Donald Goines becomes a pop-culture star half a century after his violent death

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

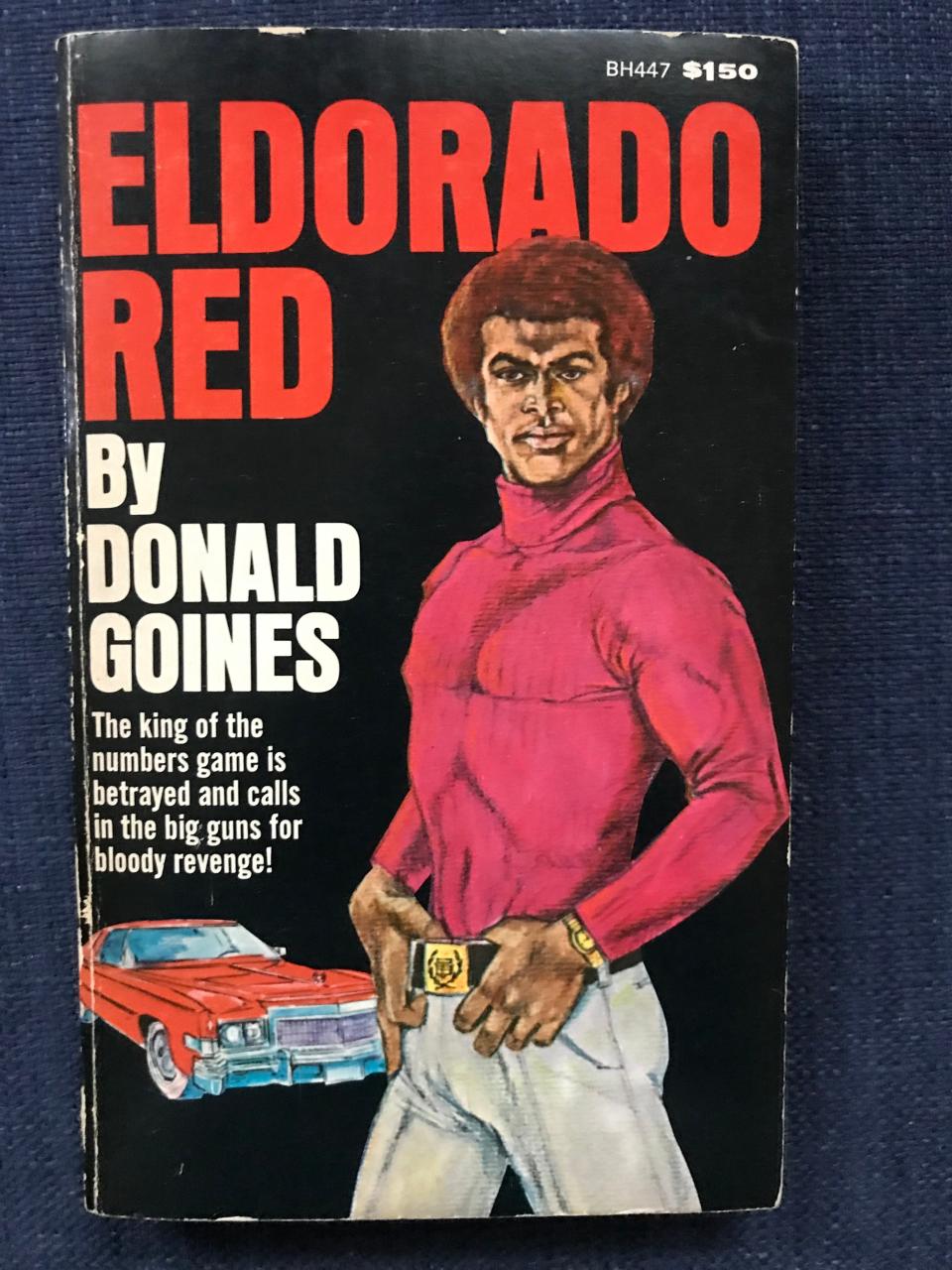

In the early 1970s, when Donald Goines was churning out his stark novels about life among Detroit gangsters, drug addicts and sex workers, the books had amateurish graphics, were printed on cheap paper and wound up for sale at bus stations and party stores because many bookstores wouldn’t carry them.

