Krampus isn't coming to town. HE'S ALREADY HERE.

It was time for Jennifer Stakes to decorate her home for the holidays, and she had everything she needed for her front porch in Kyle, Tex.: the strands of tiny red lights, the wreath, the tree and the 6½-foot tall, animatronic, menacing horned demon. That's Krampus.

Most of her neighbors didn't know what Krampus was. Sometimes her Ring camera records the puzzled and delighted conversations of passersby who venture up to her porch for a closer look.

"I've had some people say that, 'I'm going to bring my kids by, and I'm going to tell them if they're not good, this is what's going to happen,'" says Stakes. "I'm like, okay, if that's what you want to do to your kids."

Oh, you've never heard of Krampus?

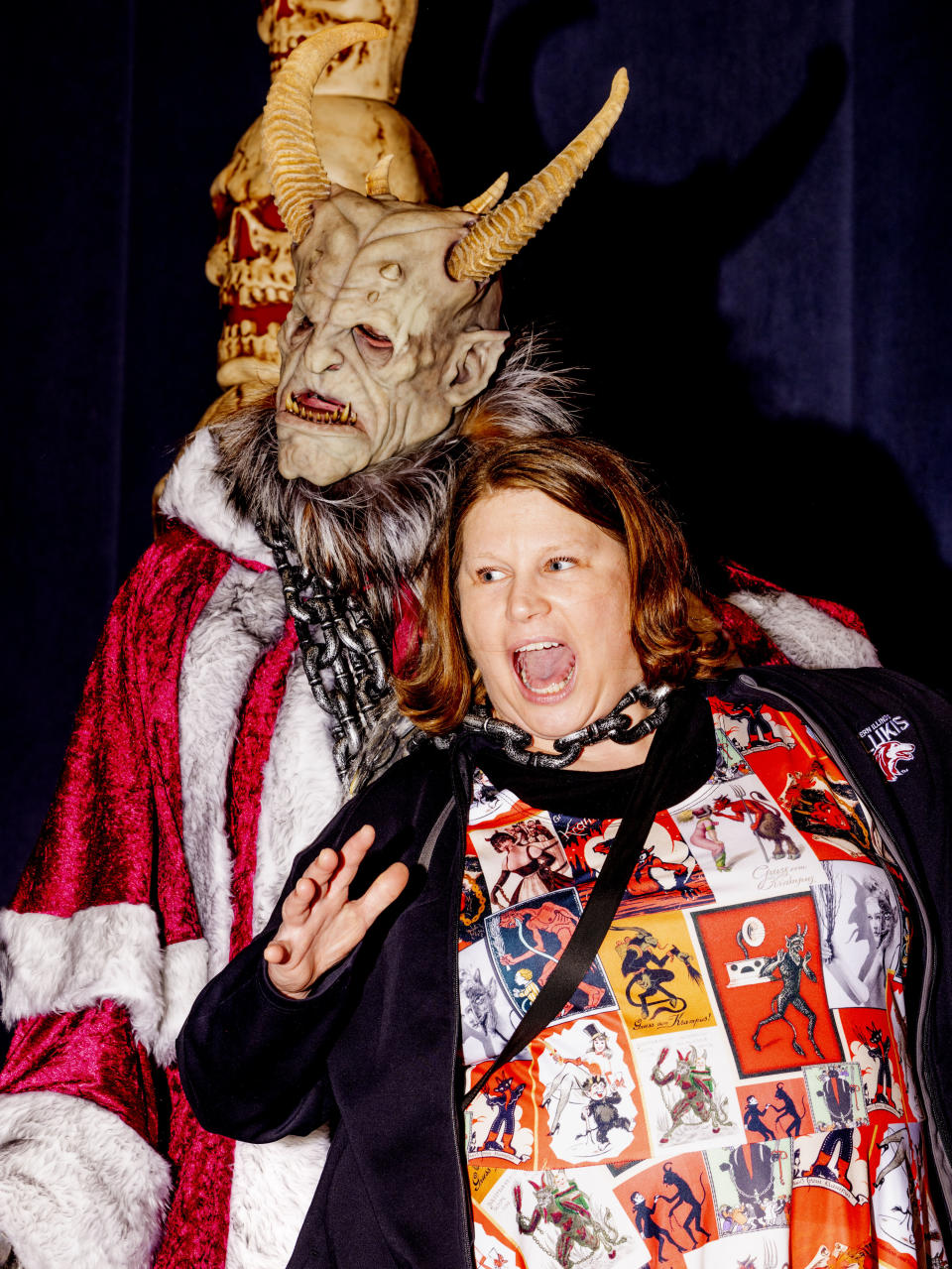

He hails from the Alpine towns of central Europe, and wears a red cloak trimmed with white fur, like Santa Claus. But underneath those robes is the body of a hairy, horned goat-like monster, with spindly, sharp fingernails and a long, creepy, Gene Simmons-esque tongue. For centuries, according to regional folklore, he's been the bad cop to Saint Nick's good cop: Jolly old Kriss Kringle doles out the presents for good boys and girls. Krampus finds the naughty ones and beats them with sticks.

In Germany, Austria, Italy and Slovakia, you'll find people dressed as Krampus parading through the streets and pretending to menace the villagers for a celebration on Dec. 5, which is known as Krampusnacht, or Krampus Night. But in recent years, you may have seen Krampus stateside, too. He's running down the streets of Los Angeles, or Chicago, or even Birmingham, Ala. Or he's on your friend's ugly Christmas sweater, or the label of your craft beer (a Vancouver brewery's Krampus abbey dubbel is toffee-colored and pairs well with red meat).

Or you may see Krampus in a Christmas haunted house. Maybe you didn't know those existed, either.

You'd better watch out. You'd better not cry. Because Krampus isn't coming to a town near you - chances are, he's already there.

As more Americans learn about this child-punishing folkloric figure - an antihero, of sorts - they can't get enough of him.

Krampus "helps balance the Mariah Carey and the Hallmark Channel," says Jason Swarr. "It gives us a little bit of that spooky, that fun, that mysterious, that dark side of things. And we're still celebrating the purity of Christmas."

