On the elegance and wry observations of Jeffrey Smart, one of Australia's favourite painters

Review: Jeffrey Smart, National Gallery of Australia

Although I never met him, Jeffrey Smart (1921-2013) was my first art teacher. As “Phideas” on the ABC Radio’s Argonauts program he told stories of art and artists, explaining ways of seeing to children across Australia.

Two things I remember from my childhood listening. The first was the marvel of the Golden Mean, the magical geometric ratio that governs the western tradition of art. The second was a story of Rembrandt who took his own path as an artist, even though that led to criticism by his peers.

After I discovered Phidias’s identity I could see the Golden Mean writ large in his carefully constructed paintings. But Rembrandt? Jeffrey Smart’s painting surfaces meticulously honour the Italian Renaissance and his composition at times has echoes of the metaphysical works of Giorgio de Chirico. They have nothing in common with Rembrandt’s painterly approach.

But that wasn’t the point of the story. Smart was speaking in Sydney in about 1960, a time and place when artists were expected to be hard drinking heterosexual men performing painterly abstraction. Smart was not a part of that culture. He had a lifelong allegiance to the classical forms of the Italian quattrocento, especially the exquisite formal geometry of Piero della Francesca. His love of structure, smooth surface, fine detail and his sexuality put him at odds with Australia.

It was only later, years after he retreated to Italy, that his home country came to fully appreciate the elegance of his wry observations. In his old age, this artist once out of tune with his peers, became one of Australia’s most favoured sons.

Now, on the centenary of his birth, the National Gallery’s Deborah Hart and Rebecca Edwards have curated a thoughtful and generous reassessment linking Smart to the places and people who nourished him.

Shape, line and colour

It begins in his home town of Adelaide: a city with a well planned urban centre and (back then) a culture of Protestant conformity.

The young Smart painted buildings and industrial waste; the way light and shade makes patterns on surfaces; the contrast between clear constructed shapes and fluid humanity.

Local cinemas introduced him to Alfred Hitchcock, whose films use visual clues to imply tension. Hitchcock was famous for inserting himself as an incidental figure into his narratives. I have always wondered if that solitary of a watching man in so many of Smart’s paintings is in part a tribute to the original master of visual suspense.

Smart would only ever discuss his work in terms of their formal relationship between shape, line and colour. This insistence on formalism goes back to his early studies in Adelaide and the influence of the modernist painter Dorrit Black (1891-1951), who had returned to Adelaide after some years in France. The curators have included her House-roofs and flowers which hangs beside Smart’s early structured Seated Nude. It is easy to see the connection.

There is a sense of wanting to escape in some paintings of his Adelaide period, such as Keswick Siding. This is less so after he moved to Sydney where he found, despite his unfashionable devotion to precision and classical form, his art was accepted as being a part of the Charm School, which it was not. Living and working in Sydney, he also became greatly admired as a teacher at the National Art School and a broadcaster.

Humour and friends

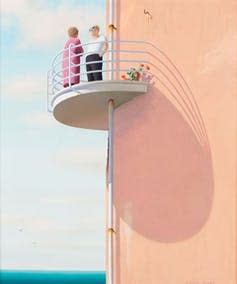

Even the most structured works of Smart’s maturity include visual jokes and a human touch. In Holiday, 1971, a relentless pattern of balconies and windows is disrupted by the small figure of a woman, lazing in the sun. He always claimed he introduced people in his paintings of buildings to give a sense of scale, an old artist’s trick. I am not sure how that works in the Portrait of Clive James, unless it was to remind the subject of his significance in the scheme of things.