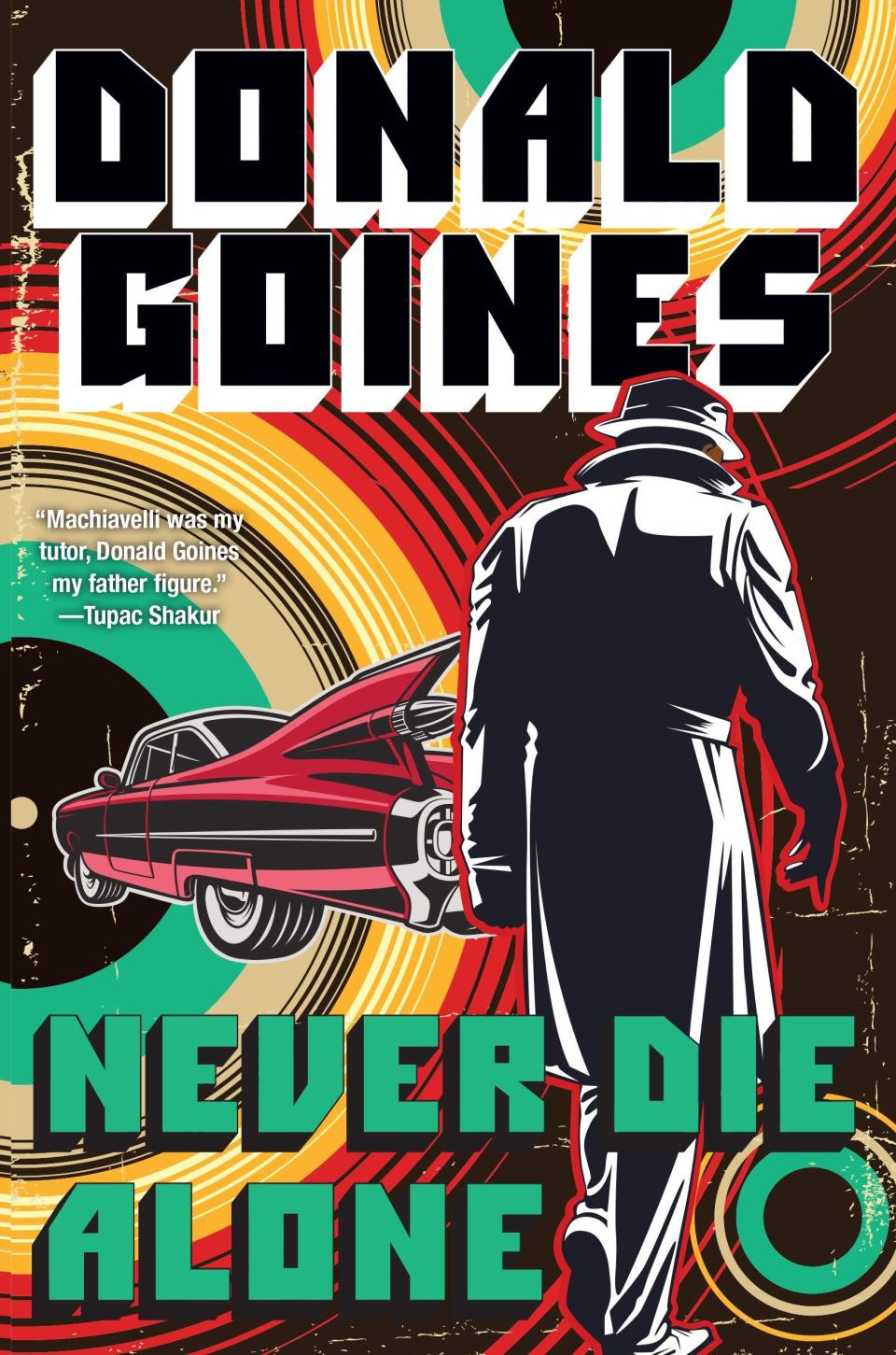

Almost a half-century after Goines’ death — in grim circumstances like a scene from one of his books — a New York publishing house is reissuing the novels with bold graphics, and readers can find them at Barnes & Noble and local libraries. Goines has become a pop-culture star whose writing is both studied in university English classes and echoed in the lyrics of rap songs.

