Prosecutors Finally Grilled Sam Bankman-Fried. It Was Agonizing.

This is part of Slate’s daily coverage of the intricacies and intrigues of the Sam Bankman-Fried trial, from the consequential to the absurd. Sign up for the Slatest to get our latest updates on the trial and the state of the tech industry—and the rest of the day’s top stories—and support our work when you join Slate Plus.

On Monday, Sam Bankman-Fried finished taking questions from his own counsel and began his cross-examination by the prosecution. Weirdly, it reminded me of one of George W. Bush and John McCain’s presidential showdowns.

During the 2000 GOP primary, Bush and McCain spent much of their South Carolina debate squabbling with each other over some rather vicious insults Bush supporters had visited upon McCain. After the Arizona senator claimed to have “pulled down” his own press attacks against Bush, the Texas governor pulled out a sheet of paper featuring an “attack piece” on Dubya that “had ended up in a man’s windshield” just the day before. “That is not by my campaign,” McCain bristled. “Well, it says ‘Paid for by John McCain’!” Bush retorted, eliciting audible guffaws from the studio audience.

Imagine such a moment on a loop, but set in a courthouse and staged between an evidence-hoisting prosecutor and a brusque defendant, and you have a good idea of what it was like to watch Bankman-Fried’s testimony live on Monday afternoon. Bankman-Fried deflected. Assistant U.S. Attorney Danielle Sassoon produced receipts. Again and again.

The first notable evidentiary smackdown occurred when Sassoon questioned SBF about his fall-from-grace media tour beginning last fall, alluding to the statements he’d made to countless journalists in the months immediately following the FTX bankruptcy. “You also did an interview hosted by someone named Mario Nawfal,” Sassoon stated, referring to the Twitter crypto influencer. “Do you recall that?” “Not specifically,” said Bankman-Fried, “but I am not saying I didn’t.” Sassoon then walked through the timeline up until the Dec. 1 Twitter Space in question, which seemed to jog SBF’s memory a bit. “Isn’t it true—yes or no—that you stated on this podcast that you were not involved at all in Alameda trading and hadn’t been for years?” Sassoon then ventured, referring to Bankman-Fried’s now-defunct crypto hedge fund Alameda Research. “I don’t recall what I said,” the defendant said, and shrugged, spurring Sassoon to play the relevant audio for the court. From a man who sounded a lot like Bankman-Fried: “I wasn’t super involved in Alameda. I was not involved at all in the trading. I hadn’t been for years. I was intentionally not getting involved in it because I was concerned about the conflict of interest.” After shutting off the tape, Sassoon asked, “That’s your voice, Mr. Bankman-Fried, correct?”

“It sounds like it,” Bankman-Fried kinda-sorta affirmed. (It was definitely his voice; I had listened to that Twitter Space live back in December.)

Bankman didn’t get any less evasive from there as Sassoon inquired about the journalists he’d spoken to over that time period: the Financial Times’ Joshua Oliver, CNBC’s Kate Rooney, the Wall Street Journal’s Patricia Kowsmann, the New York Times’ Andrew Ross Sorkin, and Bloomberg’s Zeke Faux. “Back in early December 2022, didn’t you admit to several reporters that Alameda had been allowed to exceed normal borrowing limits on the FTX exchange since its early days? Yes or no?” Sassoon probed. When SBF said he didn’t “remember saying it in that way,” Sassoon then pulled up Oliver’s reporting from Dec. 3, reading out a line penned by the author: “ ‘He admitted that Alameda had been allowed to exceed normal borrowing limits on the FTX exchange since its early days.’ … Are you denying that you said that?” Bankman-Fried: “I don’t think I would have said that in that way. I am not sure exactly what that is referring to.”

Well, then, “is it your testimony that Josh Oliver wrote something you didn’t say?” The defendant: “I’m not sure.” But “you told other members of the media that Alameda’s account access on FTX was the same as other users, didn’t you?” SBF: “I’m not sure about the phrasing.” So Sassoon then pulled up part of an email the witness had sent on Feb. 8, 2022, to Kowsmann, making him read it out loud: “While Alameda is a user on FTX, their volume is a very small fraction of overall exchange volume, and their account’s access is the same as others.” (This statement was also quoted in the published Journal report.)

Sassoon didn’t use just examples from the media against the defendant; she also referenced his own tweets. “Do you recall—yes or no—telling your followers on Twitter in October that your support for regulation was contingent upon protecting customers?” Once again, a deflection: “I don’t recall that specifically, no.” A new government exhibit was submitted and displayed to the court: an @SBF_FTX tweet from that month. “On Oct. 19, 2022, you tweeted that your support for regulation was contingent upon protecting customers, right?” Bankman-Fried then couldn’t help but reply with a quick “yup.” Oh yeah, even when it came to documents from his FTX exchange: When SBF claimed he didn’t “remember” the “phrasing” with which he issued statements on FTX’s ability to prevent clawbacks from customer accounts, Sassoon pulled up a marketing deck for the company and made Bankman-Fried read the “two words” under a heading of how FTX was “solving issues” apparently rampant in the crypto industry. Those words? “The first word is preventing, the second word is clawbacks.”

