Egypt: ultraconservative Salafis gamble on charter

EL-SAF, Egypt (AP) — Police cars crammed the courtyard of a youth center in this rural town outside Cairo, where an ultraconservative Islamist party was holding a conference on the draft national constitution. The new charter, written mainly by liberals and backed by the military, would ban political parties based on religion, give women equal rights and protect the status of minority Christians.

But the police were not out to harass the Al-Nour Salafi party, as they have the Muslim Brotherhood, which is organizing a boycott of this week's referendum on the new constitution.

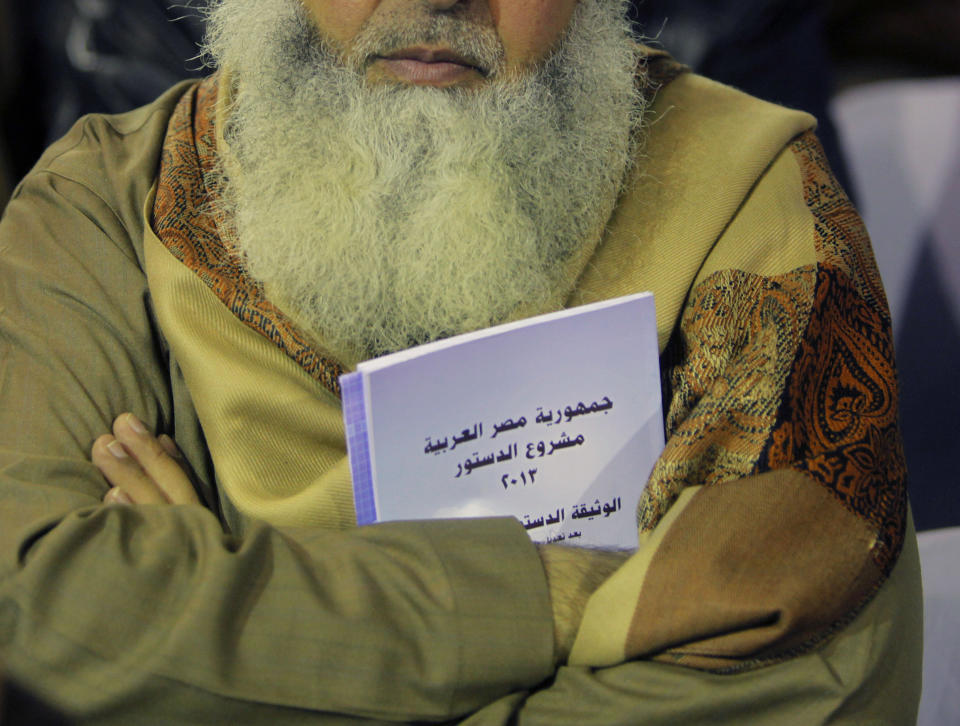

Bearded men in long, traditional robes shook hands warmly with police officers who also filled the hall to secure a lecture entitled "Know Your Constitution." And what these Islamists know about their constitution is that they will support it — even if some may privately dislike it.

The conference, held to rally support for the charter, highlights a striking alliance that has emerged since the military toppled Islamist President Mohammed Morsi and his democratically elected government last summer. Both the military-backed authorities and the Al-Nour party appear to be benefiting from it, despite the awkwardness.

The authorities get a seal of approval from a popular Islamist party for a constitution drafted by a liberal-dominated committee they appointed. The charter, despite its progressive ambitions, accords the military special status by allowing it to select its own candidate for the job of defense minister and empowering it to bring civilians before military tribunals.

And Al-Nour secures a safe spot for itself — and perhaps even a hand in power — amid a relentless media campaign against Islamist groups and an intensive crackdown has left thousands of Morsi's supporters behind bars or killed during violent clashes.

Statements from party leaders and senior clerics suggest they realize the government's campaign has been effective. They blame Morsi for overreaching in so badly offending non-Islamists — in part by ramming through a more religion-based constitution that was approved in a referendum boycotted by many secular voters in December 2012.

"We are currently trying to minimize the effect of practices that led to a general alienation from the Islamic project," said Yasser Burhami, an influential Salafi cleric, explaining to viewers on the group's online Youtube channel in a recent video why it is acceptable to vote for a constitution that has removed religion-based articles his group once campaigned hard for. "We must acknowledge the new reality and put goals according to the new phase."

There is irony there: during Morsi's term many blamed Salafis for radicalizing his group and insisting on more Islamic-based legislation.

