Edward Burtynsky's photos are stunning — but do they move people to take environmental action?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

On the second floor of the prestigious Saatchi Gallery in West London, small circular splotches of ruby, slate and marigold fill a large framed print hanging on the wall.

Passersby from a photography group remark that it looks like the work of 19th-century Austrian painter Gustav Klimt. But it's not a Klimt. In fact, it's not even a painting.

It's an aerial photograph of salt ponds in Senegal, captured in 2019 by Canadian photographer Edward Burtynsky. Digging shallow ponds allows workers to harvest the salt, which from Burtynsky's vantage point made the Earth's surface look like a porous, multi-coloured sponge.

The Saatchi is currently devoting two floors to an exhibition entitled Burtynsky: Extraction/Abstraction, the largest of his storied career. The collection, which he calls a survey of what he's been doing for the past 40 years, features 94 large-format photographs, 13 murals and an augmented reality experience curated by Marc Mayer, the former director of the National Gallery of Canada and Musée d'art contemporain de Montréal.

Burtynsky's photographs take the audience from a waste transfer site in Scarborough, Ont., to the swirling grey swaths of a tailings pond at Wesselton Diamond Mine in South Africa, the world's fifth-largest diamond producer by volume (about 9.6 million carats a year).

Burtynsky is seen at work in Agbogbloshie Recycling Yard in Accra, Ghana, in 2017. (Nathan Otoo, courtesy of the Studio of Edward Burtynsky)

"The urgency that I've been feeling over the last decade has now hit a kind of a fever pitch," Burtynsky told CBC News.

Burtynsky, who is also showing some of his work at the Flowers Gallery in London, says he has spent more than four decades "bearing witness" to the way civilization has transformed the planet, and hopes this exhibition will "move us all to a place of positive action."

Whether or not Burtynsky has been successful in his mission, however, is uncertain. Some critics say that rather than confronting viewers with the reality of environmental destruction, his undeniably arresting photos distance them from it.

Indeed, some visitors to the Saatchi Gallery said they were more interested in the images than the sobering context.

"I'm not sure I need to know the details of whether it's in Senegal or Turkey, Chile or, you know, the Skeleton Coast or Russia," said Tony Greenwood, a self-proclaimed Burtynsky fan. "I mean, it's interesting, but to be honest with you, I prefer to just stand back and just be a bit awestruck."

A quiet kind of activism

Others think Burtynsky fulfils his brief.

"It has an impact on you from an environmental perspective that you don't get from looking at it on a small scale," said Mark Smith, an amateur photographer who visited the exhibition with his wife, Helen.

Captured by Burtynsky in 1996, this photograph shows the nickel tailings just outside of Sudbury, Ont., one of the most mineral-rich areas in the world. (© Edward Burtynsky, courtesy Flowers Gallery, London)

The exhibition, which opened last month and runs until early May, features a "process room" that houses some of Burtynsky's cameras and behind-the-scenes images of him in the field, as well as a personal journal from 1983.

In it, Burtynsky outlined what would become the thesis for his work: "We as a species are taking voraciously from nature. But my work will focus on both nature and how we take from nature; the industry and the conversion of nature into the products that we consume."