14) But my support for any particular bill, framework, etc. is absolutely contingent on those points--contingent on them actually protecting customers, and them actually protecting economic freedom.

Anyway, here's the blog post link once again: https://t.co/O2nG1VrW1l.— SBF (@SBF_FTX) October 19, 2022

OK, sorry, just one more, and I’m not even gonna bother to preface this one:

Sassoon: After FTX declared bankruptcy, isn’t it true that one of the first things you did was try to restore your administrative access to [FTX’s Amazon Web Services] database?

SBF: That’s not how I would put it.

Sassoon: Isn’t it true that in the weeks following the bankruptcy, you asked to have your access to the AWS database restored?

SBF: I was not specifically looking for my personal access to the AWS database.

Sasson: Isn’t it true you were requesting AWS access?

SBF: I was requesting it on behalf of the joint provisional liquidators in the Bahamas.

Sassoon: So, yes or no: You made requests to restore access to the AWS database?

SBF: I’m not sure exactly what you’re referring to here.

Judge Lewis Kaplan: Look, could you just answer the question instead of trying to ask the questioner what she’s referring to?

SBF: OK. No.

Sassoon: Isn’t it true that you made to-do lists after FTX’s collapse that included things like “try to get AWS access”?

SBF: Probably.

Sassoon: And so isn’t it true that you were trying to get AWS access after FTX declared bankruptcy?

SBF: Yes.

Yeesh—all that just to get a “yes.” It wouldn’t be the only time the clearly frustrated judge would butt in. After Sassoon asked at one point if SBF recalled, in substance, “making statements that FTX was a safe platform,” and the defendant agreed he did say “things that were sort of like that, yes, I am not sure exactly what you are referring to”—Kaplan rode in. “Mr. Bankman-Fried, the issue is not what she is referring to. Please answer the question.” For another moment, when Bankman-Fried gave a stiff “mhmm” as an answer to a spot margin–related query, Kaplan told him, “We need a word,” extracting from SBF an apology and a “yes.” It was both Sassoon and Kaplan who repeatedly requested that Bankman-Fried give a straight answer to, well, pretty much any question or topic of substance, not just the simple fact-establishing ones (“You were CEO of FTX International, yes?”) that earned his clipped “yup.” When SBF offered to “take a wild guess” regarding the 2021 FTX-Alameda MobileCoin fiasco, Sassoon clarified, “I don’t want you to take a wild guess.” In an exchange about FTX’s liquidation engine, SBF said, “I can explain if you want.” Sassoon brushed it off and asked a different question, only to get a “same response” from her interviewee. “What’s the answer, Mr. Bankman-Fried?” (Hey, that’s what we’re all trying to figure out, now, isn’t it?) I suspect that Kaplan was most infuriated, however, by another back-and-forth in which Sassoon questioned the witness over his attempt to access his shares of Robinhood, the online trading platform, following FTX’s bankruptcy—specifically, through a form signed by SBF proffering “unanimous consent” of Alameda’s board of directors to a stock transfer from the hedge fund to … FTX.

Sassoon: Looking at the bottom, you were the only member of the board, correct?

SBF: It looks like it.

Sassoon: Well, were you in fact the only member of the board?

SBF: I’m not sure which board of directors this is referring to. …

Sassoon: Do you see at the top where it says “Alameda Research, Unanimous Consent of Board of Directors, Stock Transfer”?

SBF: Yup.

Sassoon: And this is transferring the Robinhood stock to yourself, right?

SBF: Transferring it from one company that I was a partial owner of to another company I was a partial owner of. Sorry. I’m not sure it says it’s transferred to me.

Sassoon: This says, “Unanimous Consent of Board of Directors.” Looking at the bottom, you were the only member of the board, correct?

SBF: It looks like it.

Sassoon: Well, were you in fact the only member of the board?

SBF: I’m not sure which board of directors this is referring to.

…

Sassoon: So, the entity here, Alameda Research Ltd., you were the sole member of the board of directors, correct?

SBF: This makes it seem like I was, as of then. I probably was, as of then. It wasn’t my intention to be.

Sassoon: You said it wasn’t your intention to be. You signed this document, right?

SBF: Yes.

Sassoon: And this document says you were the chairman and sole member of the board of Alameda Research Ltd., correct?

SBF: Yup.

