Emancipation Proclamation on display in Nashville

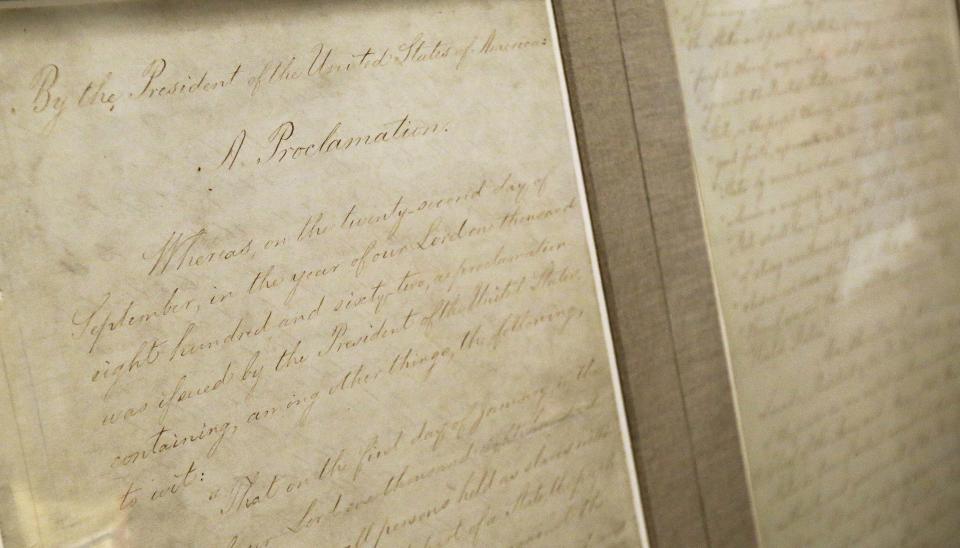

NASHVILLE, Tenn. (AP) — The original Emancipation Proclamation, a document that changed the lives of countless African-Americans during the Civil War, is on display in Nashville as the fragile historical document makes its only stop in the Southeast on a 150th anniversary tour.

The exhibit opened Tuesday — fittingly on President Abraham Lincoln's birthday — at the Tennessee State Museum and runs through Monday. It's a rare visit outside the nation's capital for the original document Lincoln signed in 1863 declaring "forever free" all slaves held in Confederate states rebelling against the Union.

Because lights are harmful to the papers, the document can only be viewed for 72 hours over the course of the six days. After Feb. 18, a replica of the Emancipation Proclamation will be on display until the exhibit ends Sept. 1.

Throngs of school children were among the first to view the exhibit on Tuesday morning. All of the approximately 18,000 reservations for visitors and school groups to visit the exhibit were taken, but more walk-in visitors were being accommodated.

Teachers at John Early Museum Magnet Middle School incorporated the exhibit in their lesson plans, such as having students create their own museum exhibits and discussions on the impact of the Emancipation Proclamation on the Civil Rights movement, said Becky Verner, an instructional designer at the Nashville middle school. She said interacting with real historical documents makes a lasting impact on students.

"They will remember this a lot longer than reading a chapter in a book," she said.

Bruce Bustard, senior curator at the National Archives where the document is kept, said Tennessee was a key battleground in the war, so he expects the "Discovering The Civil War" exhibit will draw many visitors interested in seeing some of the original documents from the conflict.

"Tennessee was an incredibly important state during the Civil War," he said. "There were more battles in Tennessee than any other state in the Union except for Virginia."

Claire Bolfing, 63, of Franklin, Tenn., said with the recent blockbuster movie about Lincoln and anniversary events commemorating Civil War battles around the South, the timing of the exhibit was perfect.

Because the Emancipation Proclamation is rarely on display, this was an opportunity she didn't want to miss. "You can see a facsimile and not truly understand what all went into creating the actual document," she said.

The exhibit is organized by topic, rather than chronologically like most Civil War museum exhibits. It emphasizes a wide range of documents, records and artifacts that have been preserved at the National Archives.

"What we are trying to do is tell you the little-known stories, and also some seldom seen documents and unusual perspectives on the war," said Bustard, during a preview of the exhibit Monday.

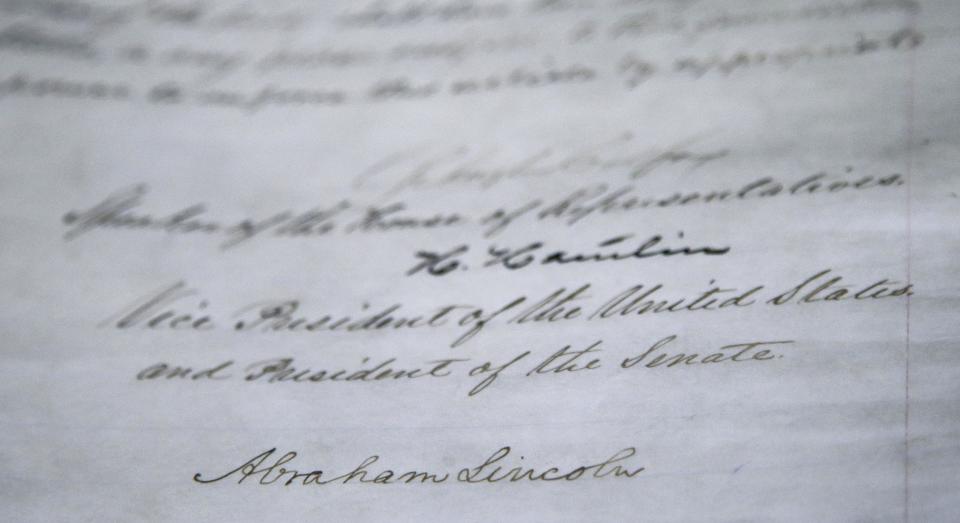

On Jan. 1, 1863, Lincoln made good on a pledge issued 100 days earlier, signing a final proclamation declaring all slaves in states in rebellion against the Union to be free.

The proclamation wouldn't end slavery outright and wasn't even enforceable at the time by Lincoln in areas under Confederate control. But the president made clear from that day forward that his forces would be fighting to put the Union back together without the institution of slavery.

Along with the original proclamation, the exhibit also displays the original signed copy of the 13th Amendment, which outlawed slavery in 1865, and an unratified 1861 amendment that would have prevented the federal government from interfering in slavery.

"We didn't want to give people the impression that the emancipation was one moment, that slavery ended from the Emancipation Proclamation for example," he said. "We wanted to get across the idea that the end of slavery was really an uneven and unsteady process, but that the United States moved a tremendous distance from 1861 and 1865."

The exhibit also features several interactive elements, including a video of reunions of Civil War troops, readings of letters sent home from the front lines and touch screens that allow visitors to explore historical documents.

The exhibit originally opened at the National Archives in 2010 and traveled to the Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn, Mich., and the Houston Museum of Natural Science in Houston before making its final stop in Nashville.

The proclamation has been rarely shown because it was badly damaged decades ago by long exposure to light. For many years it was kept at the State Department with other presidential proclamations before being transferred in 1936 to the National Archives.

___

Follow Kristin Hall on Twitter at http://twitter.com/kmhall .