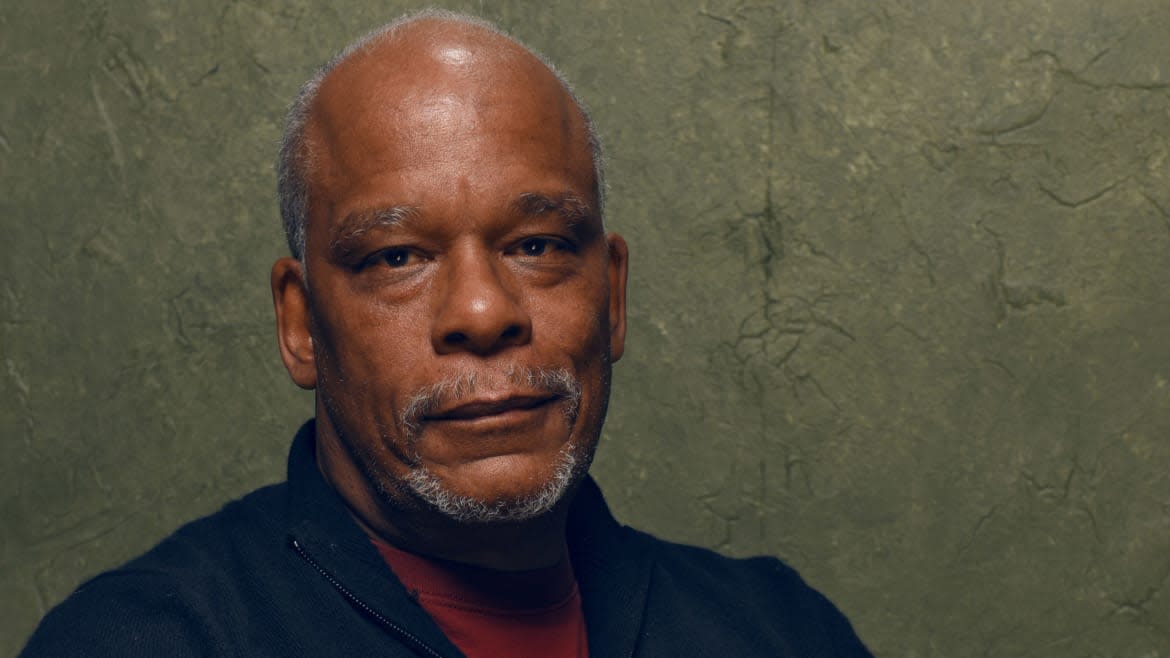

Documentary Legend Stanley Nelson Is ‘Very Proud’ of His Daughter’s Arrest at George Floyd Protests

Filmmaker Stanley Nelson has directed some of the essential documentaries about the history of black activism, freedom work, and culture in the United States, including: Marcus Garvey: Look For Me in the Whirlwind; The Murder of Emmett Till; a 2009 series about immigration across the U.S.-Mexico border; Freedom Riders; The Black Panthers: Vanguard of the Revolution; and most recently Vick for ESPN’s 30 for 30 series.

Naturally, as a result of his decades of work, he has a lot to say about the torrent of events currently taking place in the United States, from the coronavirus pandemic, to the killing of George Floyd by Minneapolis police, to the violent reign of President Donald Trump. And it’s the latter that Nelson believes undergirds the protests taking place in major cities and towns across the country.

According to Nelson, it’s essential to remember that not only has anti-black brutality by the state existed since the U.S. was formed, but Donald Trump and the current Republican Party have resurfaced a special kind of brutality and neglect at a national level. The director believes that Floyd’s killing—not even the most recent in a series of police killings of unarmed black Americans—has finally popped the lid off and stirred Americans, especially young ones, to more cohesive and collective action. I spoke to Nelson about his thoughts about the protests, the pandemic, and the future of policing in the United States.

Both within the space of this pandemic and protests against George Floyd’s murder, there’s been this kind of encouragement or drive toward productivity, particularly because many people are stuck inside or at home. There’s a focus on how you still get work done or still contribute to freedom work, for example. That’s made me think a lot about the question of how do you heal, how do you attend to yourself and to your community in the midst of active struggle? And I wondered, the Black Panthers documentary you made, a huge part of it was about how people couldn’t attend to their families and be in the Panthers. The structure was not built to support care work outside of active struggle, necessarily. I wonder if you think those reflections from former Panthers could be of use today?