“Machiavelli was my tutor, Donald Goines my father figure,” Tupac Shakur sang on “Tradin’ War Stories.”

Goines’ “Never Die Alone” was turned into a 2004 film starring DMX and David Arquette.

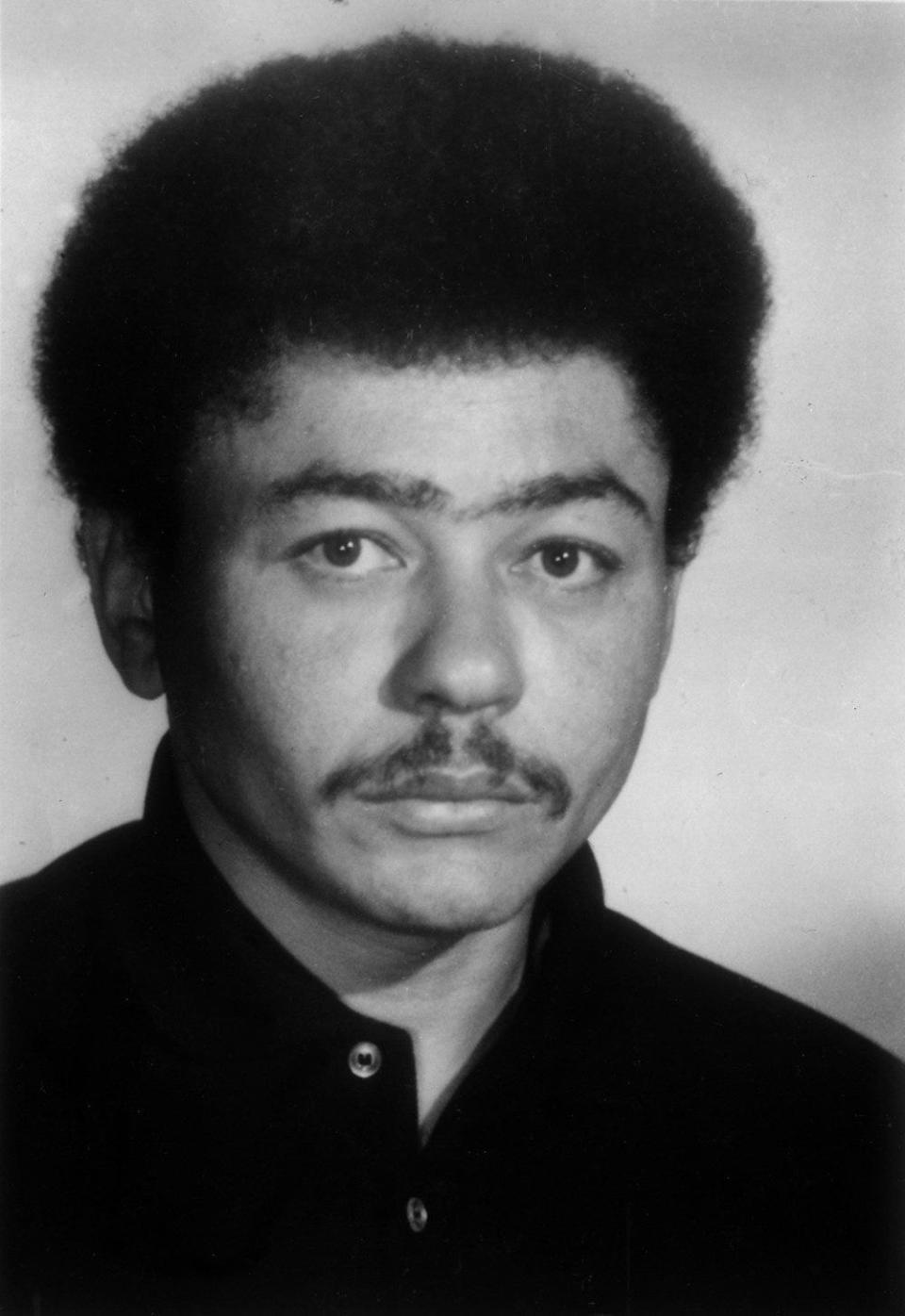

Largely unknown in white America, Goines became a bestselling author by writing about the arduous life he knew as a pimp, prisoner, con man, armed robber, heroin addict and ninth grade dropout.

His writing was rough and largely one-dimensional, but he told vivid stories, and he intensely described life at the margins of Black America. He explained mass incarceration decades before it had a name and became a popular cause. He sketched life on Hastings Street in Detroit's doomed Black Bottom neighborhood. He wrote about police brutality and retribution and gangsters, and his books, set mainly in Detroit, are filled with flamboyant violence and unromantic sex.

More: Free Press stories that made a difference in 2021

More: NBC sitcom 'American Auto' takes TV viewers into the corporate HQ of a Motor City carmaker

Fueled by heroin, Goines wrote feverishly, churning out 16 books in barely four years. Jay Wade, a longtime friend of Goines, told the Free Press in 1975 that while many heroin users nod off, Goines used the drug to get active.

“Donnie was the only one I knew who did something constructive,” Wade said. “He would go off by himself and write. It was like he had to tell people what it was really like, he had to tell people it was hell.”

