Explainer: What's behind ongoing protests in Georgia?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

For the past few weeks, thousands of protesters have gathered every night in front of the Georgian parliament in opposition to the controversial foreign agents law that the ruling Georgian Dream party is attempting to pass.

The final vote is set to take place on May 14.

The law would require organizations that receive foreign funding to be labeled as foreign agents. Opponents argue that it will stifle civil society and independent media and help the government suppress dissent.

The protests have begun to morph into a larger sign of discontent against the government and the direction it is taking the country.

Georgian Dream's Honorary Chairman Bidzina Ivanishvili, widely seen as the man who calls the shots, has been increasingly open that he holds the reigns over the government, not Prime Minister Irakli Kobakhidze.

The country is headed for a parliamentary election in October, which will likely prove to be a pivotal moment for Georgia as it faces what many have described as a stark choice between the European path and Russia.

Georgian Dream has been in power for 12 years and has long pledged, at least rhetorically, to take the country into the EU.

Local media and NGOs largely believe that the attempt to reintroduce the foreign agents law, which was abandoned last year after similar protests, combined with growing anti-Western vitriol from Ivanishvili and other officials, demonstrates that Georgian Dream is no longer interested in pretending to seek EU integration.

Instead, Georgian analysts and journalists told the Kyiv Independent that the ruling party has made its choice to seek closer ties with Russia.

Protesters on the street "fully understand that after this (law), there is no future for Georgia, because a future with Russia, for us, is no future," said Katie Shoshiashvili, a corruption researcher with Transparency International Georgia, in an interview with the Kyiv Independent.

Georgia's European path

Georgia was one of the first victims of Russian imperialism after the fall of the USSR, with the Russian military unofficially backing Abkhaz militants who sought to break away from Tbilisi.

An estimated 25,000-30,000 were killed and more than 250,000 displaced in the Abkhaz War in the early 1990s. The Georgian government lost control over Abkhazia, which is currently still occupied by Russian-backed proxies.

The 2003 Rose Revolution, spearheaded by future President Mikhail Saakashvili, resulted in the ousting of then President Eduard Shevardnadze, formerly the USSR's foreign minister, and marked a clear indication of Georgia's path westward.

Under Saakashvili and the United National Movement (UNM), Georgia attempted to deviate from Russia's sphere of influence. Saakashvili is still seen by many in the West as a champion of Georgia's aim to join the EU but has a controversial legacy at home, marred by various scandals and accounts of police brutality and mistreatment of prisoners.

Amid deteriorating relations with Russia, Saakashvili sought to reclaim Georgian territories controlled by Russian-backed proxies, which resulted in a full-scale war in 2008.

Following the war, Georgia de facto lost control of 20% of its territory to Russia, but it did not abandon its desire for greater European integration.

Saakashvili and the UNM were weakened by the defeat in the war, and the 2008 financial crisis which was exacerbated by other calamities and unfulfilled promises. The pro-EU ruling party lost the 2012 parliamentary elections to a newly formed party – Georgian Dream.

"Georgian Dream was elected as pro-Western, and it promised to continue the pro-EU path that the previous government (started)," said Mariam Nikuradze, the co-founder and executive director of OC-Media, in an interview with the Kyiv Independent.

Power behind the throne

Bidzina Ivanishvili is Georgia's richest man, having acquired billions in the "Wild West" era of privatization in Russia in the 1990s.

"When someone makes this amount of (money) in Russia, they are not let out of Russia just like this," said Eto Buziashvili, a research associate at the Atlantic Council's Digital Forensic Research Lab, in comments to the Kyiv Independent.

The degree of direct control to which Russia has over Ivanishvili is debated, but "in many ways, we have reason to believe that Moscow is still able to call the shots when it comes to Ivanishvili's access to his own assets," said Tinatin Japaridze, a risk analyst at the Eurasia Group, in an interview with the Kyiv Independent.

An investigation by the NGO Transparency International Georgia alleged that Ivanishvili owns at least one business in Russia, although he said he would cease his activity in the country after entering politics. He likely maintains other business activity in Russia through offshore companies or relatives, the investigation said.

