Earth's Molten Core Has Its Own Jet Stream

Scientists from the European Space Agency, studying the Earth's magnetic field from orbit, have detected a jet stream within its molten core.

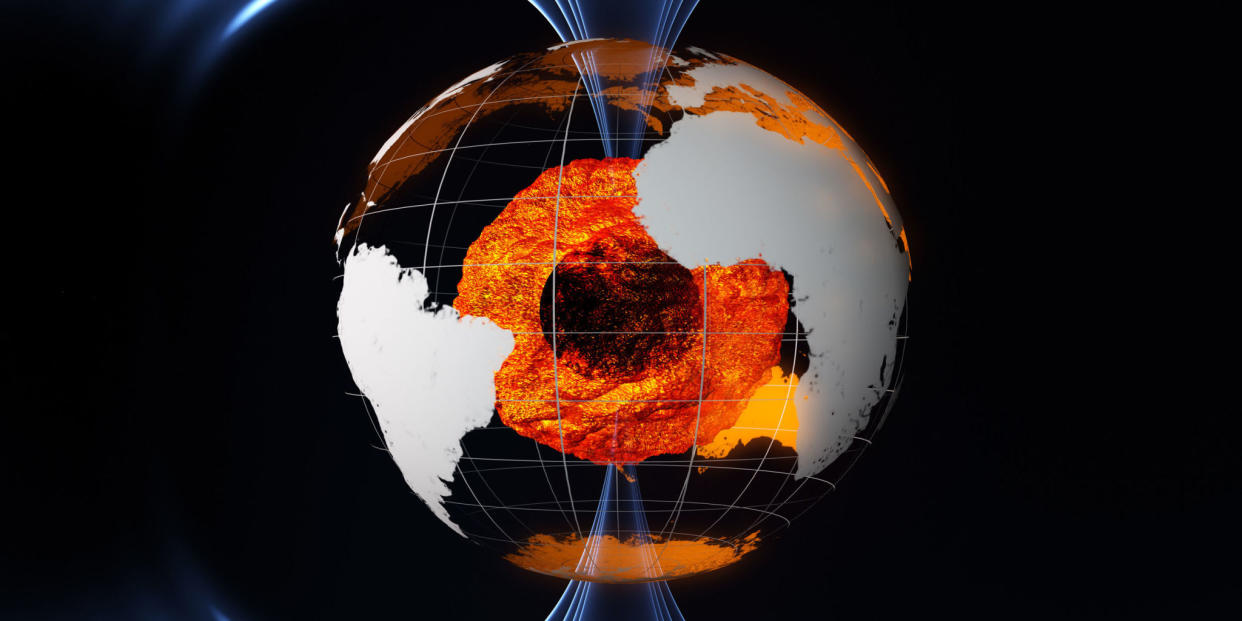

Earth's core, nearly 2,000 miles below the planet's surface, is made primarily of molten iron. The core is split into two regions: the inner core, which is completely solid, and the outer core, which is liquid.

When the liquid iron in the outer core moves around, it generates an electric current, which in turn produces a magnetic field. Because the core is impossible to reach or study directly, this magnetic field is the only window scientists have to learn more about it.

This was why in 2013, the ESA launched a trio of satellites called "Swarm" to measure tiny changes in the Earth's magnetic field. By studying those tiny changes, scientists could track corresponding changes in the movement of iron in the core.

[contentlinks align="left" textonly="false" numbered="false" headline="More%20Satellites" customtitles="Japan's%20Electric%20Whip%20Will%20Snare%20Space%20Junk%7CNASA's%20New%20Robot%20Will%20Offer%20Refueling%20in%20Space%7CSpaceX%20Wants%20to%20Launch%204,425%20Satellites%20Into%20Orbit" customimages="||" content="article.24246|article.24180|article.23937"]

When they did so, they spotted an unusual feature: a jet stream circling the outer core, similar to the one in the atmosphere. Both circle the earth around the mid-latitudes, only one lies 2,000 miles below the surface and the other sits 5 miles above it.

This core jet stream occurs because of two different layers in the outer core that meet at a boundary. When material in both layers are forced toward the boundary, either by buoyant forces or by internal magnetic fields, the material in between is squeezed and pushed outward. This creates the jet stream.

The ESA's Swarm satellites, which made this discovery, still have another year left in their scheduled mission, and may remain operational for much longer. There's still a lot to learn about the planet beneath our feet from the satellites orbiting above our heads.

Source: ESA

You Might Also Like