Swarr is one of the organizers of "A Christmas to Dismember," a Mesa, Ariz., holiday horror convention for which the centerpiece is an opportunity to take Santa-style photos sitting on Krampus's lap. Hundreds of people lined up this past weekend - some in matching sweaters, hoping to use the image in their Christmas cards.

Swarr has taken some turns in the Krampus suit himself.

Occasionally, he'd get "a dad or mom who'd come up and say, 'Hey, my kid, whew, he has been horrible this year. Can you scare him?'" He would always comply. "That's when you get his name, you get what he's done bad, and the kid's like, 'Wait, how do you know this?'"

But he'd never take it too far.

"I get less tears than Santa does," Swarr says. "I promise you."

There has always been a dark undercurrent to The Most Wonderful Time of the Year. When Andy Williams sang of those "Scary ghost stories and tales of the glories of Christmases long, long ago," he wasn't just talking about the spirits that visit Ebenezer Scrooge. Krampus is just one of a whole array of Christmas bad guys in Europe with pagan origins. There's also Frau Perchta, a witch who slits the bellies of Bavarian bad kids and stuffs their corpses with straw. Or Mari Lwyd, an anthropomorphic horse skull who goes door to door terrorizing the children of Wales. Or Gryla, an Icelandic ogre who, with her fearsome Yule Cat, rounds up the naughty children and cooks them in a soup.

But unlike the rest of them, Krampus is the one who has caught on in the United States. Perhaps that's because in traditional lore, he doesn't usually kill the kids - he just hits them. He's a disciplinarian.

Also: "He just looks cool," says Michael Garcia, who runs a Krampus-themed haunted house in Austin.

The first Krampus parades in America popped up in the early 2010s, says Cory Hutcheson, who teaches folklore studies at Middle Tennessee State University. The monster's popularity really began to ascend with the 2015 holiday horror film "Krampus," mostly panned by critics, but a cult favorite among scary movie aficionados.

Interest has grown as people celebrating Christmas look for a counterweight to all the holly jolly. In an era of climate doom and political nihilism and high-definition war beamed onto our phones, there's something about Krampus that feels more authentic.

"There have been a lot of dire things happening in the world," says Hutcheson. "So Krampus just seems like a good figure to sort of be our boogeyman during the holiday retail season."

That was partly the impetus for Grant Tatum to start a Krampus group around Birmingham, Ala., in 2021.