Despite Ivanishvili's regular statements that he wanted to pursue Georgia's deeper integration with the EU, "there were many assessments from the very beginning that he was coming to Georgia with a very clear plan to drag Georgia toward the Russian orbit," Buziashvili said.

Ivanishvili only served as prime minister for one year before resigning in 2013 and handing the reigns to Irakli Garibashvili. The first years of Georgian Dream's rule saw tangible steps toward Europe, namely the liberalization of the visa regime for Georgian citizens in 2017.

Nonetheless, this may have been just a token measure to placate the Georgian people, the vast majority of whom favored joining the EU, said Buziashvili.

Another possible explanation is that Ivanishvili and Georgian Dream did, and still do, legitimately want to join the EU, but in the mold of Hungary as an illiberal democracy and spoiler in the bloc. While many have argued that Georgian Dream should be characterized as pro-Russian, others are more skeptical if that label accurately captures the party's guiding philosophy.

Its current policies align most clearly with Russia, but ultimately, the party seeks to serve itself and its own interests, namely its hold on power; the analysts and journalists who spoke to the Kyiv Independent largely concurred.

Democratic backsliding

The various statements by Ivanishvili and Garibashvili and pro-EU negotiations aside, warnings of democratic backsliding appeared not long into Georgian Dream's rule.

The government's crackdown on media, NGOs, and political opposition increased over time, said Nikuradze. UNM members, including Saakashvili, were aggressively pursued and jailed. Ivanishvili and other Georgian Dream members constantly dredge up complaints about UNM and blame it for the 2008 war and other problems faced by Georgia.

The desire to punish Saakashvili's associates has become a fixation for Georgian Dream and led to diplomatic disputes with Ukraine after Saakashvili sought to restart his political career there in 2015.

Saakashvili is currently languishing in jail after a failed bid to reenter Georgia in 2021, and his health is reportedly in decline, prompting criticism from President Volodymyr Zelensky.

Georgia has also repeatedly sought to extradite other former members of Saakashvili's team who are involved in Ukrainian politics, which Ukraine has refused.

As the relations between Georgia and Ukraine have continued to deteriorate, Georgia released an official statement in March expressing "deep concern regarding the attitude demonstrated by the Ukrainian authorities towards the friendly country of Georgia and its people."

One of the pivotal moments in which it became clear that Georgian Dream had drifted away from the European path was in 2019 when Russian lawmaker Sergei Gavrilov was invited to speak at the Georgian parliament.

The invitation, issued in part by current Prime Minister Irakli Kobakhidze, led to massive protests and a subsequent violent police crackdown, widely seen as disproportionate.

Georgian Dream 2.0

The Georgian Dream of May 2024, which is intent on ramming a highly unpopular law in the face of massive public protests and warnings from the West, is a different party than the one elected in 2012, several analysts and journalists told the Kyiv Independent.

A turning point was the beginning of Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine, which many Georgians took personally, as it reminded them of their own experience with Russian aggression.

