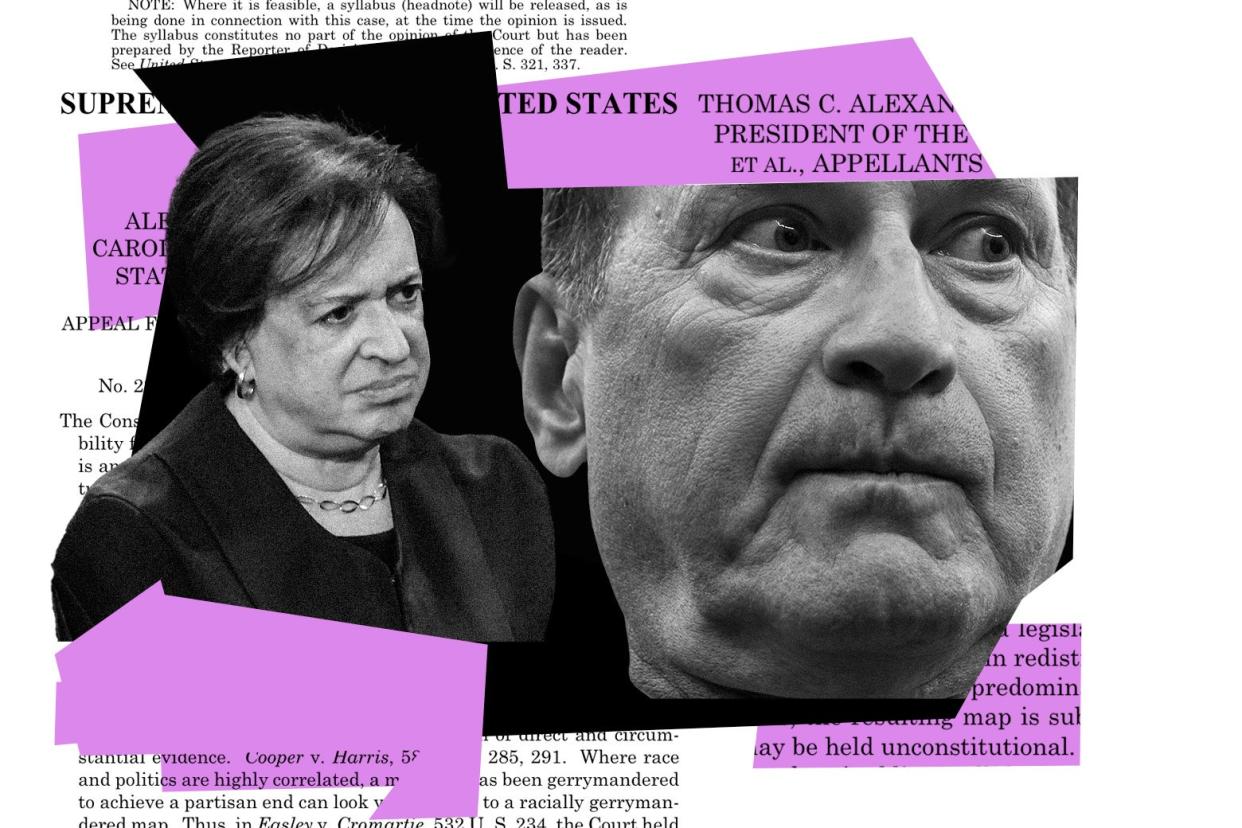

Elena Kagan Sees Exactly What Samuel Alito Is Doing

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

On Thursday, the Supreme Court dealt yet another major blow to the voting rights of Black Americans. The court’s 6–3 opinion in Alexander v. NAACP greenlighted the South Carolina Legislature’s decision to shuffle Black residents out of a competitive congressional district to shore up its Republican lean. After a lengthy hearing, a district court found that the GOP-controlled Legislature had targeted Black South Carolinians, diminishing their voting power in violation of the 14th Amendment’s equal protection clause. Now, however, SCOTUS’ conservative supermajority has absolved the Legislature of racist intent, reshaping the law to make it near impossible for voting rights advocates to win racial gerrymandering claims.

Dahlia Lithwick and Mark Joseph Stern discussed the decision in a bonus Slate Plus episode of Amicus. Their conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

To listen to the full episode of Amicus, join Slate Plus.

