The Ethnic Odd Girl Out

“What are you?”

Those three short words have followed me around since childhood. I’ve been asked this question more times than I can count - on vacation, at the movies, in the frozen foods aisle, by nail technicians, bank tellers, and even customers at the clothing store where I worked in college.

And while the words may look harmless on paper, the question they form has carried a surprising amount of weight over the years. What are you? doesn’t refer to my occupation, religion, or physical composition (skin and bones, like everyone else). Instead, people are wondering about my ethnicity. They want to know exactly what I am.

What most of these people have in common has nothing to do with age, gender, or skin color. It’s that the majority of them are complete strangers to me - often times, we haven’t even discussed the weather before addressing the unidentified elephant in the room. The sudden question fazed me a lot more when I was younger, but I learned to expect it over time.

To be honest, I don’t have a problem with strangers being interested in my ethnicity. It’s why they’re interested that bothers me. It would be different if people were curious about my cultural roots, ancestors’ stories, or family traditions. But most of the time, the questions result from confusion about my physical appearance. What are you? essentially translates to: What racial mixture are you a product of? This surface level query concerns the color of my skin and the shape of my eyes - it has little to do with anything deeper than how I look.

And while most people are innocent in their curiosity, the question is the result of a culturally-driven need for labels. I usually just tell people that I’m half Chinese and half white, an answer that usually seems satisfactory. Some people probe further, in which case I explain that the white part of me encompasses Yugoslavian, British, Irish, and French. Oohs and ahhs ensue - mixed women are so exotic, right?

"I always felt out of place—too much of this or that, but never quite right."

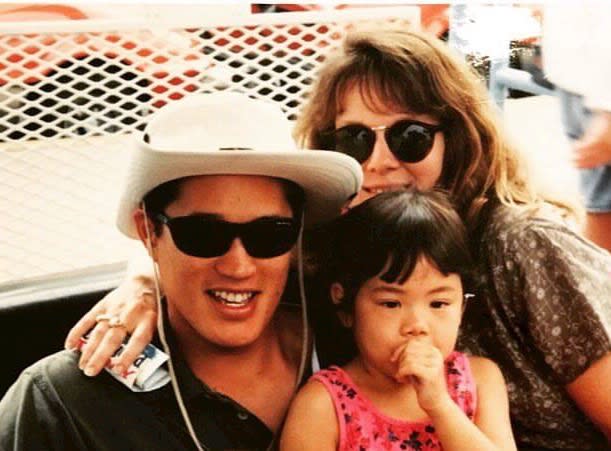

When I’m by myself, the conversation usually ends there. It’s only when I’m with one of my parents that the questions intensify. My Caucasian mother is fair with golden hair, while my Asian father was tanned with dark features. I inherited a combination of their traits - almond-shaped eyes, subtle dimples, and fair skin that never burns. I’ve always received very different responses depending on which parent I’m with.

One of my earliest memories of this was playing in a neighborhood park with my mom. She was pushing me on a swing when a woman approached us. “She’s so cute - is she adopted?” I didn’t really understand what adoption actually was, but I remember seeing the surprised look on my mom’s face. It wasn’t until I was older that we discussed what happened that time in the park. To this day, my mom and I often get asked about how we’re related or if I’m adopted. Sometimes we laugh it off, and other times it’s just plain frustrating.

My parents have always been candid about and their interracial marriage and how it wasn’t always accepted. They made sure that my sister and I understood our heritages and ancestry throughout childhood. We travelled abroad starting at a young age, something that I attribute to my eventual acceptance and embrace of my Hapa identity. Hapa is a Hawaiian pidgin word used to describe mixed-race people (usually those who are half Asian and half white).

Despite the values my parents instilled in me, there were still hurdles I had to overcome. We all noticed over the years that in public, it seemed like I was too Asian to be my mother’s daughter and too white to be my father’s. Thus began a confusing period of time when I always felt out of place - too much of this or that, but never quite right. That is the Hapa experience in a nutshell: struggling to find a balance between too Asian and too white.

I grew up in a pretty diverse city, but moved to a predominately Caucasian area at the end of elementary school. Before the move, I felt pressured to embrace more of my Asian side. I traded my PB&J’s for meat dumplings and even tried to learn Mandarin, but still, it wasn't enough.

After my family moved, I stood out once again - but this time, for a different reason. In addition to being the new girl, I was one of the few Asian students in my class. This continued throughout middle school and into early high school. Suddenly, my old school lunches and English vocabulary were tools to help me fit in. I ditched my Mandarin phrasebook and attempted (and failed) to contour my Asian nose.

