Don't Cry for Notre Dame Cathedral. It Will Never Be the Same, and That's Ok

The burning of Notre Dame on April 15 felt apocalyptic, “an elemental crisis of faith and fire,” as historian Jon Meacham called it, unfolding, moreover, during Easter Week, and in a France gripped by social unrest. And it felt so even after it was announced some 15 hours after the fire began that the cathedral’s main structure, its famous stained-glass windows, and its two emblematic towers had been saved.

The orange flames and column of grey and black smoke belching into the pale Parisian sky at dusk augured some new, inevitably lesser era-the near-death of one of the most iconic buildings of western civilization. A resurrection seemed almost unimaginable.

Yes, it became clearer later that night that Notre Dame would not collapse; it stood, albeit minus its spire and its original, almost 850-year-old roof. Yes, the announced monetary pledges-with France’s luxury giants, Francois-Henri Pinault and Bernard Arnault, leading the way-quickly exceeded $1 billion. But still. It seemed to many of us who were watching that repair and reconstruction could not bring back the real Notre Dame.

“Yes we will rebuild!” exclaimed Bernard-Henri Levy, France’s renowned “public intellectual,” on April 16. “But how can you rebuild the memory of a whole country? The original, with the real age, can never be rebuilt.”

I sympathized with the sentiment. For me, the “realness” Notre Dame, which I’d visited regularly over the years since my first trip to Paris at age seven, resided more than anything in that ineffable smell of old stones perfumed with centuries of votive candle smoke, human breath, and incense. Gone for sure.

But there is comfort in reading about Notre Dame’s history. Little about this marvel of French Gothic architecture ever stood still, ever came perfectly and completely into being. What is most remarkable about it, one can argue, is the way in which it is the product of centuries of human effort and enterprise mingled with periods of neglect and even outright destruction-by “killers,” as Levy put it, referring to the wholesale vandalization of the cathedral, including the decapitating and crushing of large statues, during the French Revolution of 1789-1794. And alterations and repairs are as much part of Notre Dame’s history as the original vision for it was. A monument built from stone but ever in some sort of flux.

Notre Dame’s site itself was no immaculate tabula rasa. The Ile de la Cite is Paris’ historic nucleus and had earlier religious structures upon it-a Gallo-Roman temple dedicated to Jupiter was replaced with the advent of Christianity by an early Christian basilica, and then three more churches.

Around 1160, the then bishop of Paris, Maurice de Sully, commissioned a new, much larger church for the spot (the city’s population was swelling rapidly), and wanted it built, moreover, in the new-fangled Gothic style, demolishing the latest, Romanesque structure that stood there and recycling its parts.

The fact of the older temples likely led to suspected but long not analyzable imperfections-yes, imperfections-in the construction of Notre Dame. In 2015, a tech-savvy art historian named Andrew Tallon used lasers to create detailed 3-D scans of the cathedral (among other historic buildings) and found, for one thing, that its builders took shortcuts. The western end of the cathedral, Tallon told National Geographic in 2015, “is a total mess…a train wreck.” The interior columns don’t line up and “neither do some of the aisles,” National Geographic reported.

Why? Because “rather than removing the remains of existing structures from the site, the workers appear to have built around them.”

“Imagine the narrow medieval streets and the small wooden houses,” a Parisian friend commented a few years ago as we took a spin around the Ile de la Cite. “And this huge stone thing rising up among them.” The corner stone of the cathedral was laid in a ceremony attended by King Louis VII and Pope Alexander III in the spring of 1163 (April 25, by some accounts, exactly 846 years ago next week).

And work proceeded from then in fits and starts and phases, with changes and innovations along the way, for the better part of two centuries-unconceivable today. Several generations of Parisians witnessed the creation of Notre Dame. (The official completion date is 1345-there was no such thing as near-instant edifice gratification for the rich and mighty back then.)

