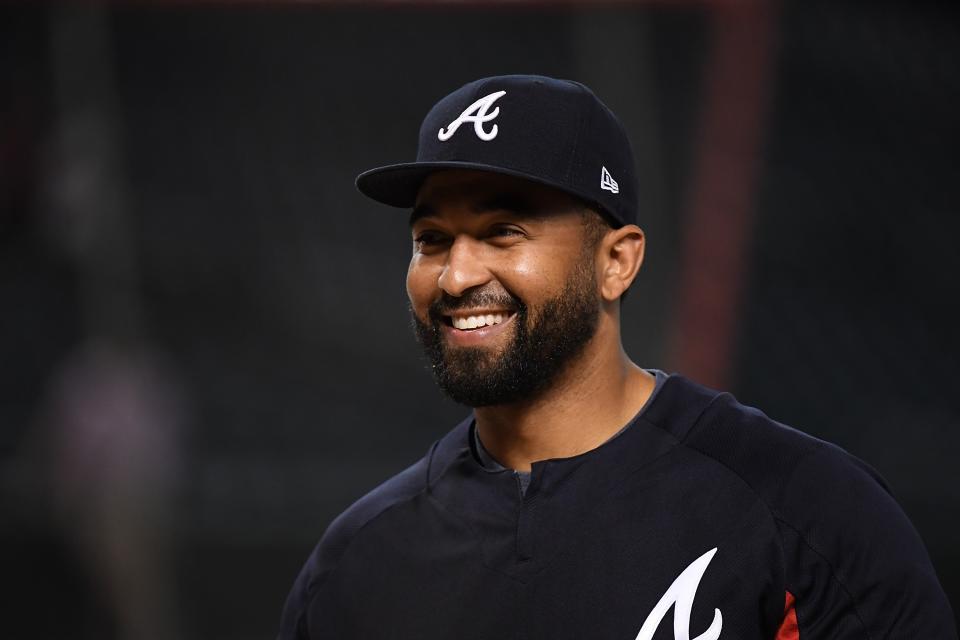

Dodgers are in even better position to get Bryce Harper after Matt Kemp trade

On days like Saturday, when the second-biggest leviathan in baseball wheedled its way into next offseason’s free agent frenzy with a touch of accounting magic, and in months like December, when the largest monster of all offered up a bag of magic beans and in return snagged the reigning National League MVP, it’s entirely fair for those sandwiched between the coasts to throw up their hands like an emoji shrug come to life and curse the sport down to its tawdry soul. This game, man. It can break your heart even in the cold of winter.

Only baseball can offer a trade of five players in which none of them really matters. When the Los Angeles Dodgers on Saturday foisted Adrian Gonzalez, Scott Kazmir, Brandon McCarthy, Charlie Culberson and some cash on the Atlanta Braves for Matt Kemp – whom the Dodgers had dumped three years ago on San Diego, which eventually dumped him on the Braves, precipitating this triangle of dumps – they were nothing but contracts, numbers, conduits to the real purpose of the deal: The Dodgers’ low-key right-swiping Bryce Harper.

That happened in the aftermath of the New York Yankees pickpocketing Giancarlo Stanton from the Miami Marlins pretty much because they can, and the roars and the cries and the caterwauls for baseball to adopt a salary cap started anew. Which didn’t register as altogether logical, seeing as these moves by the Dodgers and Yankees actually were part of plans for each to dip their payrolls beneath $200 million this season in spite of annual revenues that creep toward an estimated half-billion dollars annually.

When one remembers the complexities of baseball, it starts to make a little more sense. The goal of getting under the luxury-tax threshold of $197 million this season is to immunize both teams from severe penalties when they exceed it in future years. Make no mistake, that excess is coming. The 2017-18 offseason is both teams recognizing their ability to weaponize financial advantages going forward. The 2018-19 offseason will be them emptying both barrels.

To understand how this works, and why Saturday’s trade matters even if the players don’t, one must first get a handle on Major League Baseball’s financial strictures. The luxury tax – known throughout the game as the competitive-balance tax, or the CBT – is MLB’s first line of defense in trying to limit spending in an uncapped sport. Its floor increases slightly each season. The Dodgers have exceeded it the last five seasons. The Yankees have paid the CBT all 15 years of its current incarnation.

As such, both teams are taxed at a higher rate. By dipping beneath 2018’s $197 million mark – a number that includes the average annual value of all 25-man roster players’ contracts, the salaries of the 15 others on the 40-man roster, any money sent to other teams to facilitate trades, awards bonuses and about $13.5 million in benefits – the Dodgers and Yankees could reset their numbers from 50 percent-plus on overages to as low as 20 percent.

Perhaps it’s a bit much to say going under the CBT threshold will convince the Dodgers and Yankees to pursue Harper and Manny Machado, among dozens of other free agents in arguably the greatest class ever, come November 2018. Even if they can’t pull off the gambit, that won’t stop the thirst. Savings that can be in the tens of millions of dollars is nice. It just doesn’t stand in the way of a super-team.

Still, to see the effect, imagine the Dodgers carrying two different payrolls in the 2019 season: $250 million and $275 million. If the Dodgers can reset this year, the taxes on those salaries in 2019 would be levied as such: 20 percent for every dollar between $206 million (the new CBT threshold) and $226 million; 32 percent for every dollar between $226 million and $246 million; and 62.5 percent for every dollar above $246 million. The total tax on a $250 million payroll: $12.9 million. And for a $275 million payroll: $28.5 million.