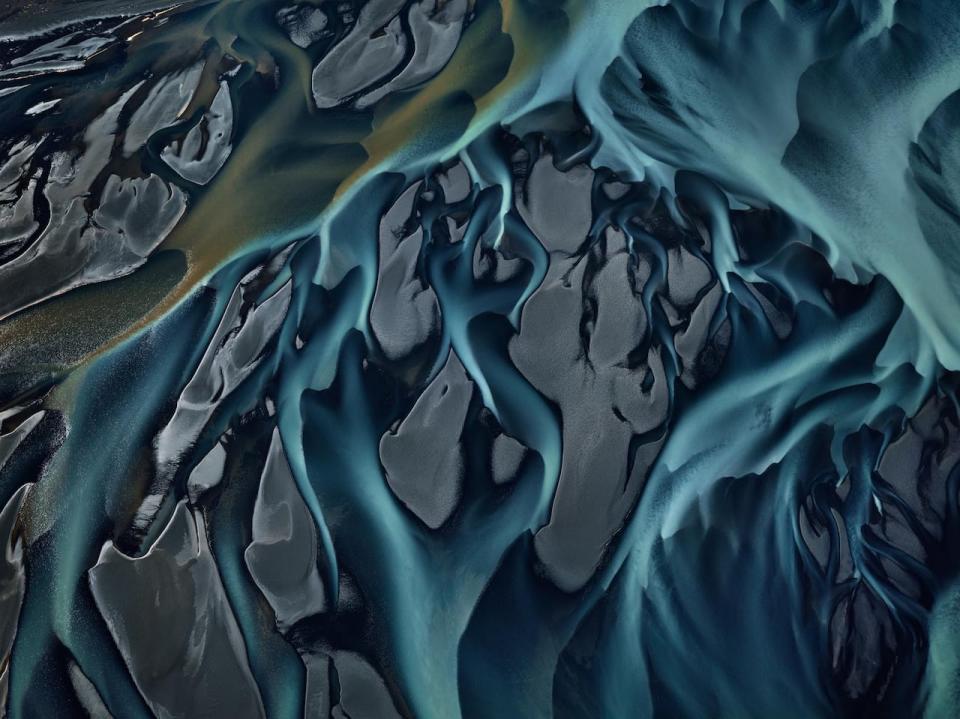

This image of the Thjorsá River in Iceland was taken in 2012. Burtynsky says it's a good time 'to really talk about biodiversity loss and talk about what's happening to the climate in amongst the other crises that we're facing.' (© Edward Burtynsky, courtesy Flowers Gallery, London)

Smith thinks Burtynsky's work is "a far better way" of getting people to think about environmental degradation than protests.

"This is reflecting back what's actually happening. This scale just makes you think, wow, there is something that needs doing here. Whereas somebody gluing themselves to the top of a train or whatever — it's just getting in my way. It's just irritating me. And I just think these people are fools."

Smith is referring to Just Stop Oil, a British environmental activist group that uses civil disobedience to demand "the U.K. government stop licensing all new oil, gas and coal projects," according to its website.

Group members have made headlines in recent years for gluing themselves to central London streets, forcing the shutdown of major roads and disrupting international sporting events such as the Wimbledon tennis championships.

"We're basically talking about the need for a revolution on so many levels at this point in our history," said Adrian Johnson, a spokesperson for Just Stop Oil. "The government, the media in general, are just not getting the message through reliably, accurately and fully enough to the general public: We are destroying our only home."

Targeting galleries

Just Stop Oil has also targeted cultural institutions. In 2022, two supporters threw tomato soup over Vincent Van Gogh's Sunflowers in London's National Gallery. The painting was unaffected, thanks to its protective glass case, but the two activists then glued themselves to the wall beneath the painting, which has left a mark from where the wall was repaired, according to Johnson.

"I was recently in the National Gallery and, to be honest, the most moving thing that I saw amongst all of the beautiful art was … the marks of where their hands were," he said.

Activists with Just Stop Oil are seen gluing their hands to the wall after throwing soup at Van Gogh's painting Sunflowers at the National Gallery in London on Oct. 14, 2022. (Just Stop Oil/Reuters)

Johnson says the reason cultural centres are a frequent focal point of disruption is because of funding from the fossil fuel industry. For example, last December, it was announced that BP had made a £50-million ($86 million Cdn) deal with the British Museum to help fund a structural redevelopment project.

In 2017, a report released by the Carbon Majors Database showed 100 fossil fuel companies have been the source of more than 70 per cent of the world's greenhouse gas emissions since 1988.

Burtynsky told The Telegraph newspaper in January that the choice many art institutions are facing between accepting funding from "big banks and other hugely profitable businesses" or going bust is a difficult one.

"At a certain point, if every artist and arts organization worldwide turns down hugely valuable funding, there's an undeniable risk of them being starved out of existence. The objections and criticisms are valid, because this [climate] crisis we're facing is real ... But perhaps those energies can be shifted," he said in an email statement to CBC News.

"These are big issues that we're facing," he said. "At this time in my life, to wade into those issues is beyond me. And it's not where my strengths lie. My strengths lie, I think, in visualizing and storytelling."

Visitors are seen inspecting Burtynsky's work at the Saatchi Gallery in London. (Lauren Sproule/CBC News)

When asked about Burtynsky's form of activism — capturing and displaying evidence of the planet's destruction — Just Stop Oil's Johnson says he supports it, but that it's "not going to be enough."

"That is why I would say there is the need and the legitimate invitation for civil disobedience, kind of like a radical flank … Changes in society for the better have shown us time and time again that you basically need to address it on all fronts."