Editorial: Paging Jesus: The Catholic Church is fighting a homeless housing project

For years, the parish of St. Mark Catholic Church in Venice has tried to help the homeless youths at Safe Place for Youth, a drop-in center where parishioners served meals and performed other volunteer work. The center and the parish hall are neighbors on a gritty stretch of Lincoln Boulevard, just around a corner from the church and its elementary school.

Yet, when it comes to the most profoundly important way the church could help homeless people — by getting them into housing — it is instead doing everything in its power to fight Lincoln Apartments, a project that would do just that. St. Mark has enlisted parishioners, school parents and the Archdiocese of Los Angeles in a campaign that, at the very least, has slowed the progress of the proposed 40-unit housing development for homeless youth and adults.

Acting on behalf of St. Mark, the archdiocese has appealed the L.A. Planning Commission's decision to approve Lincoln Apartments, which would be built on the site of Safe Place for Youth and an auto repair shop on Lincoln Boulevard. A new drop-in center would sit on the ground floor of the building, which would house about 60 residents — half of them in their late teens and early 20s, half of them chronically homeless adults. A resident who lives in the neighborhood is also challenging the Planning Commission's ruling. The L.A. City Council should reject them both and let this project go ahead.

It’s always infuriating to see community groups fighting housing for homeless people. But with homelessness in Los Angeles increasing by double-digit percentages and housing in desperately short supply, it is incomprehensible and disgraceful to see a church and the Archdiocese of Los Angeles fighting even a modest effort to get people permanently housed.

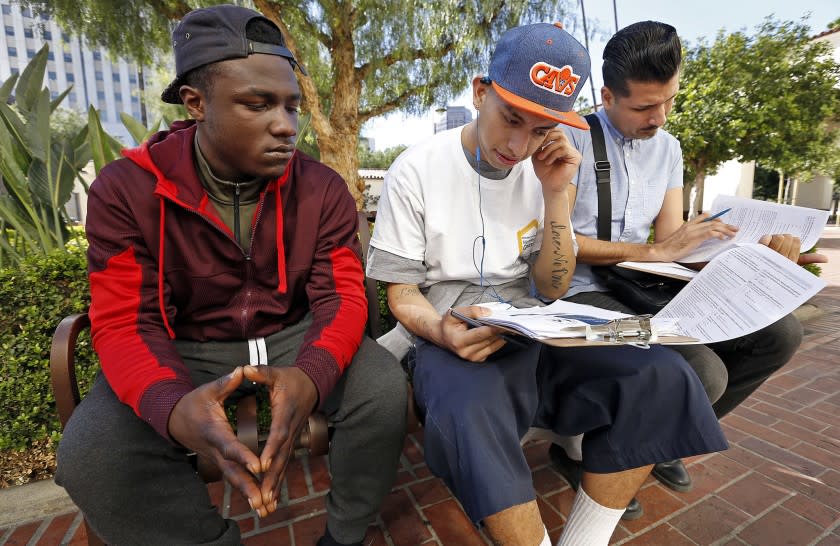

Certainly, the opposition is fierce here. Critics of the project have seized on a number of issues, but the key one is their contention that the youths who frequent the current center have harassed and threatened the neighborhood. Citing various incidents they blame on the center's clients, they say they are concerned for the safety of the children at the school around the corner from the Lincoln site.

This is a busy commercial area frequented by homeless people unrelated to the youth center, so it's unclear how many of the incidents were really caused by the youths who go there. Its executive director, Alison Hurst, says clients mainly come for food, showers and community. She acknowledged, though, that there has been “a small handful of potentially serious incidents that were handled by our staff" or the police.

Venice Community Housing, which is the developer for the project, has been giving presentations to individuals and groups for months — an extensive outreach effort that still hasn't satisfied some neighbors. The developer's executive director, Becky Dennison, has bent over backwards to make changes the community wanted, improving privacy and security. All residents will have a criminal background check, and no one will be allowed to live there if they were convicted of a crime related to the safety of children. There will be a hotline for neighbors to call if there is a problem. The staff will clean the sidewalks around the building daily — more often if needed.

Of course, the changes aren't enough for the opponents. They want 24-hour guards, even though it’s an apartment building, not a prison, and a sober-living requirement. That’s going too far. For one thing, no one residing in the neighborhood's private homes is required to be sober. For another, that runs counter to the widely accepted "housing first" model, which sees permanent housing as a necessary prerequisite to successfully treating homeless people's substance abuse or mental illness issues. Besides, any project for homeless people being funded by the city’s Proposition HHH money — which this project would receive — must adhere to housing first policies.

City Councilman Mike Bonin, who supports the project, is expected to meet with church members and Dennison Monday to see if they can all come to some agreement. Father Albert van der Woerd, the administrator of St. Mark, and archdiocesan officials should also work to quell parishioners’ and parents’ fears instead of simply capitulating to them. That may be a challenge, but it's the role that church leaders are supposed to play.

The United States Conference of Catholic Bishops has made it clear to the faithful that “decent housing is a human right.” That applies no less strongly to the homeless people who would be served by the Lincoln Apartments.