Kaplan: So, did you become director by mistake or accident or something else?

SBF: I’m not saying I didn’t approve this transfer. I absolutely did approve this transfer.

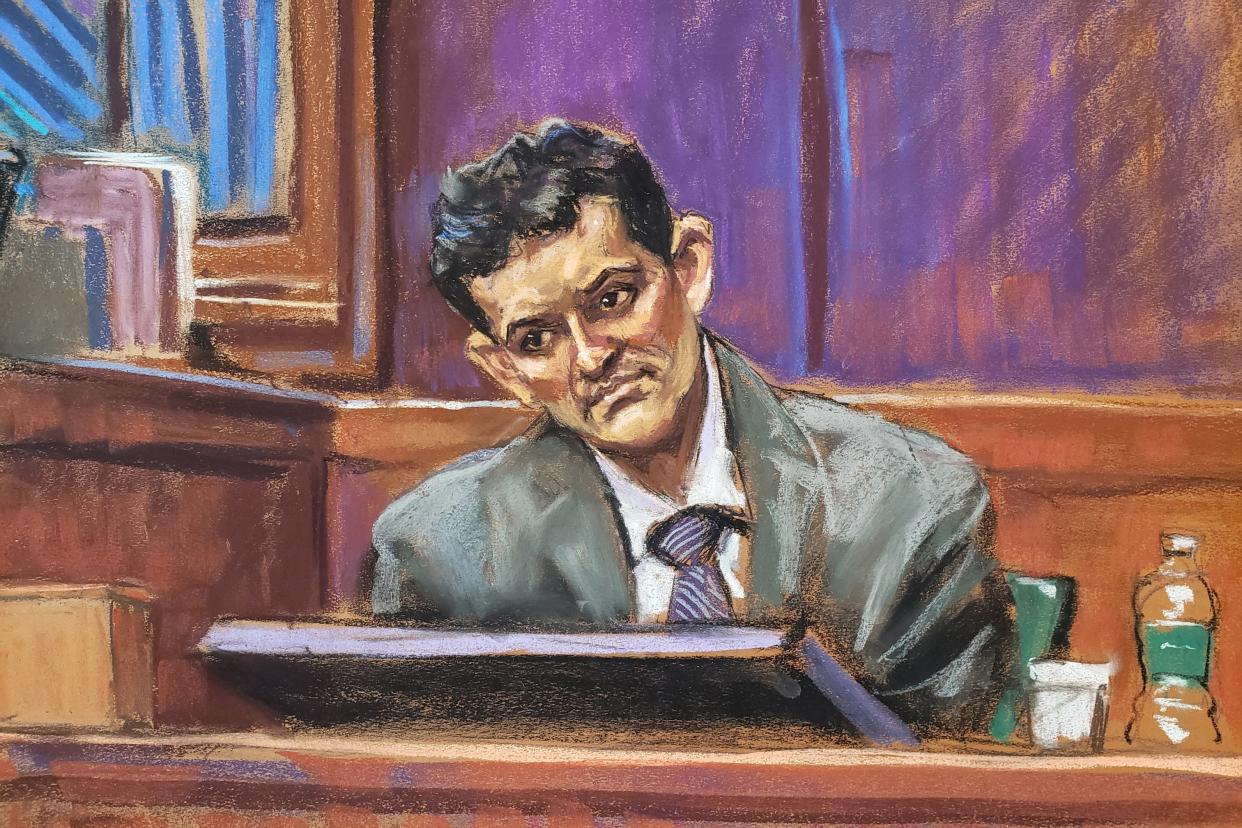

So, you must be wondering, what did we learn here? Well, it’s clear that SBF is taking somewhat seriously Kaplan’s repeated reminders that he’s under oath, although he’s sure attempting to filibuster his way out of committing to anything he’s asked. You could definitely see it in the witness box: Bankman-Fried was fidgeting throughout, shifting left and right in his seat, and glaring at the courtroom with a low-eyebrow glower and a consistent frown. There weren’t even too many halfhearted joke attempts like in his first days of testimony. The man was not enjoying it, he clearly wasn’t having it, and he was letting it be known. It reminded me a bit of his former colleague Nishad Singh’s testimony about how SBF would physically manifest his displeasure: “grinding his finger, closing his eyes, grinding his teeth or tongue in his mouth, and when he opened them to respond, he would sort of glare at me with some intensity.” I can definitely attest to seeing some finger-picking at his face and mouth, as well as some jammed-shut eyelids and slow, halting, unhappy answers to the prosecutor. His “yups” and offers to expound upon various things came off as rather insolent. Suffice it to say, I can’t imagine that it all endeared him to the jury that much. He might have been better off insisting, like John McCain in 2000, that this wasn’t his campaign.