Stanley Nelson: I mean, it’s strange because we can forget that the virus is still with us. How do you manage that? Everything else that’s going on at the same time? I have a 30-year-old daughter and two twins [a son and a daughter] in college who have come home because of the virus. And we had just moved up to Cape Cod when the pandemic broke out. So, my twins were up here, but when the protests started they wanted to come back to New York. They were going to hold one of those standards where “We're going [to the protests] and we’ll come back later because we want to be part of this.” And so we took them back to New York. So that was Sunday, and yesterday [June 1] they were out there marching, and they’re out there protesting today. And our oldest daughter Malana got arrested yesterday at a march in Atlanta, six hours in the criminal justice system. So that’s why I just wanted to take that call [ed note: Nelson briefly took another call near the beginning of our interview] because you know they took her phone—I didn’t recognize the number that just came up on my phone just now, and that’s what happened yesterday. They took their phones, so she called me from a phone that she could borrow.

Eric Garner’s Widow Feels Like She’s ‘Being Attacked by the Police’

George Clooney: America’s Greatest Pandemic Is Anti-Black Racism

And I’m glad that [my children] want to be part of [the protests]. You know, I remember a woman, Michelle, when we did Freedom Riders, and she came down one morning and she was 19 and one day she said to her mother, “I’m leaving cause I’m a Freedom Rider now,” and she left. And that’s what happened over and over again, with some of the Freedom Riders and the Black Panthers—young people don’t ask permission, they just join because they feel they have to. So I had to think about that, and in some ways I’m very proud of my children, but a little nervous too.

How’s your daughter Malana doing now?

She’s out. She got out last night, but [went back to the jail] to pick up her phone and her wallet, because they told her to come back for it, but last I heard they couldn’t find them. You know, it’s just a big mess. But she’s out, that’s the main thing. Phones, you can replace them.

Like all parents, most times, you’re dealing on, on two levels. On one hand you’re like, just stay home and be safe. But as a progressive person, I realize this is a very critical time and in some ways I’m proud of my children for getting out there. They have not been involved in the movement of marches or protests before this, really. It’s good to see that they’re involved. This has been an incident that has affected people in a way that no other has, and I think it’s important that [my children are able to] recognize that and realize they can be part of change and they have to be part of change. And so some of [my initial] reticence and doubt has gone because, it’s like you’re drowning, you’ve gotta reach for anything that will help save your life.

Why do you think George Floyd’s murder by police specifically has triggered such a widespread and direct involvement with young people across the country?

We’ve seen it over and over again. And so there’s no denying that that repeats itself over and over. We’ve seen videos over and over. We’re in the middle of a pandemic, so people have been cooped up for like 11 weeks or whatever it is. And I think that just the explicit nature of that video—this wasn’t a shaky camera [video], we saw the life drain out of this man. We saw it. And as many times as we might’ve seen people die in the movies, very rarely have we seen a video of someone dying over an eight-minute span of time. It’s an incredible video that has affected people, where this man is in some ways calmly pleading for his life. And there was no emotion from the police. It wasn’t like it was emotional; it was just, “We’re just going to kill you,” you know? Of all the things we’ve seen because of video cameras and phone cameras, it’s just an amazing piece of video.

The [white] woman in Central Park [Amy Cooper] who was gonna turn in a [black] birder [Chris Cooper, ed note: no relation]—she was essentially saying, “I will call my dogs on you if you don’t do what I want. I will call my dogs. I will call the police on you and you know who they’re gonna favor.” That reminded me of incidents that have happened in my life, where white people say, “I’ll call security. And we’ll settle this, because I’ll call security and you know what side they’re going to be on. You’re a black man and I’m white, and if they come, who knows what might happen.”

That dynamic has made me think a lot about the language around policing that has repeatedly come up in the midst of various activists and media personalities’ responses to Floyd’s murder. Some people are really focused on criminal justice reform, which always comes up with every instance of anti-black police brutality. But others are saying, “Actually we need to defund the police. We need to abolish policing. Or, at the very least, we need to abolish policing as we know it.” But a lot of people have a hard time imagining what it would mean if we didn’t have police. What are your thoughts about how we can imagine and formulate alternative strategies to policing that won’t bring harm to racialized bodies?

I don’t think police abolition is going to happen anytime soon—it happens in stages—but, we just finished up a project on the crack epidemic that will be on Netflix in a couple of months, and part of the trajectory charts the police going from the beat cop, to the war on drugs and the militarization of the police, and millions of dollars beginning to go into police departments. There’s this image early in the film when you see New York cops walking the streets, swinging their batons, and by the end of the film there are military vehicles with body armor and machine guns—crazy equipment. We can start out by thinking about defunding the police, demilitarizing the police. And then there’s also the idea of retraining the police so that they are not this occupying force with this kind of warrior mentality, because it creates this us-against-them mentality that we now exist in, in black communities and some other communities. There’s another way to be. It doesn’t have to be that way.

That brings up the various trainings that have been suggested for other kinds of public servants and workers in the public sphere. You directed the Story of Access training film for Starbucks after the infamous event where a black man had the cops called on him by an employee for simply being in the space while he was waiting to meet up with a business partner. The film you made constitutes a kind of anti-bias training and involves understanding personally what black people go through when they are policed and targeted in public and commercial space. And so I wonder about the education that police receive in relation to the education that workers receive before we go into vocations. Is there reason to think that police can unlearn the harmful ideas they are taught about community safety and “law and order?”

