Exclusive: Inside secret torture prison run by Ukraine's Russian-backed separatists

He says it felt like an earthquake.

For three days in a row, Ruslan Zakharov was taken to the basement of a prison that does not technically exist, where his captors would take a field telephone, attach electrodes to his limbs and send electric shocks through his body.

“It shakes you all up so hard: half of your body goes numb,” Mr Zakharov, 31, recalls. “You think they’re going to kill you: you feel helpless. You think you’re alone and no one will come to your rescue.”

Mr Zakharov, who used to live in a frontline town in eastern Ukraine, was tortured at Izolyatsia, a crumbling factory in the Russian-separatist-controlled city of Donetsk.

The building was a modern art hub before it was turned into a torture chamber after war broke out in 2014.

Victims of torture have revealed details about the separatists’ clandestine prison in rare interviews with The Telegraph, telling how men were placed on hanging racks and inmates were waterboarded and forced to fight each other.

These men and women are now suing both Russia and Ukraine at the European Court of Human Rights as their tormentors remain out of reach for Ukrainian law enforcement.

Mr Zakharov had been shuttling people and goods across the front line for five years when he was stopped at a checkpoint leaving the separatist-held area in October 2019, and told he was a Ukrainian spy.

He was hooded and handcuffed and taken to what appeared to be the office of a Soviet-era factory. But the wood-paneled rooms had metal doors attached to them.

This was Izolyatsia, or "Isolation" in Russian, Donetsk’s most feared prison. It does not legally exist even in the separatists’ self-styled system.

“Did you get it?” his captors would yell at him and smack him with a live wire at the prison’s basement with bare cement walls.

“They were beating the truth out of me for three days,” Mr Zakharov says. “They wouldn’t believe it, then they would shake me up with electricity so hard that I had to make up things so they would stop.”

When he was not lying on the desk, duct-taped and electrocuted, he was forced to stand in his cell with his face against the wall and arms stretched over his head.

The cab driver never produced a story to his captors’ liking, and was transferred to a detention centre ten days later where he began to recover from torture.

Mr Zakharov and his mother ended up paying more than $12,000, borrowed from family and friends, to a separatist security official before he was released at the end of October 2019.

The two fled to the Netherlands where they applied for political asylum but Mr Zakharov, tired of waiting, came back to Ukraine.

“Izolyatsia is a secret place which is off limits for relatives or even other separatists,” said Tetyana Katrychenko, of the Kyiv-based Media Initiative for Human Rights, who has interviewed 25 former prisoners.

Widespread abuse has been reported on both sides of the conflict but Izolyatsia's elaborate torture systems makes it stand out.

“A former prisoner told me when he got to Donetsk’s pre-trial detention centre, it felt like paradise to him after all the hell he went through at Izolyatsia,” Tanya Cooper, of the United Nations Human Rights Monitoring Mission in Ukraine, told The Telegraph.

At least 90 people have reached out to Ukrainian authorities about torture at Izolyatsia but there are hundreds of undocumented victims, according to Roman Tsyb at Ukraine’s Prosecutor General’s Office. Mr Tsyb is in charge of prosecuting crimes at illegal prisons in separatist-held areas and is pursuing charges against 50 people suspected of torturing inmates at the former factory.

Most of Izolyatsia’s prisoners are random people whose capture has helped the self-proclaimed authorities to stoke war sentiment.

Valentina Buchok was an electrician in Donetsk when she was snatched by a man near a dilapidated block of flats.

She was told she was suspected of doing reconnaissance for the Ukrainian army near the house where a prominent warlord was killed in an IED explosion four months earlier.

The same evening, she was brought to Izolyatsia with a bag over her head. “The door slams behind you, and you no longer exist,” Ms Buchok says.

“Men were screaming so hard, they would lose their voice. I could hear the sound of electricity cackling and the duct tape slapped on.”

In a heavy-edited video shown on local TV in March 2017, Ms Buchok says she was asked by Ukrainian intelligence to take a picture of the warlord’s house.

Ms Buchok, 55, says she had no choice but to sign a confession.

