El Niño battled warm ocean temperatures during the above average 2023 hurricane season

Superheated waters in the Atlantic Ocean nurtured budding hurricanes this year like an incubator for tropical trouble that bore an impressive 20 cyclones through mid-November.

But El Niño thwarted most of their coiled fury.

Never on record had the two opposing forces of nature existed together during a hurricane season. It had always been either the storm-shredding El Niño or storm-stoking above-average water temperatures.

Scientists were eager to learn which would gain dominion over the Atlantic basin.

It may have been a tie.

Clash of titans: NOAA 2023 hurricane season forecast: We really need El Niño to form this year

Some storm experts credit El Niño, in part, for weakening the Bermuda High and anchoring its clockwise swirl of winds in the eastern Atlantic Ocean. Instead of a yawning flow of steering winds flinging hurricanes onto the U.S. coastline, the storms that formed in the runway between the Caribbean and Africa spun innocuously out to sea.

While the year was well above average in quantity of tropical cyclones, just three made landfall in the United States.

Shrinking the Bermuda High is not the typical protection offered by El Niño, which is a rending wind shear that cuts the heads off budding storms, but it worked.

“We actually lost the Bermuda High for a couple of weeks,” said Jonathan Belles, a digital meteorologist with Weather.com. “The theme this year was that storms kind of meandered around without a whole lot of direction one way or another.”

Hurricane Idalia reached wind speeds of 130 mph at its peak

Hurricane Idalia was the cruel exception.

Idalia began as a clumsy area of low pressure near the northeastern Yucatan Peninsula on Aug. 26. But it had a buffet of deeply warm waters as high as 88 degrees to feed from in the Gulf of Mexico that offered ample fuel for strengthening.

Nearing Florida’s Big Bend region, it mustered a bout of rapid intensification that in 24 hours ratcheted wind speeds from 75 mph to 130 mph, making Idalia a formidable Category 4 hurricane.

Idalia slipped to a Cat 3 just ahead of its 7:45 a.m. landfall on Aug. 30 about 55 miles northwest of Cedar Key. It was the strongest hurricane to hit the area since 1896, and proved the most brutal of the trio of named systems to breach U.S. shores during the season that runs June 1 through Nov. 30.

“If you live in the Carolinas or southeast Florida, you’re thinking ‘What hurricane season?’” said Jeff Weber, an atmospheric scientist at the University Corporation for Atmospheric Research. “But ask the people in the Big Bend, and they will say it was devastating.”

More: El Niño in Florida can mean rainy, cool dry season, but climate change may blunt the chill

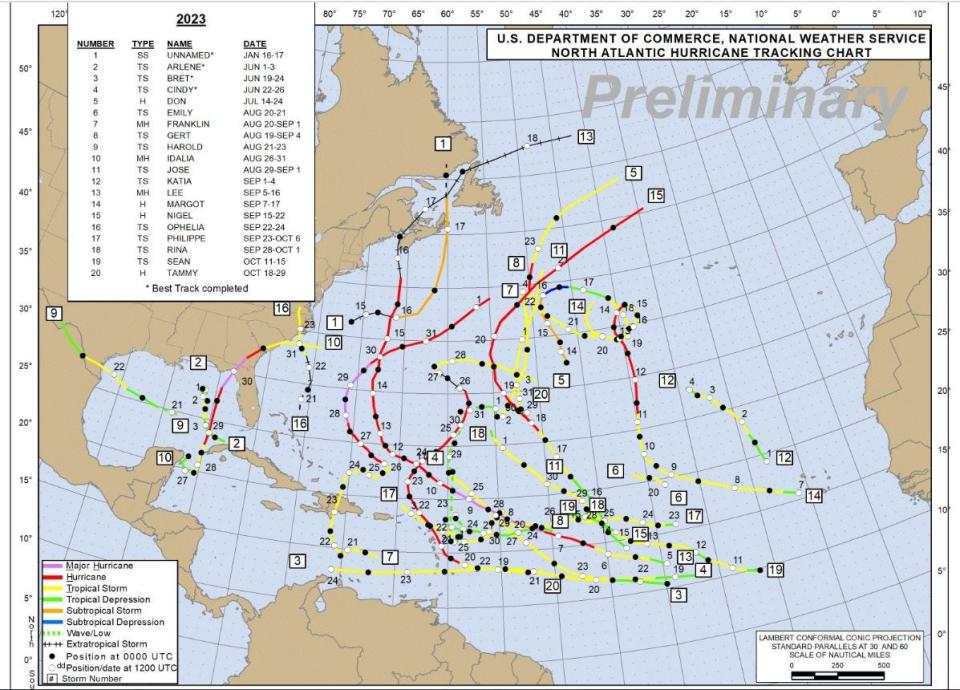

The 20 storms this year, which include an unnamed subtropical storm that formed in mid-January, ties 1933 for the fourth highest on record.