Sometimes my friends would ask if I identified more with my mom’s side or my dad’s side. I didn’t know how to respond - the simple truth was that I didn’t know. I still didn’t understand exactly where I fit along the mystifying spectrum of ethnicity.

It continued to feel like I had something to prove to the world. I eventually realized that learning multiple languages and eating certain foods wouldn’t change the way people looked at me. There was a fundamental shift that needed to occur within my core.

It’s impossible to identify a specific event that changed my perspective. There was no aha moment or turning point that helped me embrace being Hapa. It was a long process with challenges and road bumps, doubts and uncertainty.

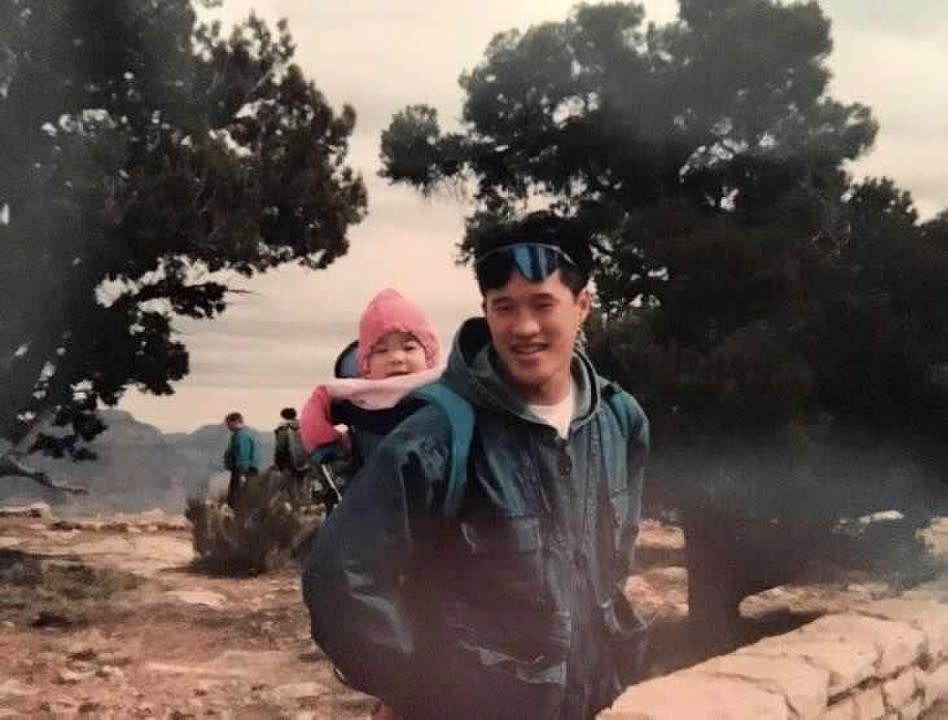

Looking back, though, I view traveling and my parents’ support as key elements along the way. Being removed from our neighborhood bubble helped me see the big picture - that there’s a huge, magnificent world out there, filled with all sorts of people and outlooks. I didn’t need to choose a side or feel more Asian or more white. I needed to embrace all the unique parts of myself, from my pale skin tone to my almond amber eyes.

When I think more about this mental shift, a conversation with my father comes to mind. I was having a particularly hard time adjusting to my second school, and he noticed the struggle. I explained that I’d recently had an awkward exchange with my new friends - they were poking fun at the Chinese New Year traditions I told them about. One girl wondered why I even celebrated it at all, since my family also partook in other New Year traditions. He listened to my story before imparting advice that I still remember today.

"I eventually realized that learning multiple languages and eating certain foods wouldn’t change the way people looked at me."

“You’re not half a person,” he told me. “You’re a whole person. Never forget that.”

Nowadays, being Hapa is something I’m very proud of. There are still tough moments when I feel like that confused girl again, but thankfully they’re few and far between. The thing is, people are always going to ask questions. There will always be strangers (and even friends) who wonder why you are the way you are. The questioning is rarely malicious, regardless of how it comes across. To echo age-old wisdom, the most important thing is how you feel about yourself.

When I look around, I see so much progress in terms of people embracing their individuality. Companies are running campaigns devoted to different types of beauty. There’s a plethora of fashion blogs dedicated to distinct groups of people (even Hapas). Hopefully one day, kids won’t grow up being asked solely about their ethnicities. If they are, I hope that there’s more of a conversation and interest in culture and background, motivated by something deeper than confusion over physical appearance.

Now, when someone asks, “What are you?” my sassy alter ego speaks up before I even have the chance. I am an author with my debut novel arriving this fall. I am a bright, creative, independent person. I am inspired by the strong women around me.

Danielle M. Wong is the author of SWEARING OFF STARS, an LGBT romance set against the 1920s gender equality movement.

You Might Also Like