Environment watchdog criticizes Canada's handling of risky, costly contaminated sites in the North

Canada's environmental watchdog is criticizing the federal government's handling of contaminated sites in the North, saying large abandoned mines present immediate and long-term risks to the environment and people's health.

In an independent auditor's report tabled in Ottawa on Tuesday, Jerry DeMarco, the federal commissioner of environment and sustainable development, said Canada's contaminated sites also carry financial risks which are becoming more expensive.

Canada has more than 24,000 contaminated sites in total, and the audit found that the federal government's liability for them has grown from $2.9 billion in 2005, to $10.1 billion in 2023.

"This is an enormous financial burden on taxpayers and represents a failure to properly implement the polluter pays principle, as many private sites had to be taken over by the federal government," DeMarco said during a media conference.

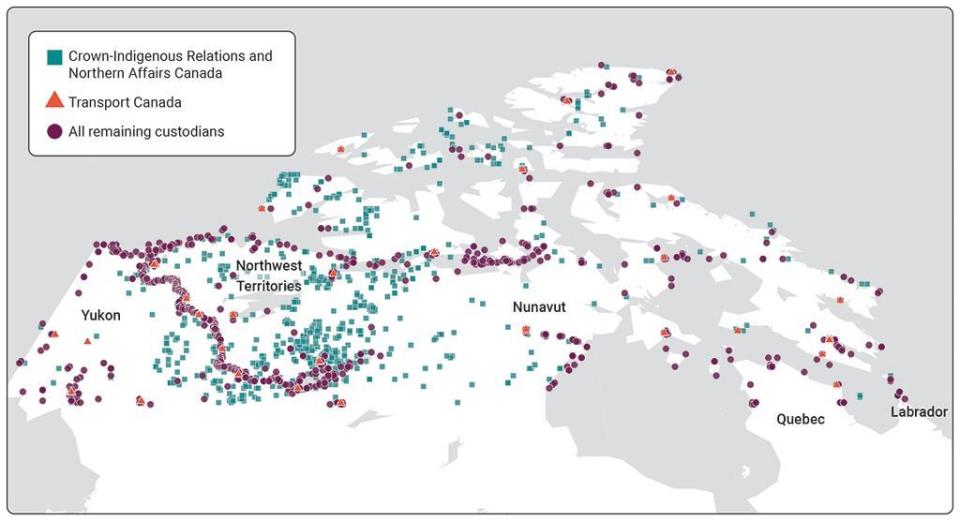

The North is home to more than 2,600 contaminated sites and represents 11 per cent of them across the country — but DeMarco said it's where 60 per cent of Canada's financial liability for contaminated sites lies.

He said the cost of remediating the North's eight biggest sites, a list that includes Giant Mine in the N.W.T. and Faro Mine in the Yukon, had ballooned 95 per cent since 2019 in part because estimates about the level of work that's needed to clean them up have become more accurate.

DeMarco found that although departments complied with the Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan, which has managed contaminated sites across the country since 2005, that compliance was "not enough" to meet Canada's objectives of reducing costs and risks. It also found the plan did not have realistic goals for adapting to climate change and involving Indigenous peoples.

A map in the report which includes all of the contaminated sites in the North, including those that are active, closed, or suspected. (Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development)

Giant and Faro examples of high-risk mines

The audit, which took place between March 2019 and October 2023, examined the Giant and Faro mines to get a better sense of how Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada (CIRNAC) handles large, high-risk abandoned mines in the North.

Giant Mine is an abandoned gold mine, and remediating it is an extraordinarily complicated undertaking that includes freezing 237,000 tonnes of highly-toxic arsenic trioxide underground and preventing groundwater from carrying it into bodies of water.

Faro Mine, meanwhile, was once the world's largest open-pit lead-zinc mines, and now consists of 70 million tonnes of tailings and 320 million tonnes of waste rock.

In both cases, the audit found remediation costs had "increased significantly" while contamination remained on site. Back in 2022, officials with the Giant Mine remediation said the project had grown from $1 billion to $4.38 billion.

The audit also found that while remediation work at Faro had "exceeded" targets for training women, northern and Indigenous people, similar targets for Giant's remediation had not been met. Northern Indigenous workers were supposed to have worked 25 to 35 per cent of work hours at Giant one year, but had only worked 18 per cent.

"Several Indigenous communities told us that the federal government had missed opportunities to advance on its reconciliation commitments to leverage these large remediation projects," the report said.

The report recommends CIRNAC find ways for Indigenous people to participate in and benefit from the management of northern contaminated sites.

It also recommends CIRNAC estimate the greenhouse gas emissions associated with the Giant clean up and updates its climate change risk assessments for that project, while also developing a way to track emissions for the work at Faro.

"After 20 years, there is still much work needed to reduce financial liability related to contaminated sites and to lower environmental and human health risks for current and future generations," DeMarco said in a press release.

"The government needs to take urgent action to advance socio-economic benefits, including employment opportunities, and to support reconciliation with Indigenous peoples whose lands are often affected by contaminated sites."