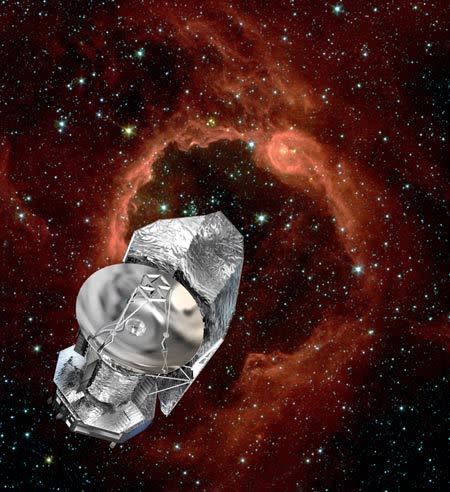

Europe Says Farewell to Prolific Herschel Space Telescope

PARIS — Ground controllers put Europe's Herschel Space Observatory to sleep Monday (June 17), turning off the infrared observatory after squeezing every bit of engineering value from the spacecraft since it ceased scientific work in April.

Engineers sent the final commands to Herschel at 8:25 a.m. EDT (1225 GMT) in an emotional ceremony at the European Space Operations Center in Darmstadt, Germany.

"It's like saying goodbye to a friend," said Micha Schmidt, the European Space Agency (ESA)'s operations manager for Herschel.

For its last act, the $1.4 billion Herschel telescope fired rocket thrusters to drain its fuel tank as controllers watched the spacecraft helplessly struggle to regain control while its antennas and power-generating solar panels drifted away from their lock on the Earth and the sun.[Photos: Herschel Observatory's Amazing Images of Deep Space]

"It's a very curious situation in that we are intentionally seeing a spacecraft dying," Schmidt said.

Herschel exhausted its supply of cryogenic helium, required to chill its science instrumentation to a temperature near absolute zero, in April after nearly four years of continuous observations of the cosmos. The telescope's frigid operating temperature allowed its sensors to detect heat from some of the coldest parts of the universe veiled from the view of optical cameras by dust.

Herschel's primary mirror spans 11.5 feet (3.5 meters) in diameter — 50 percent larger than the mirror on the Hubble Space Telescope. The instrument, named after 18th century German astronomer William Herschel, who discovered the infrared spectrum of light, transformed the field of infrared astronomy, according to Göran Pilbratt, Herschel's project scientist.

Launched in May 2009, the mission's credits include the discovery of vast reservoirs of water vapor in disks of gas and dust around infant stars. The water locked in such planet-forming disks could seed oceans like those found on Earth, according to scientists.

Herschel's infrared instruments also took images of networks of dust and gas filaments within the Milky Way, yielding a view of one of the earliest stages of star formation. The thread-like filaments could eventually coalesce into compact cores leading to the birth of new stars, scientists say.

But with Herschel's helium tank empty, the telescope's utility to scientists ended.

"The mission was planned for a duration of three-and-a-half years," Schmidt said. "We have been operating for four years, and the mission is a success."

Engineers programmed a rocket burn May 13 to guide Herschel away from its operating post at the L2 point, a gravitationally stable location about 930,000 miles (1.5 million kilometers) from Earth. The maneuver put the spacecraft into orbit around the sun on a trajectory that will not return to the vicinity of Earth for thousands of years, Pilbratt said.

During the last six weeks, controllers in Darmstadt put Herschel through a series of tests to push the craft's satellite platform and instruments to the limits.

"These are things you would never want to do on a live spacecraft because if you screw it up, you're going to make a lot of enemies," said Fabio Favata, head of ESA's science planning and community coordination office. "But for a spacecraft which has outlived its prime mission, it's something you can do."

ESA called for ideas across Europe on how to use Herschel as a testbed, and received proposals from satellite control teams, astronomers and designers of the ExoMars mission to the Red Planet and Euclid, ESA's next flagship-class space telescope.

Controllers switched Herschel to its backup systems to verify they were still functional after four years in space. Teams in charge of Herschel's three science payloads analyzed diagnostic data to gauge the health of the instrumentation, Schmidt said.

The last test involved turning Herschel away from its normal pointing mode and checking the ability of the spacecraft's onboard computer to autonomously detect and correct the error.

"This was quite interesting and a lot of fun," Schmidt said. "This was, more or less, the last test. It was the most dangerous test which we put toward the end of the test campaign."

Programmers sent commands to Herschel last week for Monday's fuel-draining engine burn, which was expected to put the spacecraft in a tumble leading to the loss of electricity aboard the observatory, which requires its solar panels to point toward the sun to generate power.

Controllers' last act was to transmit a command to Herschel to turn off its transponder and never turn its radio on again, according to Schmidt.

"I have the feeling that the spacecraft and the teams controlling the spacecraft are finished," Schmidt said. "We are turning off the lights now. We have delivered our package to astronomers around the world, who have all the data and can do what they want with it."

Pilbratt said the Herschel mission is funded by ESA through 2017 to process the telescope's vast data archive and preserve it for future scientists.

According to ESA, Herschel made 35,000 science observations and collected more than 25,000 hours of science data from 2009 until 2013.

"This is not the end of the mission," Pilbratt said. "It is the end of spacecraft operations."

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on SPACE.com.

Copyright 2013 SPACE.com, a TechMediaNetwork company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.