"The idea of sort of a sugarcoated Christmas, you know, felt like it needed something more in the wake of the pandemic," he says. "We really wanted to add some texture and depth to what that holiday experience could be."

Friends from a community theater group handmade their costumes and marched in a local holiday parade, to the befuddlement of spectators.

"The next day on one of the local neighborhood Facebook groups, there were a handful of moms that started ranting and venting a little bit about why their child was given a little bundle of switches," says Tatum. "And, 'Who were the people with horns growling at my kid?'"

Some community members who had heard of the tradition quickly came to his defense. The group marched in last year's parade, too, and this year will hold their own stand-alone event at a local brewery, with performances from folk musicians.

Not all communities have been welcoming. John Hurst works behind the scenes in Seattle-area haunted houses, and he and his friends were looking for a way to extend their Halloween fun. When he discovered Krampus, he reached out to a craftsman in Austria to purchase a traditional, hand-carved mask, and in both 2020 and 2021, he and some friends dressed up and walked around Leavenworth, a Washington town that prides itself on its Bavarian-style architecture.

But after 2021′s event, a local business owner complained on social media about their presence, and in later comments, connected it to Satanism. The remarks were picked up by religious and conservative media. One story: "Washington town loses name of 'Christmas' in holiday festival, gains participation of Alpine Yule demons."

"I'm Christian," Hurst says. "But the Christian fanatics started contacting the city and threatening their jobs, threatening their livelihood. They started calling us, and getting hold of us on social media, and making death threats."

Hurst's group was not invited back the following year. They moved their event to the nearby town of Bremerton, where Krampus has been welcomed.

When Krampus crossed the pond, some aspects of his story were lost in translation.

A big difference with European Krampus is that he's often accompanied by St. Nicholas, who controls him with chains.

"Over here, we let them run free," says Hutcheson. (U-S-A! U-S-A!)

Americans have also expanded Krampus's powers and purpose. Instead of being "part of a complex of cultural practices that exist in really small communities in the Austrian Alps, we just kind of like him as: 'Oh, he can be the face of Scary Christmas,'" says Hutcheson.

Enter the Krampus haunted house.

When Garcia, the Austin haunted-house director, started learning about Krampus, he realized that haunted-house owners who aren't doing Christmas haunts are just leaving money on the table.

What emerged was "Krampus: The Fright Before Christmas," a three-part haunted attraction that has carried many storylines over the last few years, incorporating unrelated characters, such as Jack Frost, and inventing new ones, such as Belle, "the demon of the hall" (as in, the halls you deck).

Garcia's haunt offers a choose-your-own ending, with the option of naughty or nice. Naughty is an encounter with an especially fearsome Krampus, who has a hunchback, antlers and a mouth that resembles the Predator. Nice is a visit with Santa Claus - but he's a zombie.

"I was debating on having him holding up Krampus's chopped-off head," says Garcia.

Krampus merch has proliferated in recent years. There is Krampus liqueur, and all sorts of Krampus tchotchkes: stuffed animals, a "Krampus believes in you" mug, a Krampus nutcracker ($155!), "Merry Krampus" socks, and a wide assortment of ugly Christmas sweaters ("Merging so many different layers of, like, anti-Christmas Christmas together" notes Hutcheson). One parody shirt advertises a "Krampus Day Care Service." You can buy an elegant Krampus ornament for $75 at Bergdorf Goodman, or a campy one for $17 at Walmart.

"I have seen a Krampus-themed sex toy," says Hutcheson. A Google search reveals a subgenre of Krampus erotica. Something for everyone!

So are Americans, with their crass commercialism, appropriating Krampus? Hutcheson says that he's talked to a few people in Europe who find American Krampus distasteful.

"Maybe the whole thing is a bit exaggerated in America, but that doesn't bother us," emails Lillian Kutter, a member of the Bavarian Krampus group Oberpfälzer Schlossteufeln - which translates to "Upper Palatinate Castle Devils." The group, according to its website, currently has 29 active members who are available to spook your Christmas market: seven witches, six angels (four "big" and two "small"), 15 Krampuses and, of course, one "Upper Palatinate Santa Claus" to, you know, keep an eye on all those Krampuses.

Related Content

Facing pressure in India, Netflix and Amazon back down on daring films

What home schooling hides: A boy tortured and starved by his stepmom

Defending his 2020 fraud claims, Trump turns to fringe Jan. 6 theories