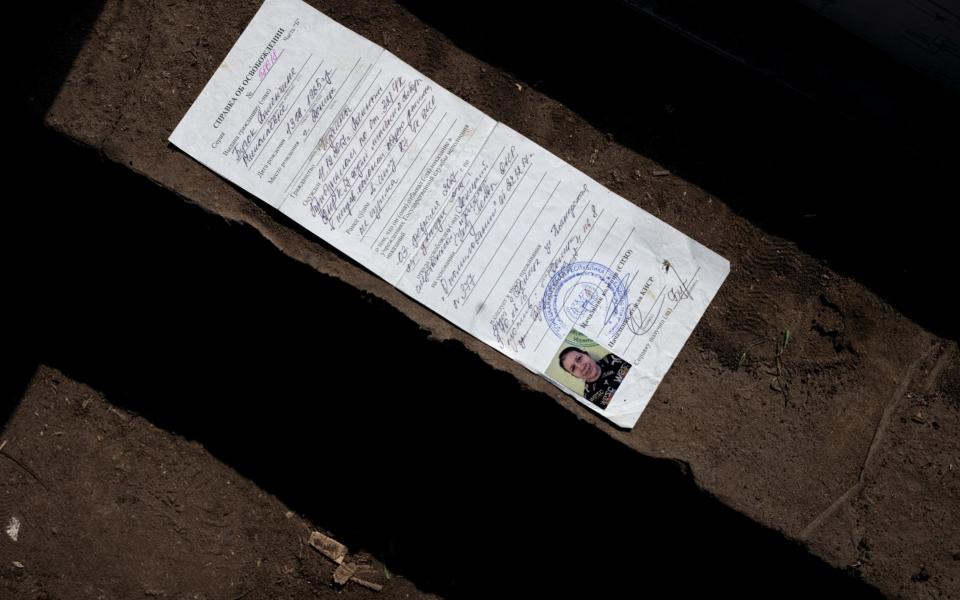

She was released in a prisoner swap at Christmas 2019. Her only memento from Isolyatsia is an elongated piece of paper with her mugshot: a prisoner release form. She now now lives in an unfinished house some 20 kilometres away from the front line.

Izolyatsia, under the leadership of the infamous former policeman known as “Palych,” was manned by former civilians who revelled in violence.

“They were particularly cruel, beating confessions out of people and demonstrating their power,” Ms Katrychenko said. The inmates The Telegraph spoke to said they saw CCTV cameras in their cells.

“Palych” would force prisoners to fight each other and watch it on the screen in his office, according to Ms Katrychenko.

Sexual violence at Izolyatsia is also common but most victims refuse to go on the record about it.

Last year’s report by the Office of the UN High Commissioner on Human Rights said nine out of nearly 40 detainees released in the December 2019 prisoner exchange and interviewed by the UN reported being subjected to sexual violence.

“Palych”, the master of torture, was reportedly fired in 2018 but Izolyatsia remains Donetsk’s most feared place.

When Maria, a woman from Donetsk who asked not to use her real name for fear of persecution, saw her husband three days after he was taken away by plainclothes officers, she knew Sergei had been tortured: his wrists were lacerated, smeared with iodine and filled with pus.

She later discovered her husband had been hung up on a rack, waterboarded, and subjected to electric shocks. Guards would also put out cigarettes on his back.

Sergei was tortured at Izolyatsia for a week before he was told that his wife would be brought in and tortured in front of him: he signed a confession, incriminating himself as a Ukrainian spy.

“An investigator told me: you have to understand he’s just prisoner swap material,” Maria told The Telegraph over the phone from Donetsk.

Sergei is now awaiting trial on spying charges in a regular prison. A number of victims who were released from Izolyatsia in prisoner swaps are wary about going to officials.

“Some people give up hope because they don’t see any result - and the only result here can be a court ruling,” Mr Tsyb, the Ukrainian prosecutor, told The Telegraph while on a field trip in eastern Ukraine.

Ukrainian authorities are hoping to change that: the first criminal case into torture at Izolyatsia was sent to court last month.

Nine former prisoners have testified against another former inmate, Evhen Brazhnikov, who is accused of being an accessory to torture and ill-treatment by the Izolyatsia administration for five years before he was released in 2019.

Several Izolyatsia victims, despairing of seeing justice done at home, have lodged lawsuits in the European Court of Human Rights against Ukraine and Russia (only recognised governments, not the self-proclaimed authorities in Donetsk, can be held accountable at the Strasbourg-based court).

But it will likely take years before former inmates get their hearing in Strasbourg: so far only a handful of the 50 lawsuits have been communicated to the respondent governments, which is the first stage of legal proceedings at the ECHR.

Mr Zakharov, who is trying to rebuild his life after a week of torture in Donetsk, is one of the claimants. He is hoping for at least an acknowledgement of what happened to him while his tormentors have faced no consequences.

“I don’t have much faith that Ukraine will get them - at least in the short term,” he said.

There is also some hope of action at the International Criminal Court in the Hague, which in December admitted that a “broad range of conduct constituting war crimes” has been committed in eastern Ukraine. That finding opens the door to a potential trial.

Separately, activists at the Media Initiative for Human Rights are working to identify Izolyatsia employees so they can be targeted with visa bans and asset freezes under the UK’s Magnitsky law.

Maria Tomak, coordinator at the Media Initiative, calls it a “signal on a personal level that if you were going to move to ‘Londongrad’ after torturing people at Izolyatsia and enjoy life there, it’s not going to work.”