It’s evidence to Colorado State University hurricane expert Phil Klotzbach that the warm water in the Atlantic Ocean, Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico overpowered the cyclone-shredding El Niño.

“Twenty storms in an El Niño year is nuts,” Klotzbach said. “The warm Atlantic won, especially when you look at the large scale because the wind shear was quite low.”

At the same time, however, El Niño caused the Bermuda High to be “insanely” weak, Klotzbach said, which promotes recurving storms instead of ones that are pushed west.

“It really limited the impact, even though there were quite a few storms,” Klotzbach said.

Harold and Ophelia also made landfall in the United States in 2023

The three storms that made landfall in the United States — tropical storms Harold (Texas, Aug. 22) and Ophelia (North Carolina, Sept. 23), and Hurricane Idalia — formed in the Gulf of Mexico or along the East Coast.

Of the 20 storms, seven were hurricanes, including three major hurricanes of Category 3 or higher. The 2023 storm names list had just two left through mid-November after using up Arlene through Tammy.

An average hurricane season as measured between 1991 and 2020, has 14 named storms and seven hurricanes. Of the hurricanes, three are Cat 3 or higher.

The season’s accumulated cyclone energy, or ACE, which is a measure of a storm’s vigor and how long it lasts, was 146. The average ACE is 123.

This was also the seventh above-average year in the tropics since 2015 with only 2022 ending near normal for hurricane activity.

Several respected seasonal hurricane forecasts that came out in the spring misjudged the 2023 season. Colorado State predicted a slightly below-average season in its April forecast. The Climate Prediction Center, part of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, forecast a near-normal season in its May report.

WeatherBell Analytics also predicted a near-normal season overall but highlighted the uncertainty in its April forecast.

“With the state of the oceans, we are in a no man’s land, awash in a sea of warmth,” the report said.

Hurricane Lee was the only Category 5 hurricane in 2023

In May, sea surface temperatures from Africa through the Caribbean and into the Gulf of Mexico were all above normal by as much as 5 degrees. Tropical waves cartwheeling off of Africa started developing ahead of schedule with tropical storms Bret and Cindy and Hurricane Don forming in the main development region in June and July.

By early August, most major forecasts had upped the stakes to predict an above-average season.

“If you would have had these types of warm sea surface temperatures without an El Niño, I would have expected a far more devastating hurricane season for the Eastern Seaboard,” Weber said.

This season’s major hurricanes were Franklin, Idalia and Lee. Franklin reached maximum sustained winds of 150 mph, a Cat 4, on Aug. 28 while it was about 420 miles west-southwest of Bermuda.

Hurricane Lee was the only Category 5 hurricane of the season, reaching sustained wind speeds of 165 mph on Sept. 8 when it was hundreds of miles east off the northern Leeward Islands.

Lee stayed well east of Florida, partly because it was being steered by the truncated Bermuda High. It made landfall as a post-tropical cyclone in New Brunswick, Canada on Sept. 16.

Klotzbach said he’s already preparing to write a research paper with colleagues about this past hurricane season and how El Niño interacted with the Atlantic's warm sea surface temperatures.

Next hurricane season, an El Niño is less likely, while the sea surface temperatures are still expected to be above average.

With just a few days remaining in the official 2023 hurricane season, the National Hurricane Center was watching one area in the Central subtropical Atlantic for possible formation. The area of low pressure had a 50% chance of becoming the season's 21st name storm as of Nov. 22. If it was named, it would be Vince.

The only other name remaining on the 2023 hurricane list is Whitney.

“I don’t think the (June 1 to Nov. 30) hurricane season as we know it will be a thing too much longer,” said Belles. “We’ll be watching the tropics all year long.”

Kimberly Miller is a veteran journalist for The Palm Beach Post, part of the USA Today Network of Florida. She covers real estate and how growth affects South Florida's environment. Subscribe to The Dirt for a weekly real estate roundup. If you have news tips, please send them to kmiller@pbpost.com. Help support our local journalism, subscribe today.

This article originally appeared on Palm Beach Post: El Niño a key player in 2023 hurricane season but not for the normal reasons