The emotional toll of covering climate change in the Trump era

I never found covering climate change to be difficult on an emotional level until two years ago. When I became a father.

Suddenly, projections of temperature changes in 2050 were more real. Where I used to be able to dismiss them as time periods when I wouldn't be around anymore, or be old enough not to care so much, now, those years were a pertinent reality.

Now, there's this adorable creature, full of hope, joy, and temper tantrums, who has no idea how screwed up his future might be due to decisions we're making today.

SEE ALSO: Prominent climate-denying politician gets schooled by science, again

Since then, I've doubled down on the beat, with grit and determination. But then came November. The election of Donald J. Trump sent me into a temporary tailspin.

What does this mean for my son's future, and what does this mean for my profession right now?

In short: Nothing good.

Not only is Trump hostile to climate science findings, calling climate science a hoax and stacking his administration with hardcore climate deniers to lead top environmental agencies—including the Environmental Protection Agency—but he's also stirring up widespread anti-media sentiment, lashing out at what he sees as a "dishonest" and "fake" news industry.

So, if being a journalist sucks right now in general, being a climate reporter doubly sucks.

What changed in November wasn't just the way in which vitriolic comments on Twitter and elsewhere got even more personal and menacing. It's that there's also, now, a sense of hopelessness that's crept into my emotional core, and that of many of the sources that I talk to over the course of my reporting.

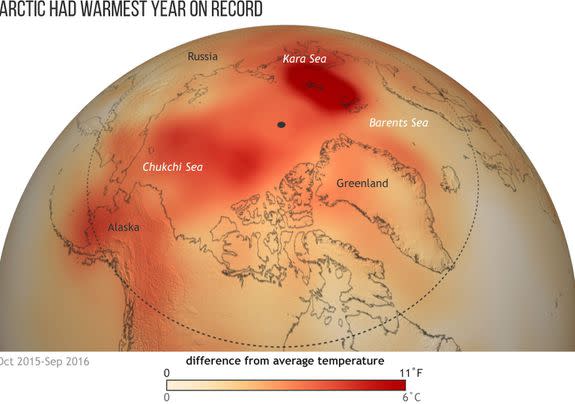

Image: noaa

The science is overwhelmingly clear in showing that we only have about another decade to start drastically reducing global greenhouse gas emissions in order to avoid widespread, damaging consequences of climate change, from rising seas swamping coastal cities to heat waves making life miserable for tens of millions of people.

Some scientists, including John Holdren, President Obama's science advisor, have argued that damaging consequences are already here, given the global coral bleaching event seen during the past two years.

Time, to the extent we have any to spare at all, is quickly running out.

This creeping sense of dread—which makes me prone to gallows humor when not simply looking at the floor, after someone asks me how climate programs will fare under Trump—makes the job that much more challenging.

It's also made me question whether I should switch reporting beats, head to another media outlet, or move on to another industry entirely.

I'm no longer as satisfied with telling myself that at the end of a workday, after delving into reports about how swiftly and expansively our planet's changing, that I at least did my part to raise public awareness on the issue, and allow people to make educated choices on the way they go about their lives in light of the information gathered here.

But when it comes to climate change, it's hard to ignore the way American voters made a terrible choice in their pick of President. More information on climate change—in the absence of, say, an active social movement—isn't going to solve this issue on its own either, since we already have enough data to act, and that's been the case for years.

Image: Spencer Platt/Getty Images

In part thanks to Trump and his allies, facts are even becoming less meaningful in today's society. It's no longer enough to just get more facts out there, and hope for the best. It's a tough reality to face as a journalist, and it's also going to take some getting used to.

I'm not alone in struggling with feelings of despair, confusion, frustration and even depression where reporting on climate change is concerned, either.

On Friday, Eric Holthaus, a fellow climate reporter who's written for Slate and the New Yorker, among others, took to Twitter to discuss his battle to come to terms with the severity of climate change at this point in time.

While I don't think I share his depth of despair, his thoughts resonated with me and thousands of others, as they were widely shared online throughout the weekend. (The entire tweetstorm is pasted below.)

I'm starting my 11th year working on climate change, including the last 4 in daily journalism. Today I went to see a counselor about it. 1/

— Eric Holthaus (@EricHolthaus) January 6, 2017

There are days where I literally can't work. I'll read a story & shut down for rest of the day. Not much helps besides exercise & time. 3/

— Eric Holthaus (@EricHolthaus) January 6, 2017

Despair is natural when there's objective evidence of a shared existential problem we're not addressing adequately. You feel alone. 5/

— Eric Holthaus (@EricHolthaus) January 6, 2017

But what the hell am I supposed to do? Write another blog post? Our secretary of state is the fucking Exxon CEO. 7/

— Eric Holthaus (@EricHolthaus) January 6, 2017

We don't deserve this planet. There are (many) days when I think it would be better off without us. <cue climate denier trolls> 9/

— Eric Holthaus (@EricHolthaus) January 6, 2017

For Eric, humanity's collective emotional response to climate change is an important story that will help determine whether and how we will solve the problem.

Will we confront and overcome the "deep despair"? Or will we succumb to it, conclude that "we're fucked," sit back, and watch the world burn? More and more, it appears the "we're fucked" argument—and the fundamental nihilism that fuels it—is winning.

I don't have an answer for where to go from here. That's why I'm in counseling. But part of the answer is: don't be afraid to talk. 15/15

— Eric Holthaus (@EricHolthaus) January 6, 2017

I'm of the faith that we'll solve this in the end. It's just going to be a rougher, more circuitous ride than anyone had previously thought, or that it should be. There are more positive than negative signs, already (particularly: the rapid adoption of renewables, and plummeting cost of solar and wind power).

For Mashable readers, I'm channeling any distress into a renewed determination to report the hell out of this issue—including stories about the suppression of climate science within the federal bureaucracy, and cuts to our ability to foresee the climate change consequences that may lie ahead.

Just as most people do, reporters respond to the emotional toll of climate change differently.

Whereas Eric is seeing a counselor to cope with his struggle—a totally legitimate and sometimes necessary response—I'm reading up on encrypted email, and preparing myself for whistleblowers to emerge with tales of how the Trump administration is gutting climate science and policy.

In other words, I'm preparing for the worst, and hoping for the best. But I have no illusions that this is easy. I agree with Eric: We need to talk about this openly, and confront our climate change-related emotions head on.

Mischievous smile on a frigid Sunday. #avigram

A photo posted by Andrew Freedman (@afreedman3) on Jan 9, 2017 at 11:18am PST

My son, Avi, is about to turn two. He was born during a blizzard, and now delights in watching clouds. I'm hoping to raise him as a climate nerd.

Whenever I feel a wave of outrage or negativity about what is going on, or what I fear is about to happen, I remember that my work is for him. Through reporting, and giving air and light to the facts of the matter at hand, I hope to improve the chances that the world he lives in will be as hospitable and stable as possible.

The stakes, after all, have never been higher.