Yeah. There’s so much that can be done if we’re talking about retraining the police. We’re also talking about something that could be so much better for the actual police. I read something a police officer wrote about the feeling that they have of every time they step out of their car, they’re the enemy and the hate that’s generated when people see cops. I mean, could you imagine living through that, that being your life? There’s all kinds of studies about the trauma that police go through and then take back home to their families. So, police are already operating on this level [of instability]. So all it takes is [a police officer] who’s just a little bit off, you know, to take [an interaction with a civilian] to a higher level. So we gotta start with a low level of cooperation with people in the community so that the police are part of the community and not an occupying force.

But I’m thinking about how in your Black Panther documentary there are quite a few police officers, local police officers, who are unwilling to even admit on a basic level that there’s brutality in the force. There’s an FBI agent who ironically seems more willing to acknowledge the moral compromise of the COINTELPRO program, and that what they did was unethical and recklessly violent. Whereas it seems like a lot of the local police officers in the film—with the exception of a black former Chicago PD officer who commented on Black Panther Deputy Chair Fred Hampton's murder by police (though he was not present for it)—it seems like a lot of those policemen, white policemen for the most part, are very defensive about their choices, no matter the degree of violence. And that really took me aback in that they were given this opportunity to reflect on their experiences and their actions, and yet they were very defensive.

I wouldn’t say those police officers we interviewed for the documentary were defensive. I think, as you said, they just weren’t very reflective. You know what I mean? It’s not that there’s some part of them that believes what they did was wrong. I think police are not the most reflective group of people in the world. And in many ways they felt that they were following orders and what they did was the right thing to do. It’s funny because one of the cops who in the film says something about how, “We had to go out there and show the Panthers who were the dominant force,” that’s the same language that Donald Trump is using now.

Right. And for that reason there are a lot of people who are skeptical about police reform, because so much of this thinking is embedded within a structure of white supremacy. And the idea is that if you’re going to take a reform approach, you’re still going to end up with a police force that exists in a society that’s dominated by white supremacy. Do you really think we can reform the police through a series of programs or measures?

I’m not sure how far reform can really go. But we do have to make it so that they stop killing us. That’s the first step. And to understand that if you create violence that there’s a good shot that you will go to jail just like anybody else, that you can’t kill innocent people. That’s the start and who knows where it can possibly go. But in the future, somewhere where we have to have a whole different form of policing than we do now. Do you need somebody at this point, given human nature, to keep the peace? Yeah, probably, but I think we have to take it a few steps at a time. Did the civil rights movement [give] African-Americans equal [status] in this country? No, but it certainly was a beginning.

What we’re saying now is that you cannot kill us, and everybody has to look at the way that police do their jobs and the police have to look at the way they do their jobs, and think about the fact that there’s a better way. And if you’re gonna do it as a military force, and you’re going to confront people and hurt people and create actual violence, then there will be consequences. That’s the first step, and then we can go from there.

A scene from The Black Panthers: Vanguard of the Revolution

For you in your documentary film practice, is there anything in the events right now that has inspired your perspective going forward or how you might make films?

I’m inspired by seeing young people out there, and so many out there in the streets, because they feel they can make change and that’s really important. I’ve heard people say, “Well, what are young people doing?” Young people are letting people know that what’s happening is a problem. But there isn’t a movement there and young people often don’t know what it is they can do to solve these problems. And so in some ways, I think, young people were waiting and wanted to be part of a movement, which is a very hard thing to start. Not everybody can be leaders, but you can say, “OK, I’m going to get out there and lend my body to this march and lend my voice to change that.” So I think that you have a whole school of people, including my family who have been radicalized by this, who are thinking differently about their role in changing society.

Another thing I wanted to say was that if you talk about coronavirus and how over 100,000 people have died from it in the United States; if you talk about 40 million people who are now out of work; if you talk about how George Floyd was killed on camera by police; and all these other things that have happened, then you have to talk about Donald Trump. That’s a central piece to why people are out there marching. You have this government that we know—and so many people know it’s not just people of color, it’s young white people, too [working class people]—that this government doesn’t care about us. You know, we saw that kind of reaction to the coronavirus [from the Trump administration]. All the things happening here are also a protest against Donald Trump, and also against the whole Republican Party, who haven’t said a word about what’s going on. And this man, Donald Trump, talks about how he’s going to dominate, how he’s going to call out the Army, and nobody in his party said a word.

PBS has re-released The Black Panthers: Vanguard of the Revolution for streaming on their platform as part of a slate of new and existing programming about race in America.

Get our top stories in your inbox every day. Sign up now!

Daily Beast Membership: Beast Inside goes deeper on the stories that matter to you. Learn more.