Can de-escalation training help prevent police shootings? Here's what the experts say

Akron police officer Ryan Westlake stops his cruiser next to a teenager carrying what looked like a pistol on a tree-lined stretch of Brittain Road.

Westlake – once fired and then re-hired by the city after violent incidents both on and off the job – initially sounds calm, even friendly with the teen during the April 1 encounter.

“Where you comin’ from?” he asks 15-year-old Tavion Koonce-Williams through the open window of his cruiser.

Before Tavion can answer, Westlake opens his cruiser door and asks: “Can I see your hands real quick?”

Then, without warning, Westlake fires a shot that hits Tavion in the wrist.

Westlake seems almost as surprised as Tavion, exclaiming, “Oh, shit” as Tavion yells repeatedly that the gun he is carrying is “fake,” a toy that looks strikingly similar to a real pistol.

Tavion, bleeding, face down in someone's yard, pleads with officers in the moments after, saying he "just wanted to be safe."

The Ohio Bureau of Criminal Investigation is still gathering information about the shooting, and law enforcement academics interviewed for this story declined to weigh in on whether it was justified. Bodycam video alone, they said, doesn’t provide enough information to judge.

But Tavion’s family and some in the community are outraged by another police shooting of an African American, particularly a teenager carrying a toy gun.

Akron NAACP President Judi Hill has renewed her call for increased de-escalation training for Akron police.

But would that have prevented this shooting, and could it prevent others?

Police de-escalation training: Can it work?

Cincinnati was reeling in 2015 after a University of Cincinnati (UC) police officer shot and killed an unarmed Black man after pulling him over for driving without a front license plate near campus.

The incident drew worldwide attention, and UC at the time responded to the crisis, in part, by taking a very unusual step: Putting a professor, a criminal justice researcher, in charge of university police oversight and reform.

Robin S. Engel had never been an officer. But by then, she had spent two decades shadowing on-duty police across the country, using hands-on experience as part of her research into everything from best-practice policing to crime-reduction strategies.

At the time, the buzz about police de-escalation training was just beginning.

Engel was curious, but said during a recent interview she discovered there was no uniformity to de-escalation curriculum, nor research about what was effective.

Part of that lack of information was because many police officers pushed back against the idea of de-escalation, she said.

“They said, 'You’re going to teach us to hesitate…you’re going to get us killed,'” she said.

Police historically were taught to quickly resolve any situation with whatever force they needed before it could escalate.

De-escalation, long used by SWAT teams during standoffs and other assignments, instead teaches officers to take their time, keep their distance and take safe cover until a situation can be resolved.

Now, nine years later, there’s a growing body of research – in large part driven by Engel – that quality de-escalation training keeps not only citizens safer, but police officers, too.

Engel led perhaps the most comprehensive study, focusing on Louisville, Kentucky, police and what happened after the department implemented de-escalation training in 2019.

Louisville police relied on training developed by the nonprofit Police Executive Research Forum (PERF). PERF is part of a collaborative effort with the National Policing Institute and Bureau of Justice Assistance (part of the U.S. Justice Department) to create a curriculum and standards for police de-escalation training.

They call the training ICAT, and it’s anchored in critical decision making that helps frontline officers assess situations, make safe and effective decisions and document and learn from their actions.

The training focuses on policing people in a crisis and those who are armed with weapons other than firearms.

The randomized study of how well ICAT training worked in Louisville was released in 2022, and Engel said the results exceeded expectations − even hers.

It showed that after the training, the department had 28% fewer use-of-force incidents, 26% fewer injuries to community members and 36% fewer injuries to police officers.

One of the reasons it had such an impact, she said, is that Louisville had especially good trainers who officers trusted.

Engel said her research shows female officers are more likely to be receptive to de-escalation training. But, she said, police leadership can convince skeptical officers, too, by explaining how de-escalation training is there to keep both officers and citizens safe.

For the training to work long-term, she said, police supervisors must continually re-emphasize de-escalation.

In Ohio, only the University of Cincinnati and Dayton police departments use ICAT training, according to PERF’s website.

But Engel believes police across the country will soon adopt ICAT and similar training as best practice, marking an evolution in policing.

Do Akron police get de-escalation training?

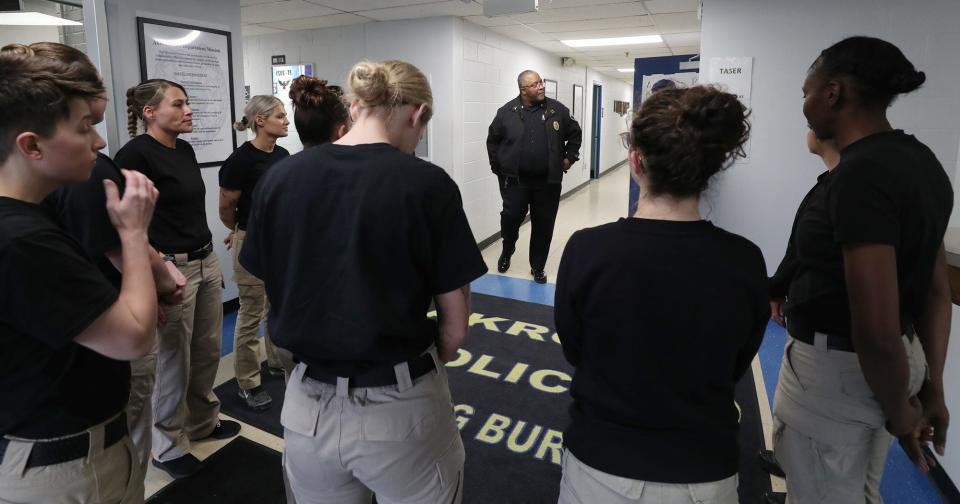

Police in Akron have long had de-escalation training, but the concepts and words used to describe it have changed over the years, Akron Police Capt. Michael Miller said.

