Documents, interviews show how agencies responded to rash of deadly overdoses in Austin

The rush of 911 calls from downtown Austin was the first clue about the wave of overdoses to come.

At least 10 EMS units were sent to an alley near a nightclub on East Seventh Street and began treating people for overdoses after 9:30 a.m. Monday, April 29. One man died in the alley and two were taken to the nearby Dell Seton Medical Center at the University of Texas.

Over the next 13 hours, authorities encountered at least three more deaths within a half-mile of one another in Southeast Austin and responded to dozens more overdoses.

Interviews with city officials and documents obtained by the American-Statesman provide the most detailed account to date of how agencies pooled resources and responded to the spate of overdoses, which authorities believe were caused by fentanyl — a synthetic opioid 50 times stronger than heroin that is often mixed into street drugs to increase potency.

By the time Austin-Travis County EMS declared the "overdose surge" over on Friday, May 3, 79 people had overdosed. Nine people had died, according to the Travis County medical examiner's office.

Though approved for medical use as a painkiller, synthetic opioids such as fentanyl cause more than 150 deaths per day, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Due to its high potency, when added to other drugs, it makes them more addictive as well as cheaper.

All nine people who died had fentanyl in their bodies, preliminary toxicology reports from the Travis County medical examiner's officer show, according to Hector Nieto, a spokesperson for Travis County. Cocaine was also present in eight cases and methamphetamine in three. Testing to determine the final causes of death could take up to 60 days.

In the days after the overdoses began, police seized crack cocaine, methamphetamine and marijuana that contained fentanyl, Austin police Lt. Patrick Eastlick said at a news conference.

Increased police presence and surveillance in areas of town most affected by the overdoses led to several arrests on drug-related charges and one firearm charge, according to arrest affidavits reviewed by the Statesman. But, as of Friday morning, Austin police said no arrests had been made or charges filed in direct connection to the overdoses, and the investigation remains ongoing.

The early hours of Austin’s mass overdoses

Kevin Lee, director of operations with the nonprofit Urban Alchemy, arrived at the Austin Resource Center for the Homeless around 4:30 a.m. that Monday in late April, he told the Statesman in an interview. The city of Austin pays Urban Alchemy to run some of its homeless shelters and provide other services.

When David Gray, the city’s homeless strategy officer, arrived at the ARCH later that morning and asked about possible overdoses in or around the shelter, Lee said he had no clue what Gray was talking about. They soon learned that just a block south, in the alley between Red River and Neches streets, someone had died of an overdose.

Addressing the situation quickly became a multiagency collaboration.

Lee and Gray began working with first responders and several service providers to flood the area with Narcan, a medication that if given in time can reverse opioid overdoses triggered by fentanyl, heroin and prescription drugs.

Lee said that in addition to providing food, water and Narcan and assisting EMS, Urban Alchemy staffers created flyers and distributed them in the area to educate people on the dangers of fentanyl and on how to use Narcan.

Security guards in at least in one case administered Narcan to someone in the alley before EMS arrived, a report obtained by the Statesman through the Texas Public Information Act says. The report did not specify who employed the security guards.

In addition to first responders, EMS sent members of its Community Health Paramedic Team, EMS Capt. Angela Carr said. The team offers health services to underserved parts of Travis County to reduce their reliance on calling 911.

Through the collaboration between the agencies and nonprofits such as Urban Alchemy and Caritas of Austin, which offers housing assistance and other services to prevent homelessness, “we saved lives,” Gray said. “In fact, I personally saw people receiving Narcan and other medical interventions and being able to recover” from the overdose.

Although the overdoses Monday morning occurred near the ARCH facility, Gray said no clients at any of the city-owned shelters overdosed in relation to the surge.

And those affected by the overdoses were not just people experiencing homelessness.

"There were patients that were unhoused; there were patients that were housed," EMS Assistant Chief Steve White said at a news conference April 30. "There were patients that were at their workplace, and there were patients that were out in public accessible spaces as well. It was not limited to one geographic location.”

Deaths in South Austin within a half-mile of one another

The suspected overdoses and deaths were not just isolated to downtown Austin.

Records obtained by the Statesman show three deaths occurring from Monday afternoon into Monday night in the East Oltorf area. The 911 calls were from the La Quinta Inn on East Oltorf Street, the Jack in the Box on East Oltorf and an apartment complex on Burleson Road, all of which are within a half-mile of one another.

