Donald Trump is the best thing to happen to global warming (seriously)

The Paris Climate Agreement was enacted Friday, and in doing so, became the fastest global U.N. agreement to go from negotiation to international law in modern history.

In an ironic twist, that quick turn of events owes a great deal to someone who actually wants to dismantle the treaty: Donald Trump.

The threat of a Trump presidency helped move world leaders to fast-track the Paris agreement, bringing it into force early enough to give the planet a better chance of staving off the worst consequences of global warming.

SEE ALSO: China climate chief to Trump: Keep the U.S. part of Paris Agreement

Most accords like this take years, sometimes decades, before they become international law—if they're even approved to begin with. So why'd this one move so quickly?

One of the most significant reasons was a substantial fear that a Trump presidency would unravel global climate action like the Paris Agreement, particularly if it was still in the fragile phase of gathering more signatories.

Sure, there were other motivations for nations such as the U.S., China, Brazil and India to ratify the agreement, which seeks to hold human-caused global warming to under 2 degrees Celsius, or 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit, through the end of the century.

But when it comes to climate change, the Republican presidential candidate seems to have motivated world leaders to come together in order to hedge their bets against a common enemy.

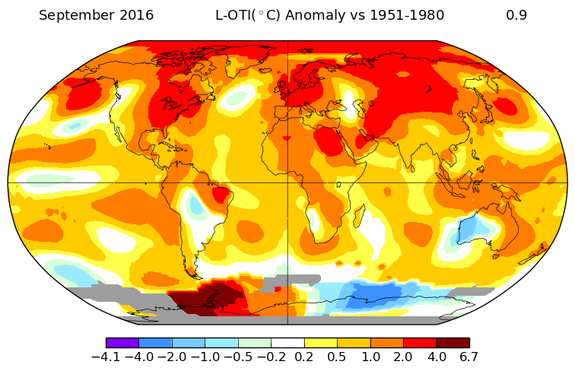

Image: nasa giss

With Paris enacted, it would be far more difficult—though not impossible—for a Trump administration to undermine the agreement by pulling the U.S. out of the U.N. talks, for example.

Now that the agreement has been entered into force, it'd take four years for the U.S. to withdraw from it, keeping it in place through the first term of the next president. However, nothing in the agreement would stop the U.S. from shirking its commitments under it, since there's no enforcement mechanism.

Trump eyes oil, gas and coal resurgence

Trump has run on the most anti-climate action platform of any candidate in more than three decades. That this is happening in what's likely to be the world's hottest year on record is striking, especially since studies have shown a rapidly closing window within which the actions of countries around the world can bend the global emissions curve downward, and get on a path toward a zero-carbon future.

During an energy speech in North Dakota in May, Trump revealed his intentions regarding the Paris Agreement in stark language:

“We’re going to cancel the Paris Climate Agreement and stop all payment of U.S. tax dollars to U.N. global warming programs," Trump said.

Image: AP

Nevermind that he can't actually "cancel" the treaty, Trump still instilled fear in global capitals where leaders are now fully on board with the need to address global warming. Just this week, for example, China's top climate negotiator scolded Trump for his proposal to torpedo the Paris treaty.

Trump's said that climate change is a hoax. He's packed his campaign advisors with climate deniers like North Dakota Rep. Kevin Cramer and energy executives like Harold Hamm. Both Cramer and Hamm favor more oil and gas development over a push toward renewable energy.

Trump's promises to revive the ailing coal industry is largely seen as an appeal to working class white voters in West Virginia and Ohio. His speeches have been peppered with distortions on wind and solar energy, which are the two fastest-growing energy sources in the U.S., saying wind turbines kill "all your birds," including eagles—a symbol of freedom—by the thousands.

Fear plus Obama, Ban Ki-moon

The fear of Trump, coupled with the passionate advocacy of two outgoing leaders—Barack Obama and U.N. Secretary General Ban Ki-moon—helped propel Paris to the finish line three years before it was expected to go into force.

President Obama and Vice President Joe Biden raised the agreement in nearly every meeting they had with international leaders this past year, as did Ban. The U.S. struck bilateral agreements with the leaders of China and India to coax them into ratifying it this year. China is the largest carbon emitter in the world, with the U.S. as the second-largest.

Image: Chris Kleponis/picture-alliance/dpa/AP Images

A huge amount of credit should go to Obama and Ban for getting this agreement into force early, but they also owe a strange debt to Trump as well.

When the treaty was negotiated in December of last year, diplomats expected it to enter into legal force in 2020 at the earliest.

Think about that — since when has the U.N. ever done something ahead of time?

The organization has many positive attributes, but nimbleness is not one of them. For example, they're still debating the cause of death of former U.N. Secretary General Dag Hammarskjöld, who died in a suspicious 1961 plane crash.

Fear of Trump, or at the very least, uncertainty about the election's outcome, played some part in setting off the mad scramble to get enough countries to legally adopt or ratify the treaty in 2016.

That dash to ratify is particularly important because of the agreement's tripwire provision, which requires at least 55 nations adding up to at least 55 percent of global emissions submit their ratification to the U.N. before it would go into effect.

So far, at least 97 nations representing 69.2 percent of emissions have done so, according to the World Resources Institute, an environmental think tank.

What the agreement will do

For the first time, the agreement commits all nations signed to it to taking actions to address global warming, though it doesn't mandate specific steps for each to take. Instead, countries have made their own commitments that, taken together, would reduce emissions enough to get the world partway toward the 2-degree Celsius target.

For example, the U.S. has pledged to cut its emissions by 26 to 28 percent below 2005 levels by 2025.

However, countries have not yet committed to reducing emissions by nearly enough to accomplish the treaty’s goals, with the world headed for at least 3.4 degrees Celsius, or 6.1 degrees Fahrenheit, by 2100, according to a UN report released Wednesday.

The next round of U.N. climate talks begin on Nov. 7 in Marrakech, Morocco. You can bet that negotiators there will be anxiously watching the U.S. election results to see if they will have to deal with a coal-spewing, recalcitrant Trump administration, or with a President Hillary Clinton, who would continue Obama's push toward a less carbon-intensive U.S. economy.