Salafis advocate strict segregation of the sexes and an unbendingly literal interpretation of the Quran, saying society should mirror the way the Prophet Muhammad ruled the early Muslims in the 7th century. They say they want to turn Egypt into a pure Islamic society, implementing strict Shariah, or Islamic law. Men are known for their long beards, with the mustache shaved off — a style they say was worn by Muhammad — while the women wear the "niqab," an enveloping black robe and veil that leaves only the eyes visible.

They also reject democracy as a heresy, since it would supplant God's law with man's rulings — though they decided to set those concerns aside to enter elections after the 2011 ouster of former leader Hosni Mubarak.

The group's rallies around the country have been held in carefully selected venues, most tightly secured and well-planned. A senior security official in the southern city of Aswan, where Al-Nour had a recent rally, said police and party leaders coordinate ahead of local events to ensure limited and vetted attendance.

The Brotherhood and other Islamist groups have increasingly targeted Al-Nour during their protests, with some of its offices outside of Cairo attacked and its politicians heckled.

On Friday, dozens of supporters of the Brotherhood and the more radical Gamaa Islamiya party in the southern city of Assiut chanted against Al-Nour following the weekly prayers. "Al-Nour is a traitor and an agent for the regime. They sold out Islamic law," about 70 protesters chanted as worshippers trickled out of the mosque — until the police dispersed them with tear gas.

Authorities have been cracking down on people trying to distribute pamphlets calling for a "no" vote in the balloting to be held Tuesday and Wednesday, mostly on grounds they were representatives of the Brotherhood, which the government has declared a terrorist group. But the Brotherhood and other Islamist organizations have called for a boycott.

Founded after the 2011 revolution against Hosni Mubarak, Al-Nour party won about a quarter of the vote in the country's first parliamentary election held later that year — coming behind only the Brotherhood. It soon broke with the Brotherhood, accusing it of monopolizing power. And today Al-Nour argues that it is not a religiously-based party, but rather one with a "religious background" that focuses on social priorities such as health insurance and economic development.

"The world needs to move forward," said Ihab Mohamed Omar, a 25-year-old attending the gathering in Al-Saf, about 40 miles (60 kilometers) south of Cairo. "People who are against the constitution don't say what the solutions are."

Still, the road to Salafi support for the charter was rocky. The 50-member panel appointed by the interim military-backed president included only one Salafi representative, Bassem el-Zarqa. He said he asked the party to leave the committee after a few sessions because he felt it was too lopsided in favor of the secular members. Al-Nour nominated another representative.

Al-Nour is "the only representative of three quarters of (Egyptians who) voted for Islamist parties. They didn't record my ideas or suggestions. It was worse than any dictator," he told the AP.

El-Zarqa, who remains a party member, said the party will try to persuade its supporters to vote for the constitution. "But I think many think this constitution is much worse than the one from 2012."

Some said the group is losing support because many see it as a fig leaf for the new authorities. "It will be a decoration," said Youssri Hamad, a Salafi politician who broke away with Al-Nour during Morsi's rule. Hamad said his new Salafi party, Al-Watan, will boycott the vote, but will prepare for future elections.

Al-Nour party's backing of the military-backed government marks a return to an earlier political posture of ultraconservative Salafis, who had for long stayed out of politics and instead supported the party in power. Under Hosni Mubarak, Salafi clerics had urged their followers not to go against their leader. Some Salafi movements in Egypt discouraged their followers from joining the January 2011 uprisings.

Although highly critical of the Brotherhood's time in power, Salafi leaders recognize the Brotherhood's appeal— and have criticized the interim government's designation of the group as a terrorist organization.

"It is hard to convince the grassroots of the merits of these extremely pragmatic twists, and many believe that they stabbed the Islamist president in the back," said Ashraf Sherif, a political science lecturer at the American University in Cairo. The calculation, he said, is that even those they have upset "will still vote for them because they will prefer them to secularist parties."

Sabah Mohammed, a 47-year-old government employee who wears the veil of conservative Muslim women, said she was confident Al-Nour was ultimately true to its Islamist principles.

"They are a religious party...I know they would apply (Islamic law). They are good. I've seen nothing from them that was bad," she said, sitting at the back corner of the male-dominated gathering.

___

El Deeb reported from Cairo. Associated Press Writer Mamdouh Thabet contributed to this report from Assiut, Egypt.