Doctors find virus in a pond, use it to destroy antibiotic-resistant bacteria in man's heart

After Yale doctors replaced a major blood vessel in a 76-year-old man's heart, his chest became infected with bacteria.

The usual solution would be to destroy the harmful bacteria with antibiotics. But the doctors found their antibiotics wouldn't kill the microbe, P. aeruginosa, which like many bacteria in recent years, had become resistant to traditional drugs.

So, doctors turned to an experimental solution, involving a bacteria-killing virus known as a bacteriophage.

SEE ALSO: This Apple Watch wristband successfully detected abnormal heart rhythms

Running out of options, doctors employed this still-experimental treatment, inserting hundreds of thousands of viruses — known to combat this very bacteria — into the man's chest. On Thursday, Yale announced the treatment worked and published the study in the journal Evolution, Medicine, and Public Health.

Bacteriophages, commonly referred to as phages, have been known for over a century. But after the discovery of penicillin and the popularization of the conventional antibiotics we use today, phages fell out of favor for battling deadly bacterial infections.

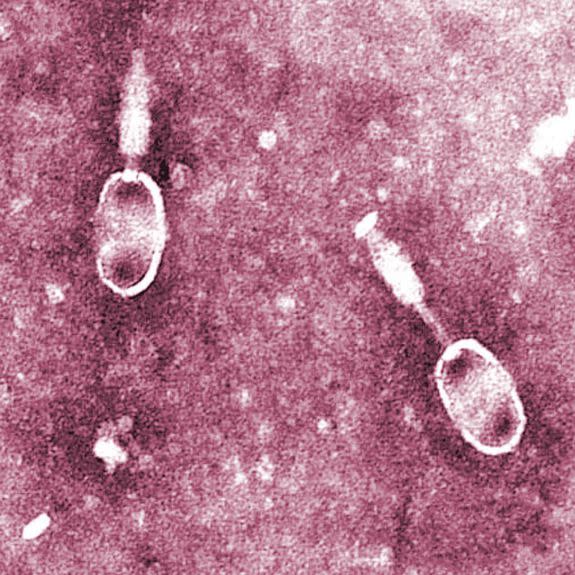

Image: microbiologybytes

Yet as bacteria grow increasingly resistant to conventional drugs, phages — strange looking viral structures that can have leg-like attachments used to land on bacteria — have stepped back into the picture.

"Antibiotic resistance is becoming a more serious problem now, so phages are a good alternative," said Ben Chan, the research scientist at Yale's Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology who proposed using phages to attack the bacteria in the patient's heart.

Two widely-recognized sources of antibiotic resistance, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), are the overprescribing of antibiotics and the use of antibiotics in our food supply — like pigs and cows. Both give bacteria and germs more exposure to our drugs, and more opportunities to adapt immunities to them.

The phages employed in this treatment were collected from Dodge Pond in Niantic, Connecticut, although Chan has phage samples from all over the world. Different research teams pan in water bodies for the microbes in disparate locations and send Chan what they collect.

"You never know what you’re gonna get, really," Chan said.

Image: courtesy of David Post/Yale University

After exposing the Dodge Pond phages to the common P. aeruginosa in his Yale lab, Chan found a match.

The FDA has yet to approve clinical studies for the phage treatments, so after the patient (who happened to be a doctor) agreed to participate in the treatment, Yale got permission from the Food and Drug Administration to put the viruses into the man's heart and chest.

"Studies like this highlight the potential for phages," said Timothy Lu, an associate professor of biological engineering at MIT who was not involved in the treatment nor the study, in an interview. "More studies need to be done, but anecdotes like this are really powerful."

Phages may prove to be an important solution to increasing antibacterial resistance: In November 2016, a bacterial "superbug" proved resistant to 26 different antibiotics, and killed a woman in Nevada.

Image: WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

But a major limitation is that phages cater specifically to certain bacteria, whereas conventional antibiotics can be used to combat a wide swathe of bacterial infections.

"Most antibiotics are pretty broad spectrum in nature," explained Lu. "As a result, doctors are used to dispensing antibiotics without knowing which bacteria are present."

"But phages are different," he said."It's really important to have a high confidence of the bacteria that is causing the disease."

This means finding ways to more rapidly diagnose the bacteria in question, as bacterial infections often need to be fought promptly.

Scientists and regulators have a long, tedious road of experimentation ahead of them before these viruses can be regularly deployed against infections — and not just in experimental treatments like the one at Yale.

But as the medical community becomes mobilized to fight the growing threat of antibiotic resistance, doctors are becoming increasingly curious about finding phages to kill bacteria. So they call Yale's Chan, who has a library of the bacteria-annihilating microbes.

"I get calls, emails, and texts pretty frequently," he said.

WATCH: Google is learning how to predict heart disease by looking at your eyes