Doctors discover why stressed out people have more heart attacks

Emotional stress has long been considered a major risk factor for heart disease. But doctors have struggled to determine exactly how all that tension and mental strain can harm your heart.

A new study suggests that the brain's fear and stress region — the amygdala — might be the connecting piece.

Researchers found that heightened activity in the amygdala is associated with a greater risk of heart disease and stroke. The new research was published this week in The Lancet.

SEE ALSO: How your uncle's conspiracy theories trigger your brain's anxiety areas

While larger studies and additional research are needed to confirm the findings, the researchers said their study could eventually lead to new ways for treating stress-related heart risk.

"Our results provide a unique insight into how stress may lead to cardiovascular disease," Dr. Ahmed Tawakol, a cardiologist at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, said in a statement.

Image: Stephen Maturen/Getty Images for Fitbit

"This raises the possibility that reducing stress could produce benefits that extend beyond an improved sense of psychological well-being," he said.

"Eventually, chronic stress could be treated as an important risk factor for cardiovascular disease."

Smoking, high blood pressure and diabetes are other well-known risk factors for heart disease — a condition that kills about one in four women in the United States.

People often develop chronic stress if they live in poverty, have heavy workloads or are worried about losing their jobs. Higher stress levels can in turn lead to depression and other chronic psychological disorders, Ilze Bot, a senior biopharmaceutical researcher in the Netherlands, wrote in a commentary that accompanied The Lancet study.

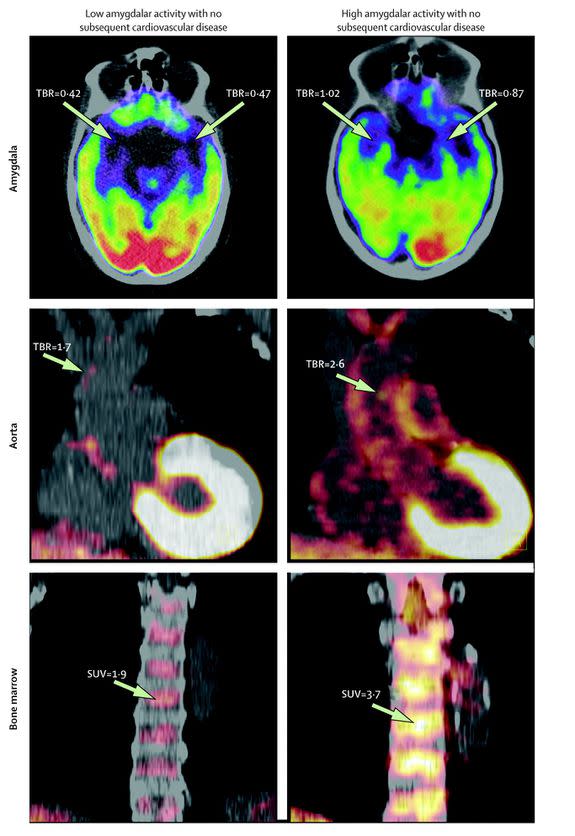

For the research, nearly 300 participants underwent a combined PET-CT scan to record their brain, bone marrow and spleen activity, as well as inflammation of their arteries. Researchers tracked the patients for an average of 3.7 years to see if they developed heart disease.

Image: Tawakol et al, 2017, The Lancet

Over this period, 22 people, or about 7.5 percent of the group, suffered cardiovascular events such as heart attack, angina, heart failure, stroke and peripheral arterial disease.

Patients with more activity in the amygdala region had a greater risk of later developing heart disease, and they developed those problems sooner than participants with lower amygdala activity, according to the study.

Bot, who was not involved in the study, said that while more research is needed, the results do establish a connection between stress and heart disease and identify chronic stress as a "true risk factor" for acute heart problems.

"Given the increasing number of individuals with chronic stress, [the data could] be included in risk assessments of cardiovascular disease in daily clinical practice," she said.