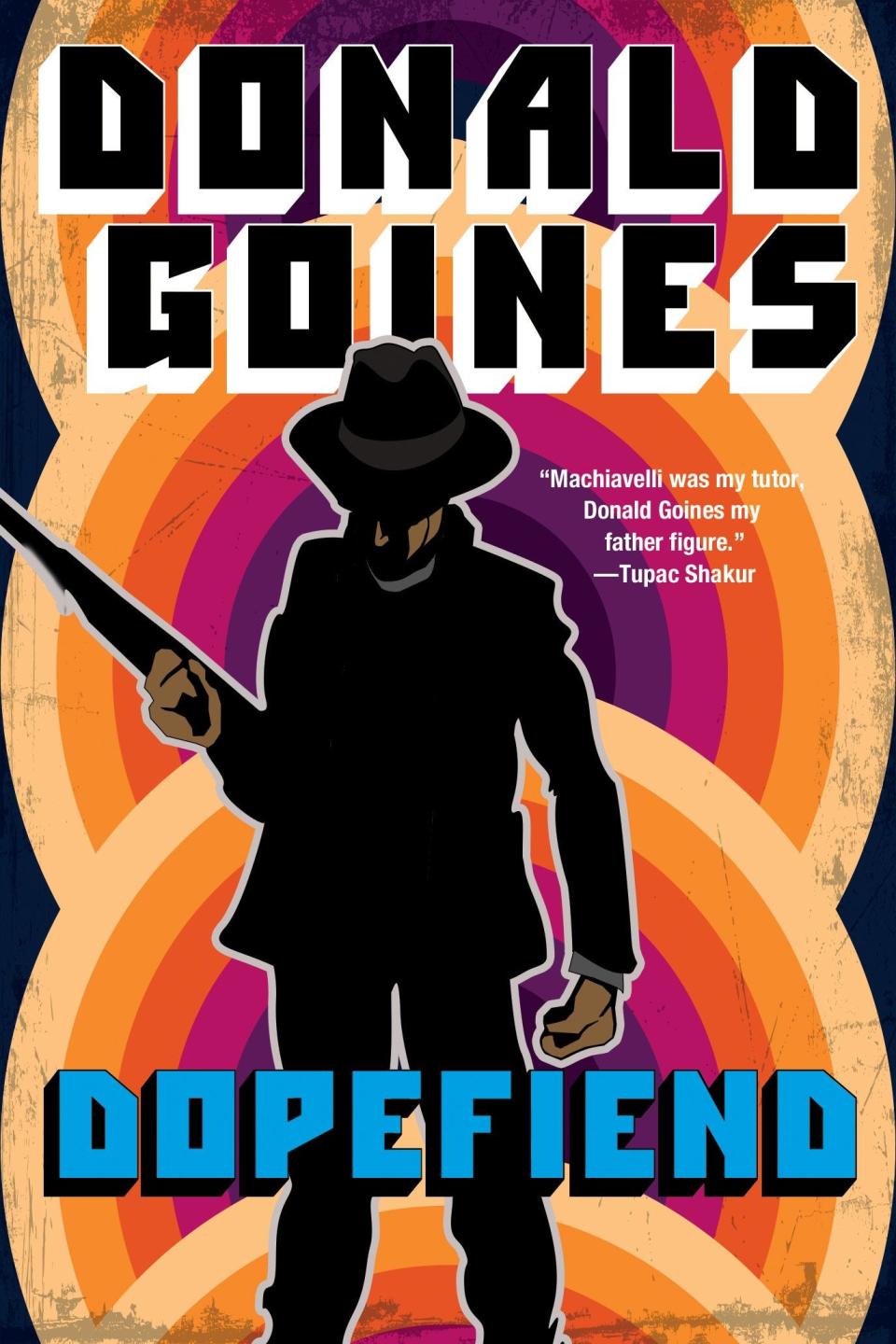

Starting with “Dopefiend” in 1971, Goines quickly attracted attention. In 2004, 30 years after his death, Goines' then-publisher told the New York Times his books were still selling more than 200,000 copies a year, and he estimated that Goines’ sales had surpassed 5 million.

The current owner of Goines’ books, Kensington Publishing, began reissuing his books in 2020, smartly repackaged with bold covers. They’re moving briskly.

“Sales of Goines’ books in 2020 were double what they were in 2019,” said Kensington’s Vida Engstrand. “It is definitely remarkable that an author who was first published — against all odds — in the 1970s would not only still be in print, but have his books regularly reissued and his sales actually increase year after year.”

Goines wrote “Dopefiend” while he served a prison sentence for attempted larceny. It’s a graphic story of heroin addiction that features a demonic pusher named Porky who abuses his strung-out customers. Goines rarely glamorized life on the streets.

“The white powder looked innocent as it lay there in the open, but it was the drug of the damned, the curse of mankind,” he wrote. To “all the dopefiends in the Detroit ghetto, heroin was slow death.”

Goines’ second book was “Whoreson,” the tale of Whoreson Jones, a successful pimp who is the son of a sex worker from Black Bottom and one of her customers. His turf is Black Bottom:

“Driving down Hastings Street was a thrill for me. The appalling deterioration of the tenements, gloomy and frightening to some people, filled me with joy. This was home to me. I didn’t know any other way of life.”

Goines wrote about hard-luck people in poor communities, but he grew up in a middle-class Catholic family in the Dequindre-Davison neighborhood in north central Detroit. In the 1940s, it was a diverse area, where his parents ran a successful dry cleaning business. His father wanted Goines to work in the family business, but Goines discovered the city’s abundant street life and begun dabbling in gambling and theft.

At 15, Goines dropped out of Pershing High, faked a birth certificate and joined the U.S. Air Force during the Korean War. In Eddie B. Allen’s “Low Road: The Life and Times of Donald Goines,” a photo of Goines in uniform shows him with a baby face, dwarfed by his uniform cap and fur-collared coat. He served in Japan and Korea, driving a truck and working as a military policeman. He also discovered prostitutes and drugs, notably heroin, and returned to Detroit a 17-year-old veteran with a habit, in a city where heroin use was becoming rampant.