Dahlia Lithwick: I want to start with the fact that this is the same Justice Alito who, less than 24 hours earlier, was caught out as having flown a “Stop the Steal” Jan. 6 flag. And there he was, on the bench, handing down a decision that he penned. It was a decision that set aside mountains of actual fact-finding by the district court because Alito just decided, Well, all those facts are wrong.

Mark Joseph Stern: Exactly. Until now, the Supreme Court has reviewed those decisions on what’s called “clear error,” which is a fancy way of saying that unless the lower court really obviously messed up, you should give deference to their findings. Why? Because they were the ones sitting in the courtroom listening, witnessing, looking at the evidence, deciding the case on the very complex facts and law and math and geography that are unique to every redistricting case. Alito essentially overturned that principle of deference. He did so on the basis of what he calls the “presumption of legislative good faith”—and what Vox’s Ian Millhiser rightly calls the “presumption of white racial innocence.”

Alito says, in short, that courts should pretty much never find that state legislatures acted with racist intent, because they are owed this presumption of good faith that cuts in their favor. And he just makes up the reasons why—he’s just pulling it out of his pocket. Alito says: First, state legislators are bound by an oath to the Constitution, and we should assume they’re following that oath. Second, when we accuse state legislators of doing race-based redistricting, we’re accusing them of “offensive and demeaning conduct” that bears a “resemblance to political apartheid,” and “we should not be quick to hurl such accusations at the political branches.” Finally, he says, we should be wary of voting rights plaintiffs “who seek to transform federal courts into weapons of political warfare” through racial gerrymandering claims.

So, overall, he’s saying it really hurts the feelings of state legislators to accuse them of racial gerrymandering. It’s so mean, in fact, that courts should close their eyes to evidence of racist redistricting and give legislators a benefit of the doubt that they do not deserve and have not earned—all to ensure that the actual victims of their handiwork, the plaintiffs who are bringing this case, cannot cynically manipulate the courts into a tool of political warfare to win more Democratic representation in Congress.

I’m reminded of Alito’s presumption of bad faith for every federal prosecutor in the Trump immunity case. Of course, every single federal prosecutor is a completely feral, malfeasant gotcha guy, but state legislators are better. Why? We don’t know. It’s just the important principle that if Alito likes you, you win.

Let’s talk about what happens if Alito doesn’t like you and you happen to be an established precedent of the Supreme Court. This case should have been really easy because the Supreme Court decided a similar one in 2017: Cooper v. Harris, which involved a North Carolina congressional district. The court, which looked very different in 2017, struck down the district. And in her majority opinion, Justice Elena Kagan rejected all the garbage that Alito shoveled into the law on Thursday. She wrote that plaintiffs don’t have to present a specific kind of evidence and appeals courts should defer to district courts’ findings, not go over them with a super-skeptical eye.

Here, rather than acknowledging that he’s overturning Cooper v. Harris, Alito accuses Kagan of misreading her own opinion from just seven years ago. He says she was talking about “an imaginary version” of Cooper v. Harris—which, I cannot stress enough, is a decision that she herself wrote. It is a noxious mix of mansplaining and gaslighting for Alito to overrule this precedent without admitting it, then tell the author of the precedent that she misunderstood the meaning of the opinion that she wrote.

And Kagan’s dissent is kind of personal. You can tell when she writes those crisp, declarative sentences that she will not be told that this somehow follows on from her logic in Cooper v. Harris. And she conspicuously uses the term upside-down twice, which reads like a pretty clear dig at Alito’s flag controversy. There’s quite a visceral sense that these two are disagreeing.

I agree there’s a lot of bad blood between Alito and Kagan in these dueling opinions. Kagan sounds furious and offended, and rightly so. She is seeing her own precedent—which itself was built on decades of earlier precedent—so cavalierly and dishonestly reversed.

Sometimes when you’re in dissent, you try to make the best of the majority opinion: You can suggest that there are still ways around the new blockade, other approaches or theories or methods that might get around the majority’s roadblock. But here, Kagan gives it to us straight. As she puts it, the majority tells states to “go right ahead” and draw racial gerrymanders because “it will be easy enough to cover your tracks in the end.” If this is now the law, there is really no law against racial gerrymandering. The equal protection clause has been gutted. The post–Civil War amendments no longer have any meaningful application to racial gerrymandering.