Doubters abound as Charlevoix couple think they found Great Lakes' oldest shipwreck

It's the oldest mystery on the Great Lakes: Whatever happened to the Griffon?

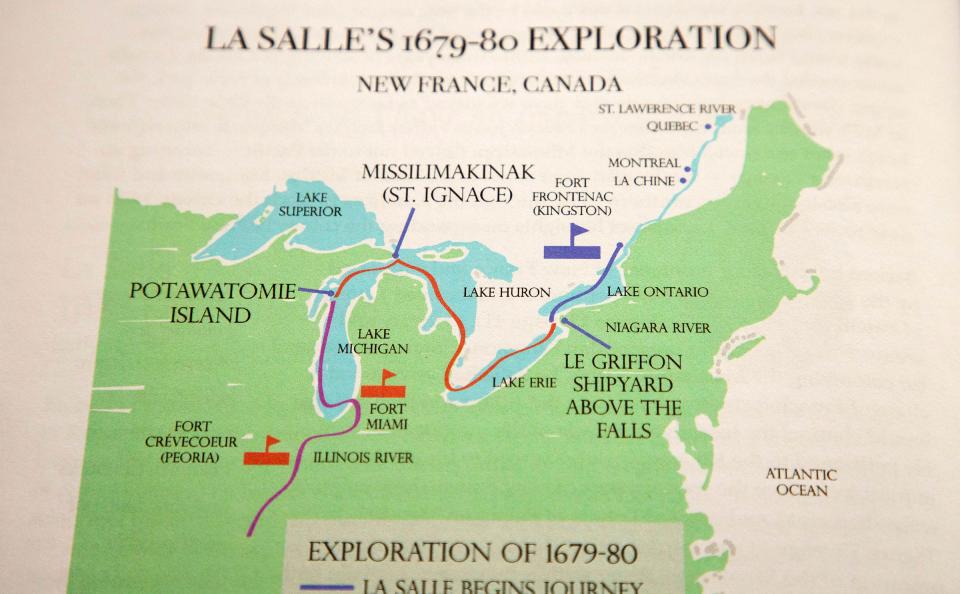

It was the first big ship to sail the Great Lakes. Loaded with furs in what's now Wisconsin, the Griffon was said to have sunk somewhere in northern Lake Michigan in 1679.

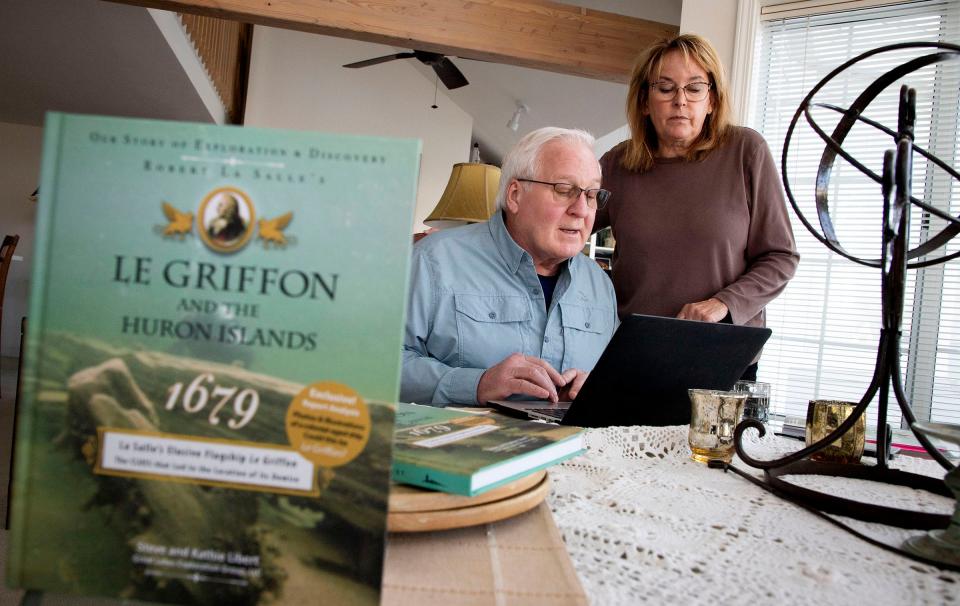

A couple in Charlevoix think they've found it. Steve and Kathie Libert, of Charlevoix, said they've spent more than 40 years seeking the answer to one of North America’s most enduring mysteries — the final resting place of the legendary Griffon. Reports by French explorers and missionaries said Native Americans told them they saw the ship go down with all hands.