Aspiring officers start out with 24 hours of crisis intervention training from the Ohio Peace Officer Training Academy, or OPOTA.

De-escalation is also built into other training, including how to control a person, ethics and professionalism and critical incident stress awareness, he said

Then, after the academy but before Akron officers hit the street, the department provides another eight-hour course in de-escalation, he said.

But de-escalation training doesn’t end there. Yearly training continues.

In the past, it was called “street survival” or “verbal judo,” Miller said.

But whatever the training was called, it was about “the ability to communicate effectively and from a position of safety [that] allows for our officers to have discretionary time to make decisions.”

Akron officers certified to carry a Taser also have yearly training, which includes at least one de-escalation scenario using virtual reality.

The virtual situation changes in real time, with threats and tension rising and falling depending how an officer is responding.

“On top of that, the entire department reads and tests on our [use-of-force] policy annually, which says, ‘When dealing with an angry, agitated, or non-compliant subject, the objective is to utilize de-escalation techniques to calm the individual and obtain voluntary cooperation’ in the opening paragraph,” Miller said.

The department has also provided other de-escalation training in recent years for all sworn officers.

Brian Lucey, president of the Akron FOP Lodge 7, said police believe in de-escalation and pointed out that Akron police have received awards for their overall training.

Most recently, in November 2021, the Akron police training academy was the first in the state to earn STAR certification from Ohio Attorney General Dave Yost.

In Ohio, all police are required to have 737 hours of training.

Academies like Akron’s, certified by Yost’s STAR program, must meet at least a dozen extra criteria, including that 85% of cadets eligible to take the state certification exam pass.

“The more training we have, the better the outcomes,” Lucey said.

But he worries that some see de-escalation training as some sort of “magic fairy dust” that will eliminate all police use of force.

It can’t, he and others who study de-escalation say.

Many hoped police shootings would drop after promises of police reform, particularly over the past decade.

But The Washington Post reported that U.S. police shot and killed more people in 2023 than ever before – 1,162.

‘Guns are everywhere in the U.S.’

Guns are everywhere in the U.S., said Katherine Schweit, a lawyer, professor and former FBI special agent executive who created the FBI's active shooter response program.

In 2020, the National Shooting Sports Foundation – the gun industry’s trade group – estimated there were 433.9 million firearms in the hands of about 331 million U.S. residents.

During the pandemic, Schweit said, 60 million more guns were sold with about 5% purchased by new gun owners.

“That’s about 12 million people with no experience with guns,” she said.

In a country where laws allow more people to carry guns, law enforcement must calculate new risks, she said.

Schweit watched the police body camera video of Westlake shooting Tavion and shared several takeaways, even though she said she didn’t know enough to say whether the shooting was justified.

In this case, a woman walking her dog called the non-emergency Akron police number after seeing a teen “aiming a gun” at houses in Goodyear Heights.

Schweit said it wouldn’t matter if that information came to the non-emergency police line, 911 or from someone who flagged down an officer on the street, police would react the same.

With so many people carrying so many guns, police often determine a threat by whether the gun someone is carrying is holstered or unholstered.

“Action is faster than reaction. If you raise a gun to shoot me, I’m not going to be able to react as quick,” she said. “That’s basic gun 101, and therefore, a law enforcement officer responding [to a call involving a gun] has to be prepared they may be fired on before they get out of their car.”

The gun Tavion was carrying turned out to be a toy, but Westlake didn’t know that. Because it was a toy, Schweit said she doubts Tavion had it holstered, emphasizing that Tavion did nothing wrong.

The initial words from Westlake to Tavion are more conversational than confrontational, reflecting what many police are now taught, she said.

“He didn’t roll down the window and yell, 'Drop the gun!'” she said. “What you heard out of that officer’s mouth is de-escalation.”

Why Westlake pulled the trigger is not clear.

“Law enforcement eyes go right to where the barrel of a gun is,” Schweit said.

Bodycam video doesn’t show what Westlake saw, nor other circumstances that may have influenced him pulling the trigger, she said.

“It may have been an accidental trigger pull. We just don’t know,” she said.

Schweit praised Tavion for telling officers the gun was “fake,” and she also praised the officers who arrived moments after the shooting and put a tourniquet on Tavion’s arm to slow the bleeding.

“Within seconds, they were tending to that young man,” Schweit said. “Years ago, law enforcement wouldn’t have the equipment to do that or know how. I love to see that.”