“Smack would be his companion for life,” Allen wrote. “He didn’t control the habit; the habit controlled him.” In 1973, Goines wrote in a journal: “True, I really need a fix to be able to write. If I don’t fix, my mind comes to a standstill. The only thing I can think about then is where and how I can get a fix.”

Back in Detroit, Goines became a pimp. He sold marijuana. He was in and out of prison for armed robbery and bootlegging, but he systematically studied writing, completing prison classes on such subjects as grammar and transitions. Behind bars again in 1969, he got serious about being a novelist after reading “Pimp: The Story of My Life,” a memoir by a 49-year-old Black insecticide salesman and ex-convict named Iceberg Slim, a nom de plume for Chicago native Robert Beck. Goines’ mother gave him a typewriter to use in his cell.

Goines created explosive characters, like Kenyatta, the leader of a Black militant organization in Detroit who targets dirty cops and drug dealers, and Chester Hines, the small-time crook whose experiences in “White Man’s Justice, Black Man’s Grief,” illustrate inequality in the criminal justice system. In the book’s so-called “Angry Preface,” Goines zeroes in bail bondsmen, decades before they became an issue for modern-day reformers.

“Make no mistake about it, there’s big money in the bail bond business,” he writes. “Most of it is being made at the expense of poor Blacks.”

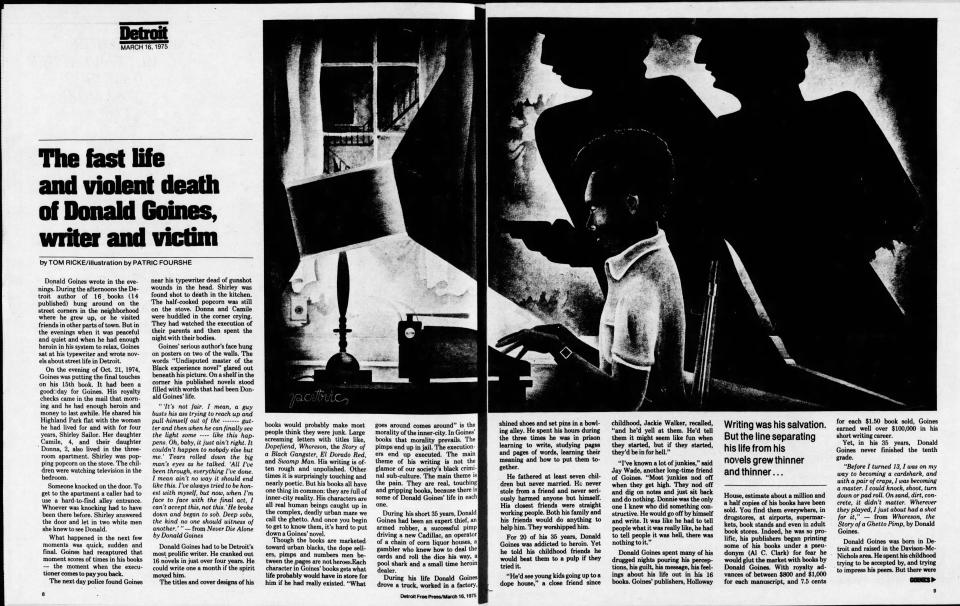

Scenes of bloody payback are a common motif in Goines’ books. On Oct. 21, 1974, two men came to his Highland Park flat, at 232 Cortland. Goines was home with his partner, Shirley Sailor, and two preschool children. Several hours later, police found the body of Goines, shot five times with a .38, twice in the head. Sailor’s body was on the kitchen floor; she was shot five times in the head and face. Popcorn sat on the stove. The children had witnessed the killing and then spent the night with the bodies.

The case was never solved, and theories for the crime range from robbery to payback for selling bad dope. At his wake, Goines lay in a casket with two of his novels. Before the lid was lowered, someone stole the books.

Bill McGraw is a retired Free Press reporter and editor.

This article originally appeared on Detroit Free Press: Donald Goines becomes pop-culture star half a century after his death