One caller said the person who died had taken cocaine. Another said someone took a pill to go to sleep and wasn't moving.

Emergency medical services staffers responded to the most overdose calls Monday, Carr said, and then saw responses taper off throughout the rest of the week.

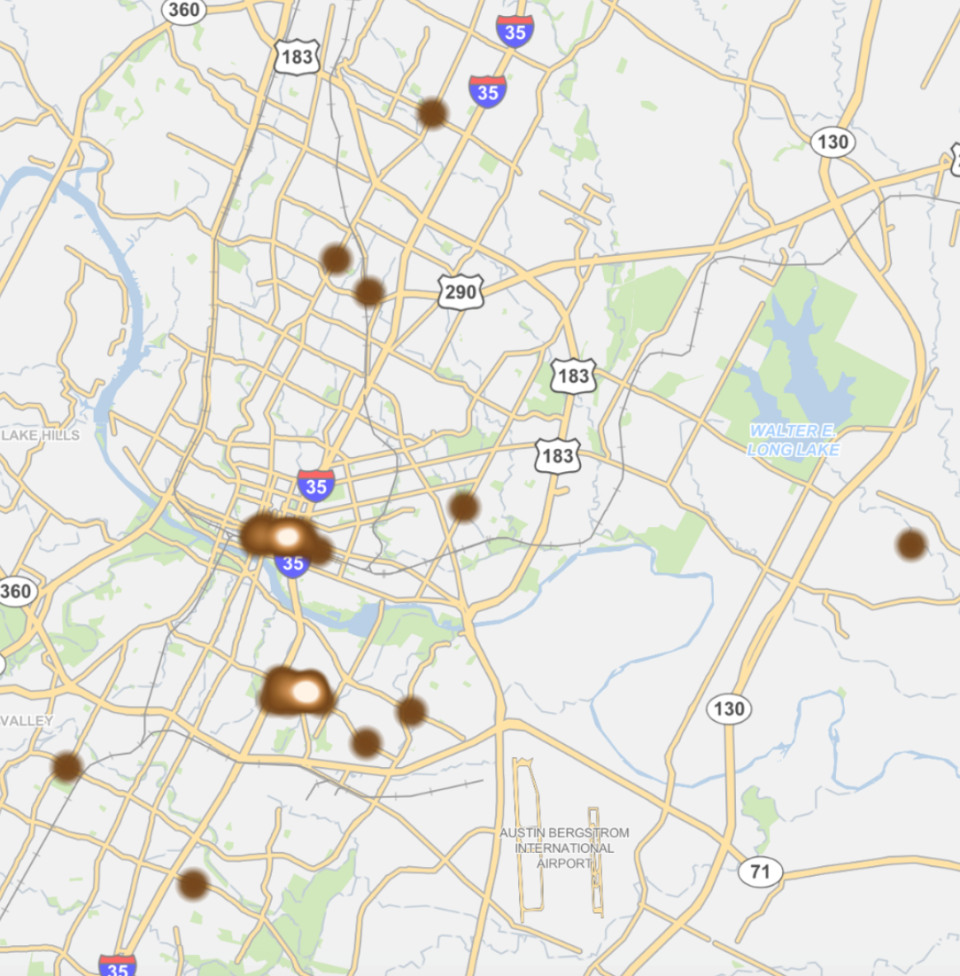

A map provided by EMS shows that while many of the 64 overdose calls to which EMS responded April 29 and 30 were concentrated downtown and in the East Oltorf area, calls were coming in across North, South and East Austin and Travis County.

Eight of the deaths occurred Monday and Tuesday of that week.

One death, which happened on the night of April 28, was not initially counted by the medical examiner's office due to the time frame but was later included in the total number of suspected overdose-related deaths, according to Nieto.

In half of the 79 overdoses in Austin that week, bystanders administered Narcan before EMS arrived. By the end of the outbreak, hundreds of doses of the drug — which commonly comes in the form of a nasal spray — had been distributed to the community.

“It's extremely important for us to have Narcan available on the streets and in the locations where it might be utilized,” Carr said. “It's instrumental in the survival rates."

This article originally appeared on Austin American-Statesman: How agencies responded to week of mass overdoses in Austin