That’s the benefit of good training, she said, and something police everywhere need more of, suggesting that police should train as often as firefighters, which often doesn’t happen in small departments.

In the end, she said Akronites should watch the bodycam video and do their own analysis.

“It’s an opportunity to see how challenging it can be for law enforcement to have to make a decision and how quickly,” she said.

Schweit again said she was not justifying the shooting, but asked the community to consider: “What should the law enforcement officer have done differently given the information he had at the time?”

Echoes of Tamir Rice shooting

At a press conference 12 days after their son was shot by police, Tavion’s parents still looked rattled – not only by what happened, but also about what could have happened.

Tavion’s mom Angela Williams said she was thinking about Tamir Rice, the 12-year-old Cleveland boy shot and killed by police in that city a decade ago.

“Ten years later after Tamir Rice, I’m here speaking about my son,” Williams said. “I watched his mother speak about her son, and I’m standing up here doing the same thing.”

There are parallels between the cases: Both boys were Black. Tamir was 12; Tavion is 15. And both were carrying fake guns and both were shot by white officers with deeply troubling police records.

Timothy Loehmann, the officer who killed Tamir, had previously worked as a cop in Independence, where a supervisor said he was emotionally unstable and unable to properly handle a firearm.

He quit before being fired, something he did not disclose when Cleveland police hired him. Loehmann then quit his Cleveland job after killing Tamir and took a police job in Pennsylvania until locals there found out he was the officer who killed Tamir. Loehmann resigned from that job in 2022.

In Akron, former city police auditor Phil Young raised concerns about the large number of use-of-force incidents involving Westlake in November 2021.

“This guy should have been removed — in my opinion — a long, long time ago,” Young told the Beacon Journal recently. “They are giving too many chances.”

Among other things, Westlake has been involved in more than 30 use-of-force incidents during his nine years in the police department. Police supervisors found all but one of these uses of force, which included Taser deployments, punches, and takedowns, to be reasonable.

He was suspended or reprimanded five times.

And in 2021, then-Mayor Daniel Horrigan fired Westlake after two drunken domestic violence incidents. During one in Cuyahoga Falls, his girlfriend said Westlake pointed a gun at her and threatened to kill her and her father. Westlake, however, was soon re-hired by Akron police and given a 71-day suspension.

It’s unclear if better or more training would have prevented either Loehmann or Westlake from shooting the boys.

Imokhai Okolo, the Akron attorney representing Tavion and his family, did not return messages left by a Beacon Journal reporter for this story.

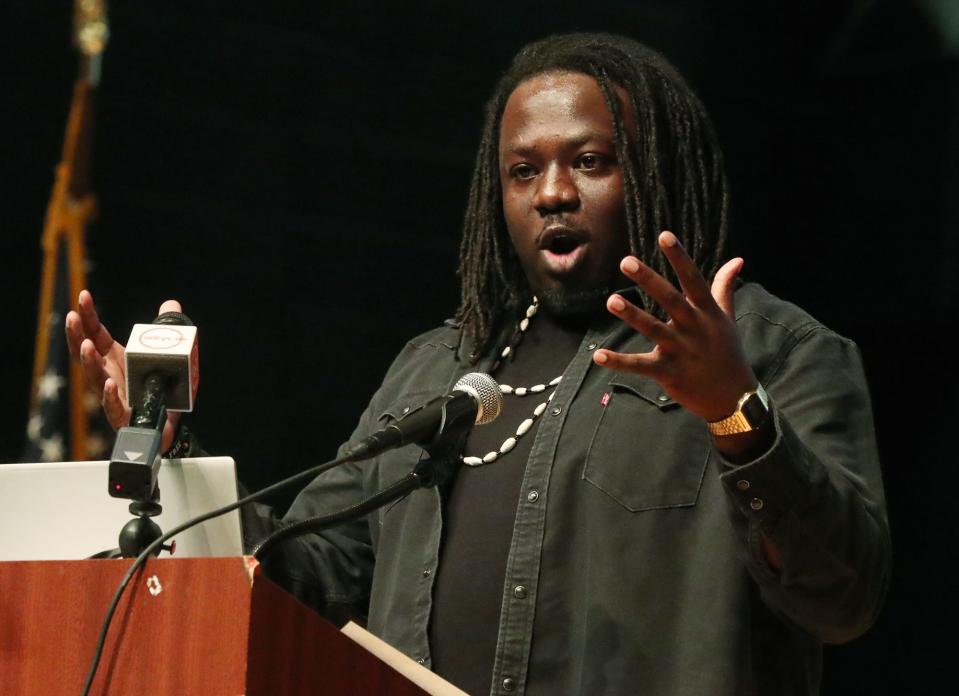

At the press conference, however, he made several demands, including that the city of Akron immediately fire Westlake and investigate officers with a similar pattern of departmental violations.

He also called for the U.S. Justice Department to launch a pattern and practice civil rights investigation into Akron police, which could force Akron to change how it polices.

For Black lives, Okolo said, “we know that power concedes nothing without a demand.”

This article originally appeared on Akron Beacon Journal: Experts weigh in on de-escalation training after Akron police shooting