Devastating snowstorm that hit DC a century ago still stands as the city's worst ever

|

For a major metropolitan area on the East Coast of the United States, it's expected that Washington, D.C., will face the same dogged cold, wintry days from year to year. The nation's capital typically sees on average 5 inches of snow in January and reaches a seasonal average of 13.7 inches. Hardly a harsh winter.

But that doesn't mean blockbuster snowstorms never descend on the city -- just turn to three long January days back in 1922.

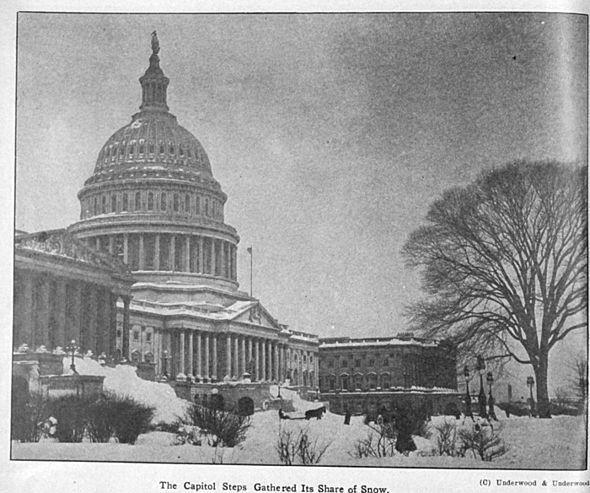

More than a century ago, a monster winter storm brought snowfall rates of 1-2 inches per hour in some instances, burying Washington, D.C., beneath a layer of snow 28 inches deep in late January of that year, an amount that still stands as one of the worst snowstorms to hit the nation's capital.

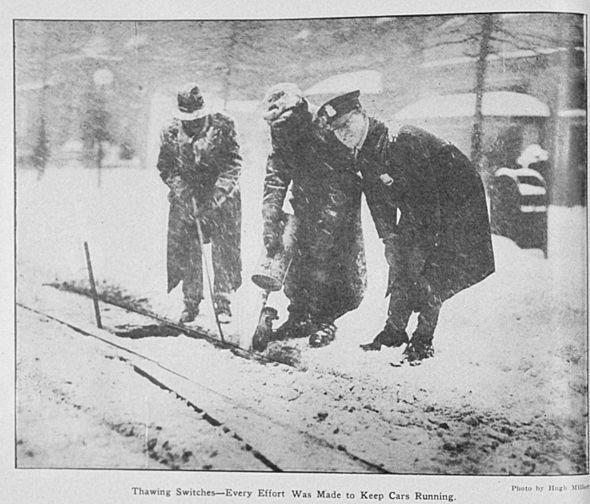

During the span of the storm - from Jan. 27 to Jan. 29 - the heavy snowfall shut down all forms of travel in the city, forcing residents to get to work on foot by trudging through knee-deep snow.

|

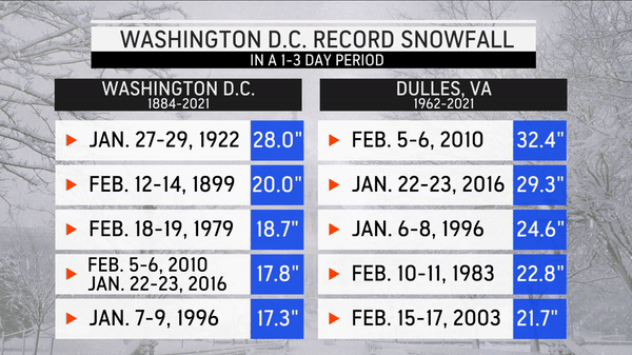

"As of today, this still stands as the greatest snowstorm on record for Washington, D.C.," AccuWeather Meteorologist Carl Erickson said.

The blizzard set a record for the heaviest snowfall in 24 hours after some 21 inches piled up over that period at what was then known as Washington National Airport. Congress renamed the airport, which is located about 4 miles outside Washington, D.C., in 1998 in honor of former President Ronald Reagan.

Many people, however, may be wondering where the so-called "Snowmageddon" of 2010 ranks, given that it dumped 32.4 inches of snow on Dulles International Airport. Well, its impressive snow total doesn't eclipse the 1922 Knickerbocker Storm and the reason has to do with the old real estate adage: location, location, location.