The Liberts say the wreck lies near tiny, uninhabited Poverty Island, part of a chain of islands that runs southwest into Lake Michigan from Michigan's Upper Peninsula. French archeologists who visited the site at the Liberts' invitation have said they believe the couple is on to something; they even staked a claim for France for whatever wreckage turns up, Steve and Kathie Libert say in their 2021 book, "Le Griffon and the Huron Islands," published by Traverse City's Mission Point Press (about $26 in softcover and $35 in newly released hardcover).

Steve is scheduled to talk about the couple's lifelong quest and sign books at 7 p.m. Thursday at the Rochester Hills Public Library. (The program is free to the public but advance registration is required; search under calendar.rhpl.org, move the cursor to May 12 and click on "Solving the First Great Lakes Maritime Mystery.")

Skeptics abound

Prominent historians and shipwreck experts in Michigan doubt the Liberts' claim. Yet none has accompanied Steve on his dives, the couple said in an interview last week at their waterfront condominium in Charlevoix. The Liberts are well-known in northern Michigan for their decades-long campaign to find the Griffon, but this week's talk is Steve's first appearance in metro Detroit.

"I've been interested in this ship since I was 14," he said in an interview in Charlevoix last week.

"It started with a junior high teacher, talking about early European explorers. He mentioned this ship. As he walked the room, he said, 'Who knows? Maybe somebody will find that ship someday,' and he touched me on the shoulder."

From then on, Steve's obsession grew. He met Kathie in high school when he returned on crutches after a football injury and teachers asked her to carry his books. After a long courtship and college degrees, they married in 1981.

"That's when I learned about his attachment to the Griffon, and really to the Great Lakes and all shipwrecks," she said. So she joined his quest, although she is unable to dive with him because she has had a perforated eardrum since childhood.

More: Travel the Great Lakes on a floating mansion with new Viking cruise ships

More: Report: Recycling in Michigan reaches 19.3%, up 35.4% in 3 years

"I've supported the historical part of it," including the accumulation and study of an entire wall of books about French exploration of North America, 17th-century shipbuilding techniques, and just about everything ever written — from 1769 on — about the Griffon. The ship's name is sometimes converted to an English spelling — "The Griffin" — but in French, it's Le Griffon.

A lifelong dream

The Liberts have no children, so, in effect, the Griffon is their child. They pursued lifelong careers in Washington, D.C. — Steve in Naval intelligence, Kathie with her own marketing firm — but visited northern Michigan summer after summer. Now they're retired in Charlevoix, a four-hour boat ride from the dive site that they hope will someday disprove the naysayers.

At the couple’s condo, they showed the Free Press their underwater metal detectors, a wall of research books, and a sculpture of a Griffon — the French coat of arms symbol for which the ill-fated ship was named — as they made plans for Steve to dive again this summer.

They want what they’ve found preserved. They’ve vowed to take nothing at the dive site — that is, nothing but underwater photos and video. Their hope is to prove that this is the ship that went missing for 343 years.

Asked about the couple's claims, the Michigan Department of Natural Resources was quick to dismiss them. In an email, a DNR spokesman said the wreckage the Liberts have targeted can't be the Griffon:

"Our archeologist’s review of recently published media images reveals the remains of a shipwreck that features typical late 19th-century Great Lakes shipbuilding materials and methodologies, and scantlings that are entirely too large to be a French colonial vessel. The keelson structure with mast steps, paired floors and futtocks, and ceiling timbers all suggest a sailing craft, probably a schooner or schooner-barge, that was built and operated during the last half of the 1800s. Additionally, this particular shipwreck is well-known, can be clearly seen on aerial imagery internet sites, and has been visited by state authorities."

The Liberts dispute that statement, pointing to their years of studying all they could find about the construction of 17th-century French ships, much of which they summarize and illustrate in their book.