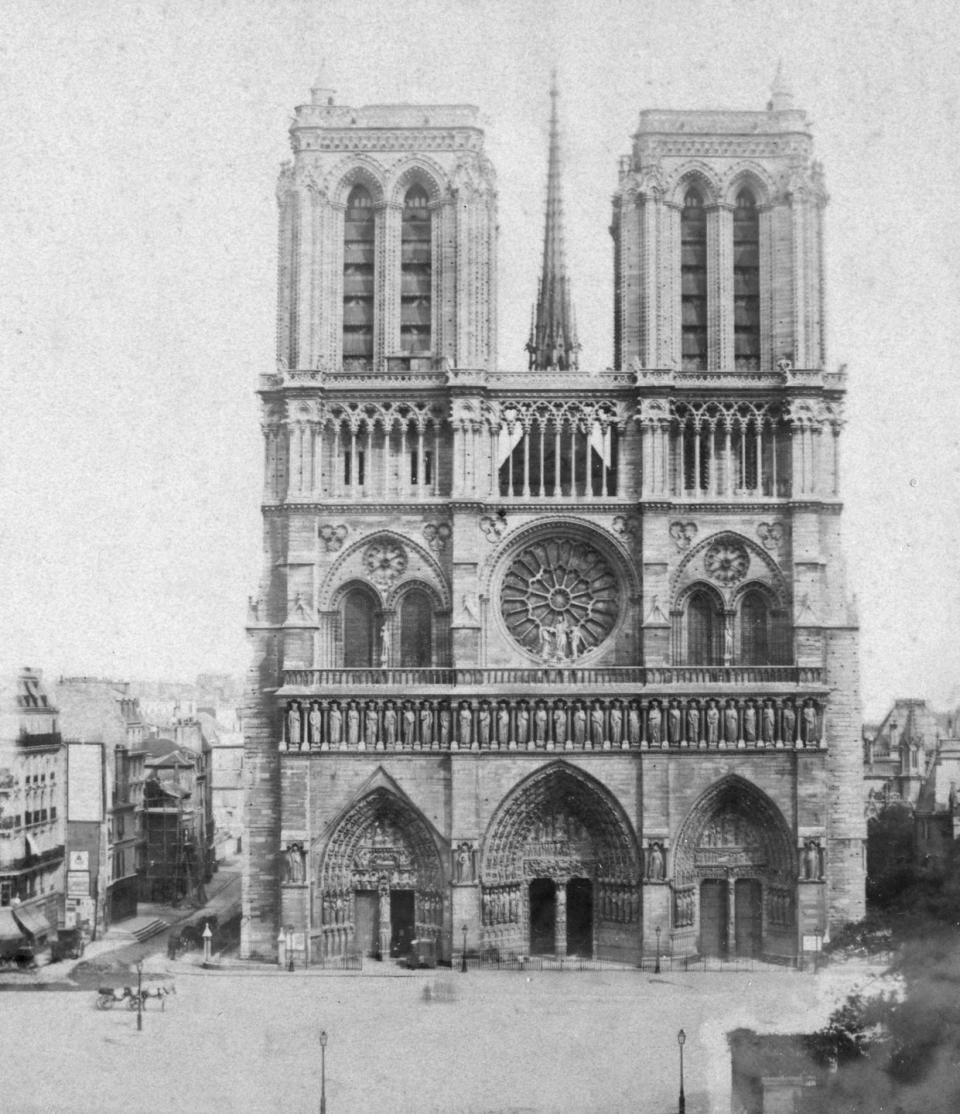

The choir was completed in 1170, the high altar in 1182. Four sections of the nave were finished in 1190. At some point thereafter, a decision was made to add transepts at the choir, where the altar is, to bring more light into the center of the church. The western façade, giving onto the parvis, the open area before the cathedral, was not completed until around 1240, and the upper gallery of the nave and the two towers on the west façade were finished between 1225 and 1250.

The transepts were subsequently remodeled; a gabled portal was added to the north transept, crowned by a rose window. This was considered such a success that it was repeated some 15 years later on the south transept. The original buttresses were deemed at some point not strong enough and were replaced by larger ones in the 14th century. And so on.

Even after “completion,” changes continued. The Gothic style fell out of favor in the Renaissance, and tapestries were installed to cover the church’s internal pillars and walls. During the reigns of the “sun king” Louis XIV and of Louis VV, alterations were made to comply more with the then fashionable classical style: the altar was rebuilt out of marble, stained glass windows were changed out for clear ones. Nothing, it seems, was ultimately sacred. In the mid 18th century, the spire, an early antecedent of the one that collapsed last week, was removed because of wind damage.

Still functioning in the early 19th-century, Notre Dame was battered and half-ruined inside, having survived, as well, its conversion to a storage warehouse. Victor Hugo’s 1831 novel, Notre Dame de Paris (translated in English as The Hunchback of Notre Dame), revived interest in the cathedral even as it drew attention to its dire condition, and it was carefully and lovingly restored over the subsequent 25 years and by two architects, Jean-Baptiste-Antoine Lassus and the then only 31-year-old Eugene Viollet-le-Duc.

They not only restored original aspects of the church, but also added new elements that they felt were in keeping with the original spirit of the place. For example, their reconstruction of the spire-the very same one that fell in the fire last week-was a taller and more ornate version of the earlier one.

I didn’t go into the cathedral my last two times in Paris, irritated-it’s a common sentiment these days-by the impossible crush of tourists (some 30,000 every day, 13 million annually) snaking their way toward the entrance along the parvis. Yet this too is no modern depredation of the original. At the turn of the 20th century, a Swiss-born novelist, poet, student of Paris, and naturalized French citizen named Blaise Cendrars evoked in one passage the crowds drawn to the Ile de la Cite by the construction of Notre Dame:

“A swarm of ordinary folk, vagabonds, pilgrims, some wealthy merchant who had taken a vow [to thank God] after eluding highwaymen, along with his employees who had like him come to work for a while as laborers, those were the people who overran the stone-mason’s yard, a veritable Zone established in the heart of the city when a cathedral was being built…with an influx of the mad, the sick, the illuminated, the devout, of preaching monks, criminals, drunkards, bourgeois, nobles surrounding the yard night and day because it is always entertaining to watch others work.”

Not only did Notre Dame survive all that. It absorbed it. As the writer Luc Sante points out in his The Other Paris, “Random members of this mob would be chosen by the stone carvers to pose for one of the myriad statues that crowd the portals and the façade. Thus the physical trace of the rabble is retained in the oldest, most august, most sanctified monument of the city.”

It is much to early to speculate about what the architects and restorers who will be commissioned now to rebuild and renovate Notre Dame after the Great Fire of 2019 will come up with. And the five-year completion date announced by President Emmanuel Macron last week might be ambitious. But there is little reason, it seems, to despair about the ultimate results, which will be just another chapter of this remarkable building’s existence and, yes, evolution.

Crowds will be gathering around it just as they did in the past-moguls with deep pockets, and people of lesser means, too; plus scientists and other experts armed with the latest technological knowhow, collectively representing a leap in human ability as impressive as the leap that back in the Middle Ages made possible the construction of an edifice of unprecedented height with, moreover, thin walls filigreed with windows-walls that have endured for 150 years short of a millennium.

As for me, I won’t be able to inhale that smell of ages in Notre Dame’s nave any longer. Tant pis, as the French say. Too bad. I’ll do my second favorite thing, though: take in Notre Dame’s rear view, my favorite, with all those flying buttresses holding up the walls so clearly visible. It is a view best appreciated from the Seine’s Pont de la Tournelle, which has often and for that very reason been my first destination in Paris.

('You Might Also Like',)