The snowfall totals for the two storms were measured in different places, a critical factor. "The biggest single snowstorm for the immediate D.C. area was the Knickerbocker Storm," Dan Hofmann, a meteorologist stationed in the National Weather Service office in Washington, D.C., told AccuWeather. Dulles International Airport in northern Virginia didn't open until 1962, so it "didn't have records back then," Hofmann added, meaning that for Dulles, located about 30 miles west of Reagan National Airport, the "biggest snowstorm was in 2010."

|

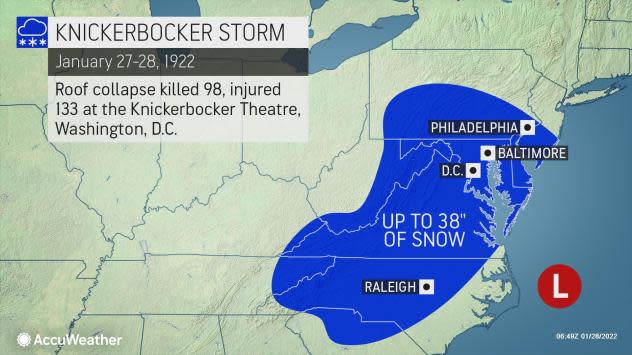

The Knickerbocker Storm took its name from the deadly impact the snow had on the Knickerbocker Theatre. About 400 patrons were watching a movie, Get-Rich-Quick Wallingford, around 9 p.m. when the ceiling caved in and 98 people were killed along with 133 injured on Jan. 28, 1922.

"The weight of the snow was too heavy for the flat roof of the Knickerbocker Theatre to handle. The drifting of snow likely led to an uneven distribution of weight that added to the devastating roof collapse," Erickson said.

The theater was viewed as one of the most fashionable cinemas in its day. But an investigation revealed that the roof beams were inserted only two inches into the walls instead of the eight inches required at the time. After the roof collapse at the Knickerbocker, a stricter building code was established for all theaters in the District of Columbia, requiring the use of better steel beams and more stable supports be used in construction going forward, according to the DC Historic Preservation Office.

Even bigger snow totals than what was measured at the airport were recorded in the area surrounding the nation's capital. An area near the Washington, D.C.-Maryland border, Rock Creek Park, was blanketed in 33 inches of snow from the storm.

Richmond, Virginia, received upwards of 19 inches, and railroads were reportedly immobilized by 36 inches of snow in some locations between Philadelphia and Washington, D.C.

|

Snowdrifts of up to 16 feet high were seen in areas due to the storm's strong winds.

"Snow from the storm fell from interior North Carolina to Connecticut, but by far, the worst of the storm and the heaviest snow fell over Virginia and eastern Maryland," AccuWeather Meteorologist Bob Larson said.

|

"At the time of the storm, printed newspapers were still the primary source for most people of news as it happened," Joel Wurl, the former deputy director of the Division of Preservation and Access at the National Endowment for the Humanities, told AccuWeather in an interview. "I think partly because of that, the articles often tended to be quite dramatic in attempting to capture not only factual information but the emotional content of events."

Wurl authored an article about the 1922 blizzard that goes in-depth about old news stories covering the weather event for Chronicling America.

"I think it's fascinating to read the language journalists used to try to convey the prevailing sentiments of tragedy and shock. I also found it interesting to see how the papers were used as a means of seeking contact with families of victims," Wurl said.

Some examples of the media coverage Wurl points to are below, beginning with this passage from The Tulsa Daily World's Sunday edition that was published on Jan. 29, 1922:

"No warning was given as the walls crashed. The roof breaking in on the heads of the audience with a noise like thunder and crushing seats and occupants as it fell. It was more than an hour before the rescuers using gas torches to cut through the accumulated mass of steel and concrete reached the section where it was believed most of the dead and injured were," the paper reported.

The story continued, noting some of the prominent people wounded in the calamity. "Among the injured were Senator Smith of South Carolina, who was only slightly hurt and Representative Smithwick of Florida was painfully cut about the head and chest but was not seriously hurt."

|

"Every theater in this city, including both motion picture houses and playhouses," the news story went on, "was ordered to close tonight, not to re-open until building inspectors have certified there is no danger of snow-laden roof collapsing."

The news coverage was equally as grim by papers in Washington, D.C.

"The catastrophe will rank among the most terrible on record," The Sunday Star newspaper declared the day after the tragedy underneath an all-caps, two-line headline blaring the death toll that was known about at that point. The Washington Star (The Sunday Star was the name of the paper's Sunday edition) went out of business in 1981, but the prediction in that news story holds true to this day.

Wurl said he thinks this information is important for people to know because there are always things that can be learned from the past.

|

"One thing that struck me in reading these stories was how far the science of meteorology has come -- the forecasts just before the 1922 storm were so inaccurate and incomplete," Wurl said. "But on the other hand, it seems there's still often a good deal of uncertainty today when it comes to predicting the impact of major storm events. In other words, in examining the past, you see both contrast and continuity, which I think is a common coincidence and lesson of human history in general," he added.

"Not knowing for sure, it's safe to say there were not the extensive, detailed type of warnings and watches we see today from the National Weather Service, but there were most likely some sort of advisories or notices sent in advance of and during the storm," Larson said.

Want next-level safety, ad-free? Unlock advanced, hyperlocal severe weather alerts when you subscribe to Premium+ on the AccuWeather app. AccuWeather Alerts™ are prompted by our expert meteorologists who monitor and analyze dangerous weather risks 24/7 to keep you and your family safer.