Another skeptic is Corey Adkins, communications content director for the Great Lakes Shipwreck Historical Society. The nonprofit group operates the Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum in tiny Paradise, Michigan, near the shore of Lake Superior, as well as the oldest working lighthouse on the Great Lakes, Adkins said.

The group's search team has discovered several shipwrecks, including that of the 172-foot schooner-barge Atlanta, found just last year and deemed "still beautiful after 130 years on the bottom of Lake Superior" by society Executive Director Bruce Lynn. Its museum has extensive displays of numerous shipwreck artifacts and other lore of the lakes, scale models of every conceivable type of vessel that sank, and even the restored bell of the ill-fated Edmund Fitzgerald. As for the Griffon?

"We don't really have anything on the Griffon. There have been numerous quote-unquote discoveries of the Griffon that were never proven," Adkins said. The Society's website, viewed last week, had three paragraphs about the Griffon, including the sentence: "In 2001, a famous Great Lakes shipwreck hunter, Steve Libert, claimed her wreck in northern Lake Michigan near Poverty Island." When a reporter mentioned that, Adkins said, "I think we'll be removing that today."

[ Want more news like this? Download our app for the latest ]

Whether the Liberts found the Griffon or merely stumbled on the watery wreckage of some unidentified old ship, their book and the saga of their search open a door to the fascinating earliest days of European exploration in the Great Lakes, before the founding of Detroit in 1701. At the Rochester Hills Public Library, which also serves the neighboring city of Rochester and Oakland Township, Community Relations Manager Tiffany Stozicki said she hoped that Steve Libert's talk will pique interest not only in shipwrecks but in the broader subjects of what this region was like, and who lived here, a century and a half before Michigan became a state.

Stozicki said she contacted the Liberts after a patron left her a program from the Charlevoix Public Library, where Steve Libert spoke in November.

"I'm an independent historian, and I thought our patrons would be interested," said Stozicki, who is president of the Rochester-Avon Historical Society.

"Especially going back that far, it's really hard to prove things. But we just wanted to let our community consider this mystery. People are fascinated by shipwrecks and the Great Lakes," Stozicki said.

For students of history, of any age, the Liberts' book is a good example of using primary source documents — old maps and woodcuts from centuries-old books; records left by Jesuit missionaries, who traveled through the area of the Griffon's last sightings in 1670-1672; and the diaries of expedition leader Robert Cavelier de la Salle and of the exploring party's missionary priest, Father Louis Hennepin.

Exploring with La Salle

As the book states, "In 1678, La Salle led the first party of Europeans to Niagara Falls"; and that Hennepin "was the first to publicize the grandeur of the falls in his 1679 manuscript, 'A New Discovery of a Vast Country in America.' In 1679, La Salle ordered his ship built in the wilderness above the great falls, launching Le Griffon five months later in early May. This ship was the first decked vessel to sail the upper Great Lakes of a scale and design in keeping with 17th Century shipbuilding."

La Salle named the ship Le Griffon, after the mythical creature whose body of a lion has the head and wings of an eagle. The name honored Count Frontenac, the governor of all French territories in North America, whose coat of arms featured the symbol. After La Salle's exploits in the Great Lakes, he led his followers down the Mississippi River to the Gulf of Mexico, claiming all he'd seen for France. Years later, he was shipwrecked off the coast of Texas and killed in 1687 by mutinous soldiers, according to historians cited by the Liberts.

"Kids should know, this is the guy who claimed all the land that became the Louisiana Purchase. That's a lot of our country," Steve Libert said.

The Liberts' book also uses interpretative history — color photos shot above water and below; Kathie's line drawings that depict the Griffon buffeted by the storm that sank it, as well as showing details of its likely hull design, and numerous contemporary maps of northern Lake Michigan.

The Griffon had seven cannons, according to old French records, Kathie said.

"They weren't locked down. They just sat there (on gun carriages). We're just hoping and praying, if we could find one of those in the sand somewhere, that would prove everything," she said.

Proof or not, it's certain that a storied chunk of the Great Lakes' mystery, romance and tragedy lies, somewhere, in the watery grave of Le Griffon.

Contact Bill Laitner: blaitner@freepress.com

This article originally appeared on Detroit Free Press: Griffon, oldest Great Lakes shipwreck, under Lake Michigan somewhere