it and how it was all real; you got to see people actually killed on screen

Michael Felsher

In the comfort of their own homes, people could watch whatever they chose – and people’s personal tastes were quite often depraved.

Horror films – particularly a semi-realistic documentary subgenre called mondo – had been popular in the 1960s and throughout the 1970s, but, says Mark Goodall, the head of film and media at the University of Bradford, “the audience had to seek these things out. Most of the mondo films were shown in less salubrious cinemas up and down the country.”

Suddenly, the home video revolution meant that people could indulge their violent side at home.

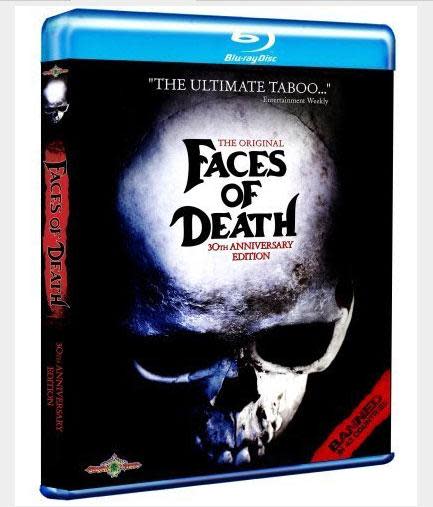

“I’ve always had an interest in horror films,” explains Michael Felsher, the owner-operator of Red Shirt Pictures, a Detroit, Michigan-based production company which helped produce a 2008 documentary for a special Blu-ray and DVD re-release of Faces of Death on its 30th anniversary.

Buoyed by the new world of video rental stores, Felsher’s VCR would gobble up every tape he could get his hand on it. At the junior high school where he studied, there was one tape that people couldn’t stop talking about.

“Faces of Death had this legend about it,” he says. “It was this forbidden thing. People were talking about it and how it was all real; you got to see people actually killed on screen.”

It was a conversation happening in school yards and workplaces across the world in the late 1970s and early 1980s – a prototypical viral video, gaining popularity by word of mouth and an illicit tinge. “It had an underground currency,” says Goodall. “It was sought out by horror fans.”

In the UK in particular, the underground movement that gained pace behind Faces of Death tied in with the burgeoning punk subculture. “People who were looking for extreme films, art house films, naturally gravitate towards Faces of Death. It has this subcultural crossover,” explains Goodall.

From the box art – depicting a huge skull, and with warnings about the graphic content contained within – to the odd mix of violent, hyper-realistic scenes, the 104-minute video quickly gained a name for itself. “It developed this reputation of almost a dare,” says Felsher. “‘Can you watch this?’ That’s what really propelled it.”

The film’s distributor, Gorgon Video, which was created solely to distribute the movie, played up to the forbidden, dark, underground nature of its content. “It was the legend of Faces of Death,” says Felsher. “It inherently had this aura of mystery. It’s the forbidden fruit. The more you’re told you don’t want to watch this… you do.”

Looking back, the film is hokey and of its time. A doctor, “Dr Francis B Gröss”, hosts the production, which shows a number of ways to die, interspersed with other violent scenes, including dogs fighting to the death and the aftermath of horrific accidents. But in the late 1970s, it was revolutionary.

“Faces of Death came at a crossroads when what had been a fairly shocking but colourful and quite nicely put together style of documentary film flipped into being more nasty and unpleasant,” explains Goodall, who interviewed English novelist JG Ballard for his book on mondo films, Sweet and Savage, after finding out Ballard was a fan of the genre.

“He told me what he thought was interesting about them was that they blurred fact and fiction,” says Goodall. “Audiences weren’t really sure – they suspected some of it was fake but went with it and knew they were being co-opted into this slightly manipulative form of film making.”

That sense of a blurred line between fact and fiction has its parallels today, in a time when we’re bombarded with news – both fake and real – with little way of unpicking what’s what. “I think you can trace that back to these films,” says Goodall.

Ballard even coined a phrase for the type of scenes that Faces of Death presented: “the horrors of the real.”

Rather than the traditional tropes of horror films that had typified the genre – of werewolves howling at the moon, vampires camping it up behind their cape and cowering from the sunshine and rictus-jointed monsters lumbering around shaky sets – this new era of film, starting with Faces of Death, presented situations that were all too real to us in a mockumentary style. In one scene you see a man jumping out a window; another involves monkey brains and a restaurant.