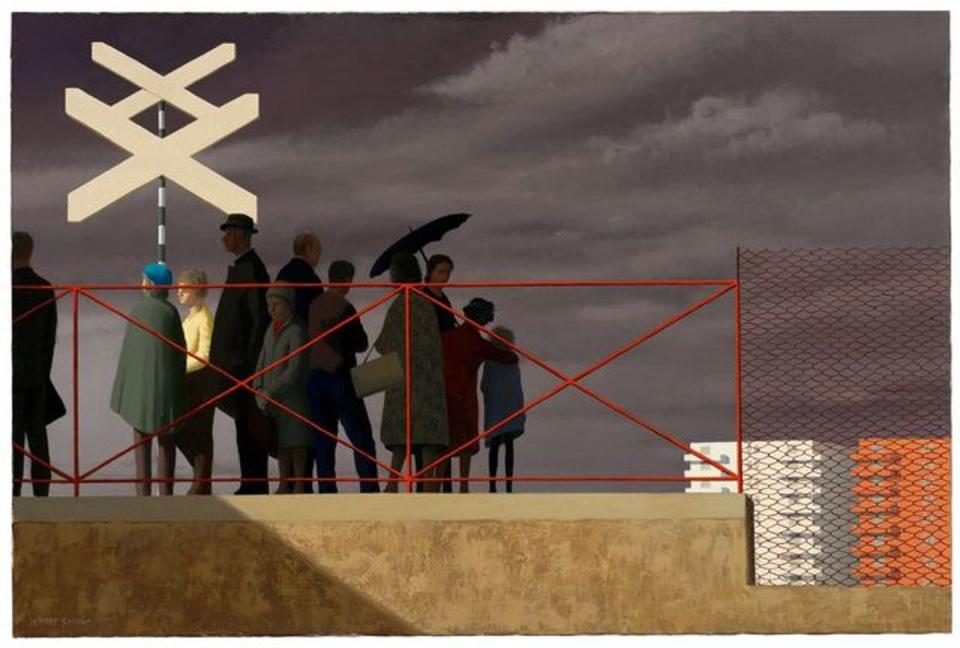

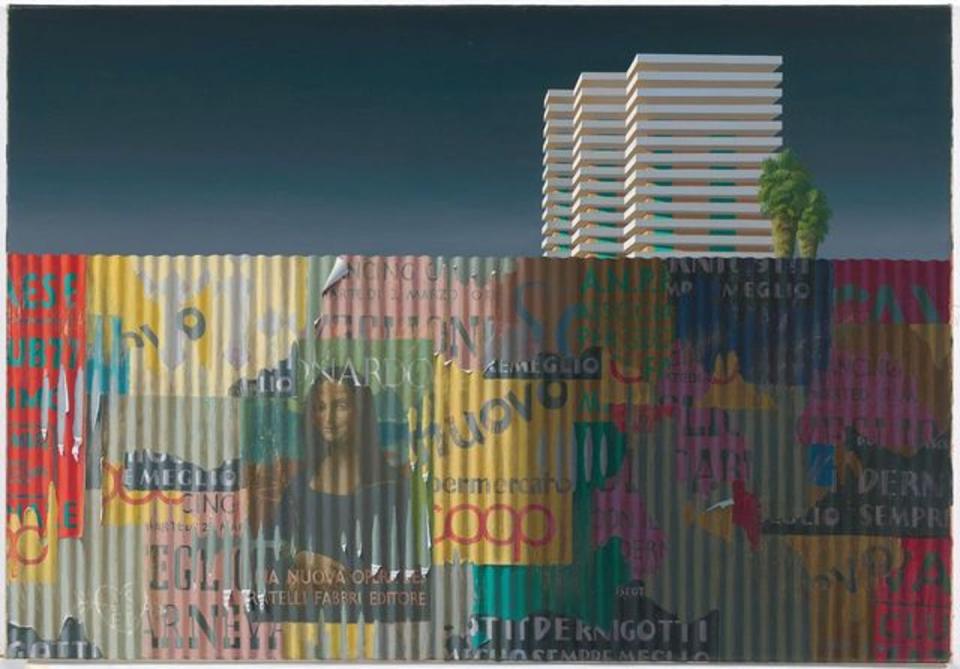

Smart’s relocation to Italy in 1963 saw a lightening of his palette, and a joyous celebration of light with the contrasting geometry of the blocky shapes of the modern world and the human scale of the old. There is a running theme of visual wit, but only for those who notice. Waiting for the train (1969-70) has echoes of compositions by Piero della Francesca, albeit in gloomy tones.

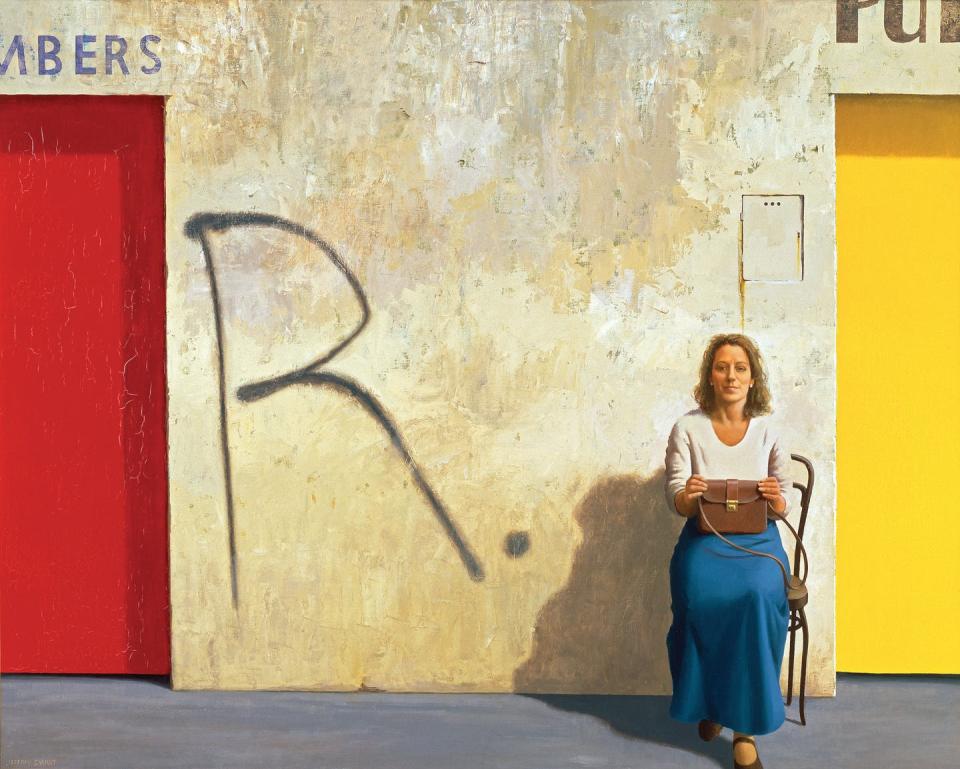

His portrait of Germaine Greer places her against an impastoed wall, a surprising rough painterly texture which could either be a comment on the subject’s character or a riposte to those who considered he was lacking in technical skill as a painter.