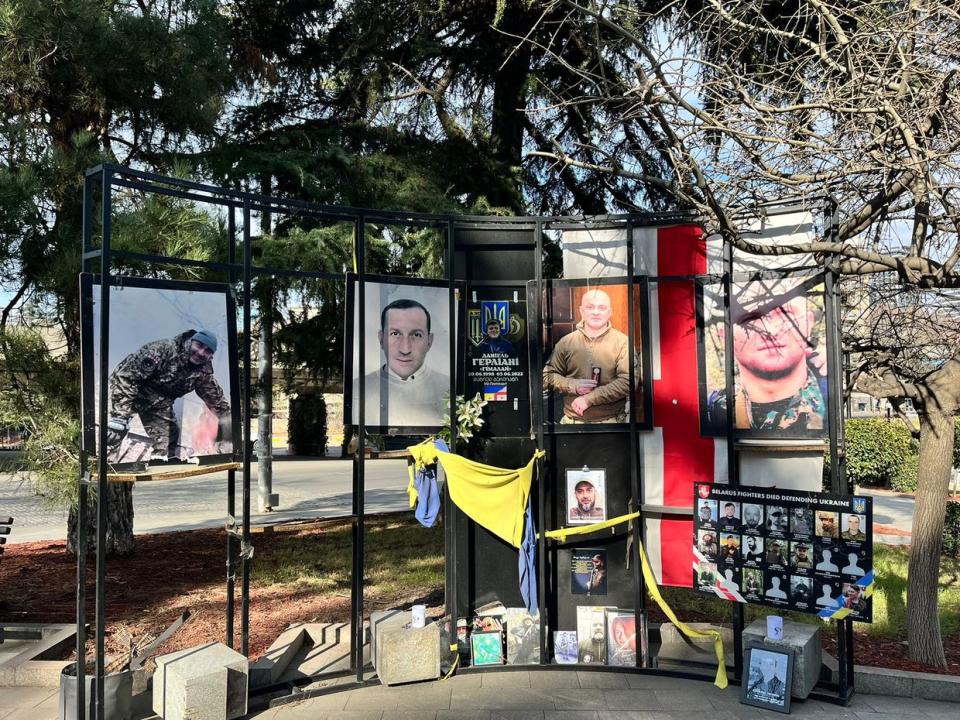

Georgians have broadly supported Ukraine and its fight against Russia, and significant numbers of Georgians have joined volunteer legions. Reports have indicated that more Georgians have been killed fighting for Ukraine than citizens of any other foreign country, a striking statistic given that Georgia's total population is around 3.6 million.

The government's decision to introduce the foreign agents law in March 2023 sparked large-scale demonstrations, and after a few days, Georgian Dream backed down in the face of overwhelming public anger.

Given that the government was largely seen as defeated by protesters on the street in 2023 and that Georgian Dream leaders pledged not to revive the bill, the decision to bring back the law in April confounded and angered many Georgians.

The reaction from the public has been swift and overwhelming, surpassing the scale of similar protests last year. "The (situation) feels very similar," Nikuradze told the Kyiv Independent, "but I think what is different is that people are way angrier."

"(Georgian Dream) completely miscalculated with this move," Japaridze told the Kyiv Independent. "They have lost touch with knowing what makes the general Georgian public tick."

Yet, despite the protesters' clear determination and the explicit warnings from EU officials that the law's passage will hurt Georgia's chances of joining the bloc, the government appears determined to ram it through.

Kobakhidze and other Georgian Dream leaders have taken to spouting bizarre statements that are plainly false, such as the notion that the foreign agents law is somehow required for Georgia's accession to the EU.

"We've unfortunately used the term 'Orwellian' (so much) that it has kind of lost it's meaning, but this is a truly 'Orwellian' (situation)," said Buziashvili.

Tbilisi Mayor Kakha Kaladze appropriated the protesters' refrains in a widely mocked Facebook post on May 7, saying, "Yes to the Georgian law, no to the Russian law, yes to Europe, yes to transparency."

Kaladze is a member of Georgian Dream and supports the foreign agents law.

As the protesters have remained undeterred, repeatedly showing up despite rain, the Easter holidays, and an increasingly brutal police response, Georgian Dream has shown a willingness to escalate both rhetorically and in its violent tactics.

Ivanishvili and Kobakhidze have accused the West of fomenting a potential revolution in Georgia and pledged to "punish" its perceived political opponents.

Local media have reported that protesters have been shot with rubber bullets, including in the eyes, and riot police have singled out individual peaceful demonstrators for beatings and arbitrary detentions.

In a callback to the tactics of former Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych, there have also been reports of the usage of so-called "titushki," or paid masked mercenaries, who have attacked protesters.

Lado Abkhazava, a teacher and advocate for EU integration, was assaulted by unknown assailants with bats outside of his home in Lanchkhuti, a city some 300 kilometers from Tbilisi.

Georgian opposition leaders have welcomed Western condemnation of the draft law and the crackdown on protesters but urged further measures, namely specific sanctions on Ivanishvili and other Georgian Dream officials.

Read also: Georgian government holds massive anti-West rally as it aims to pass ‘Russian-style’ law

We’ve been working hard to bring you independent, locally-sourced news from Ukraine. Consider supporting the Kyiv Independent.