Should we ditch the names of Hitler beetles, Mussolini butterflies?

It is just 5 millimetres long and tends to live hidden in caves and although many experts have never seen this beetle, it is causing quite a stir.

Its scientific name is Anophthalmus hitleri. The brown, eyeless beetle was named after Nazi dictator Adolf Hitler - and is very popular with certain collectors because of its name.

There are several examples of animals with controversial designations.

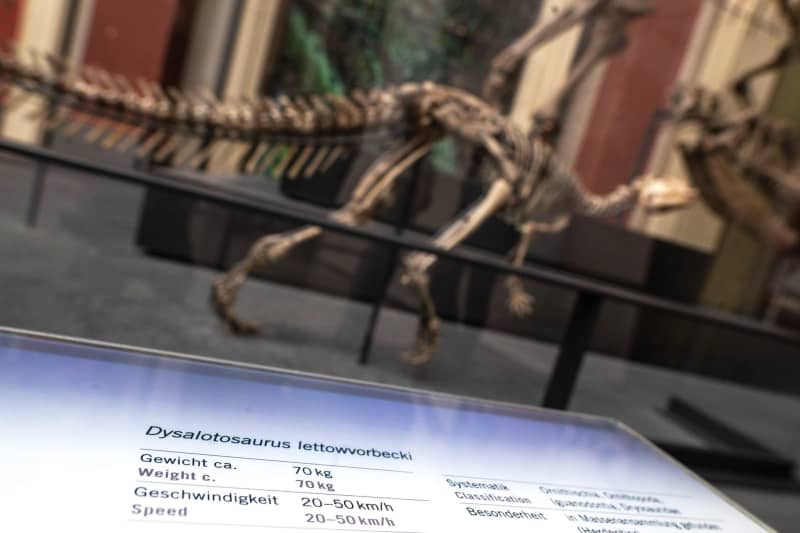

Another bone of contention is on display at Berlin's Museum für Naturkunde (Natural History Museum) - the dinosaur Dysalotosaurus lettowvorbecki, named after Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck, who was involved in atrocities in Africa as commander of the German colonial army.

Most animals were given their scientific names a long time ago but are they still acceptable today?

As streets are renamed, monuments removed, and language scrutinized - should we reconsider these designations too?

Controversial animal names are a hot topic discussed within the scientific community but nothing is likely to change any time soon.

How new animal species get their scientific names

Every year, thousands of new animal species are designated worldwide. The international rules for zoological nomenclature define how taxonomists should proceed.

According to Berlin-based zoologist Michael Ohl, the nomenclature does not specify the content. Researchers are free to choose the names as long as they are technically correct.

"These apply as soon as they are published and can then no longer be deleted," Ohl explains.

There is a long tradition of naming newly discovered animal species after people - to flatter a generous donor, to honour family or friends or to attract attention with the help of prominent namesakes, as Ohl writes in his book "The Art of Naming."

Pop star Taylor Swift has inspired the naming of a millipede species, beetles have been named after actor Leonardo DiCaprio and climate protection activist Greta Thunberg. One moth is now called "Neopalpa donaldtrumpi" due to the striking golden flakes covering its head, which scientists found resemble the former US president's striking hairstyle.

Ethical concerns with naming practices

Naming animals after people can pose problems, as seen with examples like the Hitler Beetle and a butterfly honouring Italian dictator Benito Mussolini.

But it's not just historical figures, even contemporary individuals can complicate matters. What if a politician takes a turn towards extremism or a film star faces allegations of misconduct?

Some scientists argue that species names can also carry discriminatory or racist connotations.

A group of experts scrutinized the names of over 1,500 known dinosaurs. While the scientists are tight-lipped about the study's findings until publication, reports from the scientific journal Nature suggest troubling discoveries.

Among them, fossils unearthed in Tanzania between 1908 and 1920 often bear names of German researchers rather than local expedition members, or they derive from colonial place names. Additionally, a majority of gender-specific names tilt towards males.

Is this really a big deal?

According to an estimate by the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN) - the body that publishes the naming rules - around 20% of animal names are eponymous.

These are names that are intended to honour individuals. These are therefore the largest group of names that could offend, the commission writes in a statement.

Toponyms, or location names, could also be perceived as offensive. They account for around 10% of names.

Several hundred thousand accepted scientific names could therefore be called into question, it says. In the case of dinosaur names, the researchers rated less than 3% as problematic.

In terms of numbers, the problem is insignificant, explains Evangelos Vlachos from the Museum of Paleontology Egidio Feruglio in Argentina, in the Nature report.

Nevertheless, the issue is of great relevance. It is necessary to critically review previous practice and try to correct mistakes, he says.

What the scientific community thinks

The ICZN refuses the renaming of animals based on ethical concerns. "Of course, we recognize that some names can cause discomfort or offence," says Daniel Whitmore, a taxonomist who is a member of the commission.

"It's not our job to judge whether names are offensive or ethically unacceptable, because that's a very subjective and personal matter," he adds.

The focus is on maintaining a universal and clear classification system, he says.

While zoologist Ohl agrees that renaming species poses challenges, he emphasizes the need for the ICZN to address ethical issues, even though it would be like opening "Pandora's box," he says.

Exploring solutions

Renaming controversial species, like the Hitler Beetle, may not fundamentally alter perceptions.

"In a case like the Hitler beetle, renaming it wouldn't change much at all," says Ohl. Anyone who wants to collect the Hitler beetle because of its name will continue to do so, he adds.

One way of taking a critical look at controversial animal names would be to contextualize their history in museums, to encourage reflection.

The Berlin Natural History Museum has already done this with Dysalotosaurus lettowvorbecki.

A display board reads: "Unfortunately, the strict rules of taxonomy preclude any subsequent changes to species names once they have been assigned."