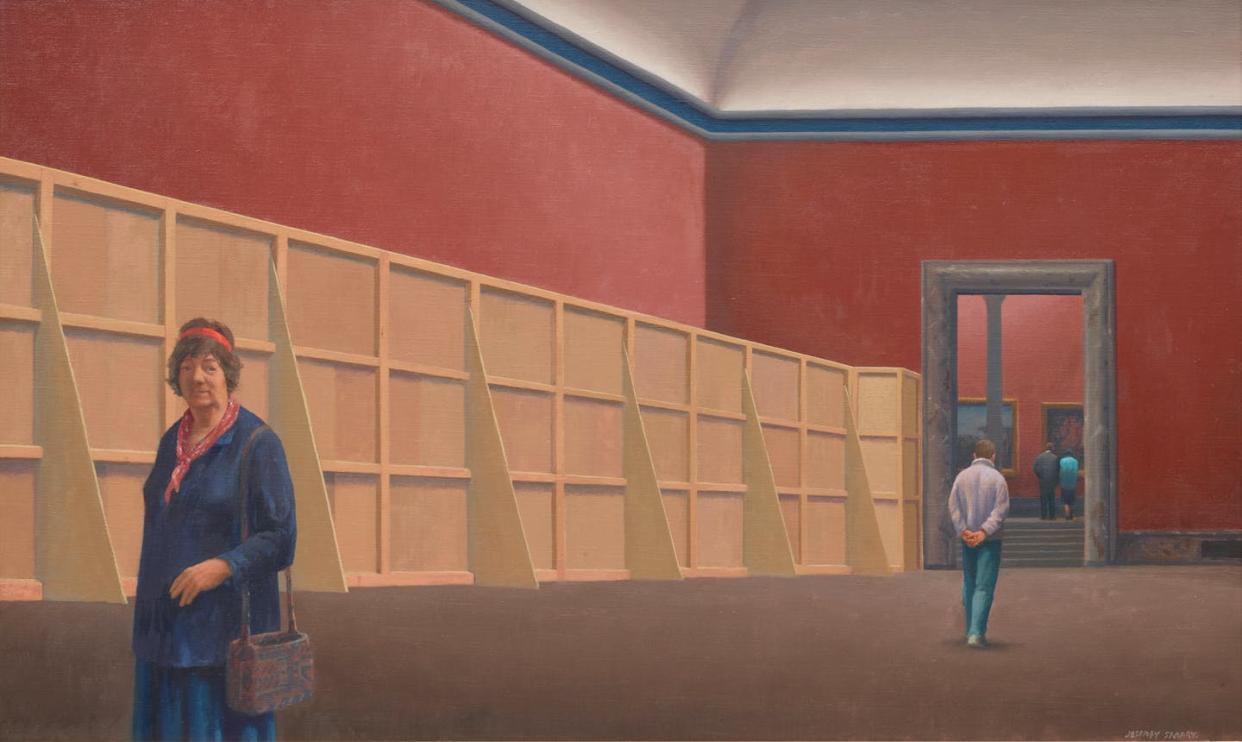

Some of the most satisfying works are Smart’s portraits of friends, and here his humour comes into play. The scholarly writer David Malouf is depicted as a workman in overalls, holding a twisting orange pipe. Margaret Olley is at the Louvre, a place she loved, but placed in front of a row of anonymous wooden screens.

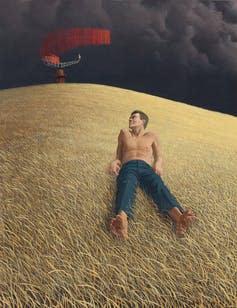

Most fascinating of all is The listeners, 1965 where a young man lies in a field of grass, overseen by a surveilling radar. The head is a portrait of Smart’s friend, the art critic Paul Haefliger who had retreated from Australia to Majorca.

It shows visual contrasts between modern technology and nature, between the golden grass, red radar and dark sky and (for those in the know) between the young body of the model and the head of the ageing Haefliger.

Smart’s portraits rarely focus on their subject. The one exception is The two-up game (Portrait of Ermes), 2008, who became Smart’s life partner in 1975. His calm face is backgrounded by the solid geometry of containers on one side and the fluidity of people playing a game of chance, on the other.

In formal terms, his image in the foreground balances the composition. This also seems to be the meaning, the reason for it all.

Jeffrey Smart is at the National Gallery of Australia until May 15 2022

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit news site dedicated to sharing ideas from academic experts.

Read more:

Joanna Mendelssohn has received funding from The Australian Research Commission