Without getting underneath the threshold this season, the Dodgers would be paying rates of 50 percent, 62 percent and 95 percent on the overages. The $250 million payroll’s tax: $26.2 million. And the $275 million payroll’s: $49.95 million in penalties alone. On top of that, any team that exceeds the highest threshold loses 10 spots off its first-round pick in the draft the season after, another penalty that makes a number of executives with high payrolls to argue that salary-cap complaints are misguided. The penalties in place, they say, make it tantamount to a cap.

The renewed call for one coincides with the Dodgers and Yankees being two particularly well-run teams. Each has developed a number of young impact players. Both know how to play well on the margins and avoid the allure of past-their-prime stars. Nothing terrifies teams in baseball more than competent front offices with the Dodgers’ and Yankees’ revenues.

And yet nobody should forget the impetus behind a salary cap is not how individual teams spend but ensuring competitive balance exists. Seeing as the Yankees last won the World Series in 2009 and the Dodgers in 1988, well, if there’s an imbalance, it’s not doing a ton for either come October. Baseball’s variance is too great for a dynastic run the likes of the New England Patriots’ in the hard-capped NFL.

Salary caps don’t create competitive balance; they simply create the illusion of it, as if payroll would be the sole determinant of competence otherwise. Salary caps do little more than drive down money given to players and ensure it goes right into the pockets of ownership. The revenue differences between, say, the Yankees and Tampa Bay Rays? It’s dwarfed when comparing the Dallas Cowboys to the Buffalo Bills. Which means the excess money goes back to the Cowboys, enriching their owners, helping them grow into an even larger juggernaut and fomenting even more financial imbalance without bothering to share in the spoils with the players. The salary cap is no savior. It’s a tool to control the players – the reason people watch the games.

Seeing the Dodgers and Yankees trying to hold themselves to an artificial mark, then, is slightly discomfiting while entirely understandable. This is the collective bargaining agreement the union that represents the players negotiated with MLB. It makes that $197 million mark awfully alluring. The Yankees, even after trading for Stanton and signing CC Sabathia, find themselves around $180 million, with enough leeway for another move or two this winter.

That the Dodgers are two years separated from a $291 million payroll and today carry a CBT number in the $183 million-or-so range is a testament to their offseason goal. After reaching Game 7 of the World Series, the Dodgers believed they could replicate that and achieve a reset. Even though the trade with Atlanta was salary-neutral, the benefits this year are immense.

Remember, CBT payroll is based on the average annual value of contracts. While the 2018 salaries of Gonzalez, Kazmir and McCarthy add up to $47.5 million, their combined AAV is $50 million. The two years remaining on Kemp’s deal are for $43 million, and the Dodgers kicked in $4.5 million extra to cover the money difference. Kemp’s AAV, on the other hand, is $20 million. With this trade, the Dodgers kept their out-of-pocket payroll the exact same while shaving $25.5 million off their CBT number and dipping beneath the threshold.

Staying there won’t be easy. They need to fill out their bullpen. They may want some room for midseason acquisitions. The Dodgers’ desire to stay under $197 million could theoretically influence how they use their players. Even after dealing McCarthy and Kazmir – Atlanta believes McCarthy can be a good mid-rotation starter and trade asset and freed up an outfield spot for uber-prospect Ronald Acuna with Kemp, which is why the idea made sense for the Braves, too – the Dodgers boast a number of starting pitchers. With Kenta Maeda likely to make millions in easily achievable incentives as a starting pitcher, the Dodgers could move him to the bullpen with a rotation of Clayton Kershaw, Rich Hill, Alex Wood, Hyun-Jin Ryu and their choice of young starters, from Walker Buehler to Trevor Oaks to Julio Urias, who is scheduled to return from shoulder surgery.

They could deal catcher Yasmani Grandal as well, with his salary expected to be around $10 million, giving them more leeway. If it takes attaching a prospect for a team to agree to that, so be it; the Dodgers escaped the mess that was Kazmir and McCarthy’s deals – a combined 296 innings of 4.47 ERA baseball for $96 million – without having to cede one.

And the failure of those signings can’t go unnoticed here. The advantage of the Dodgers and Yankees isn’t just what they can buy when they’re spending. It’s what they can get rid of when they’re not. Consider this ridiculousness: In addition to Matt Kemp’s $21.5 million salary, the Dodgers will send $3.5 million to San Diego … to help the Padres pay for Kemp’s contract. Yes, the Dodgers are now paying for Kemp twice, which sounds like a metaphor come to life.

When dealing in this salary stratosphere, oddities almost seem normal. It’s what makes picturing Harper in a Dodgers uniform possible. Los Angeles has no long-term commitments to any outfield spot; the Yankees, with the Stanton deal clogging their outfield, aren’t nearly the ideal destination they once were. The Phillies and White Sox and all the other teams with minimal commitments wield financial might. The Dodgers and Yankees have that, recent success and the magnetism of history.

Slipping beneath the luxury tax is, in the end, merely a small piece of the financial puzzle for baseball’s behemoths. It’s also one that shows ownership the sort of creativity, resourcefulness and dedication that wins votes of confidence when seeking the opportunity to lavish hundreds of millions of dollars on one player.

For the rest of the baseball world, which peers toward the oceans with envy, this is a frustrating reality, one in which tens of millions of dollars get passed around in some shell game that ultimately behooves the team with so many advantages already due to its geography. That may not be fair, and that may not be right, but that’s real. And neither the Dodgers nor the Yankees – trying to meet head on in October, each aware how difficult that will be even as they endeavor to build the biggest, best team ever – will apologize for it, either.

More from Yahoo Sports:

• Dodgers agree to stunning 5-player trade with Braves

• Report: Ex-wife of slain NBA player arrested

• Yankees may have another big move in them

• ESPN releases texts, shows it’s focused on wrong thing