“The response they encourage in the viewer is the same as horror: recoiling from something, or a fear that this could happen to you,” says Goodall.

In some cases, it had happened to someone. Faces of Death gained its reputation at the time because people told their friends about this horrific film they’d seen that was a compilation of real life gore porn. (One scene, in which a cult member is sacrificed, ended up being passed around tape trading circles, the quality degraded so much that it ended up in the hands of the FBI, who had to investigate it as it had lost its original tie to Faces of Death.)

In fact, the producers never professed that the film’s violence was real, but people simply believed it. And actually, some of the scenes do show moments of extreme, real violence.

Estimates vary depending on who you ask, but somewhere around a third of the footage contained within the film is real.

One memorable scene shows a man’s body lying dead on a beach. “That’s all real, but it happened by accident,” recalls Felsher, who interviewed several people involved in the production for his documentary.

“They were down there filming something else but they got a report of a body on the beach and happened to be there to film it,” he says. “It was some guy who got high on LSD and had fallen into the water and drowned.”

Other scenes included “found” footage. The American film makers called up local news stations, asking if they had any unused footage of accidents or murder scenes that they’d filmed but weren’t suitable for broadcast on television. Some stations obliged.

But how did Faces of Death come about? How did the American film makers set about shooting odd scenes that combined with real life footage of horrific accidents?

A Japanese company commissioned a group of American film makers to produce an assignment. “The people behind it were more into nature footage, National Geographic-style programming,” explains Felsher. “The Japanese company wanted a hardcore death thing, and hired the nature documentary people because they felt that the subject wasn’t so far off, they could take footage and manipulate it in a way they wanted.”

The director, who Felsher interviewed and still refuses to release his real name (he uses the pseudonym Conan LeCilaire), came from a well-known family in the world of nature documentaries. Though Felsher believes LeCilaire “wasn’t embarrassed by or ashamed of it, he didn’t want to become known as the Faces of Death guy”, and so didn’t put his real name to the film.

It also, on the face of it, wasn't a risk. A low-budget movie (the entire production cost an estimated $450,000) that was quickly decried as tasteless, if it didn’t capture the imagination, it wouldn’t be much of a loss.

The Japanese company believed they could find an audience for this gore porn.

“It was huge in Japan,” says Goodall, and followed in the footsteps of other mondo movies such as 1975’s Last Cry of the Savannah, an Italian-made movie which was more popular at the Japanese box office that year than a newly released film by a young director called Steven Spielberg: Jaws. It also inspired other gross-out films that appeared at least to be anchored in reality, including the controversial Japanese series of Guinea Pig films.

The company just didn’t realise that they’d find such a big audience – and in all four corners of the world. “It was the first movie that really hit the big time in America in terms of capturing that particular generation’s attention,” says Felsher. “It tapped into an American experience. It wasn’t taking place in Africa or some other foreign land.”

The film ended up earning more than $35 million at the box office and spawned many sequels, but has had a longer-lasting legacy than the riches it made. Faces of Death has now become bigger than the film itself: it has become shorthand for a particular type of film, a cinematic approach to death, showing graphic, hardcore footage.

But then again, there’s still an audience seeking out the unbridled, real-life violence that Faces of Death purported to provide. “That hasn’t gone away,” says Goodall. People who watch Isis videos now, it’s the same thing. It’s like a horror. They’re even choreographed to be like a horror film, the way they’re shot, edited, and music added. That’s where they do connect with anxieties and play to society.”

Social media and the prevalence of sites such as LiveLeak, which hosts footage many other sites find too distasteful, is perhaps what dates Faces of Death the most.

“Now, it’s maybe an artefact of its time,” says Felsher. “We’ve gotten much more used to the way violence is depicted thanks to the internet.

“Faces of Death almost plays as an old, corny newsreel now. It doesn’t have the same shock effect. You can see the film making techniques in it now, because we’re so used to accidents, violence, films and murder captured in real time on iPhones without any context. People look at it now and say it’s interesting this was considered so taboo back then.”

But for those who first encountered its jumpy, fuzzy footage in a darkened room as a child – or simply heard about its reputation, too scared to ever take the plunge – Faces of Death still holds an aura that lives on, even if the quality of the film itself doesn’t.