A different epidemic: 100 years ago, a virus raged through Nevada, and it wasn't Spanish Flu

A bawling bovine, mad with a virus sweeping the West, stood between Sarah Olds’ children and the house.

For two hours the children had been stranded on a haystack on the family's Nevada ranch, unable to get home as the rabid cow pawed and raged outside the house. It was starting to get cold, and the children pleaded with their mother to let them sprint for the house as the sun dipped low in the sky.

"No, sir!" she yelled at the kids from the front porch. "Burrow down under the hay to keep warm, but don't dare come home."

Olds awaited her eldest son, hopeful that he'd come home soon from a day of hunting, and with enough ammunition to shoot the crazed cow dead.

It was 1916 and there was a virus spreading in Northern Nevada.

'Greatest calamity' to hit the state

While many scholars have drawn parallels between today's COVID-19 pandemic and the nationwide Spanish Flu epidemic of 1918, Nevada fought another virus 100 years ago, one very different from today's novel coronavirus.

In many ways, however, the battle was the same, marked by public pushback against mitigation measures and the difficulty of balancing the protection of livelihoods with the fight against an infectious disease.

From about 1915 to 1920, the state was grappling with an outbreak of rabies that threatened not only the health of people and animals, but also the state's culture and economy.

It was considered the "greatest calamity that had ever occurred in the state," according to the 1984 article "Rabies in Rangeland Environments," published by the scholarly Rangelands Journal.

Ranchers' livelihoods were particularly at stake as their livestock were bait for wild animals that roamed the desert in search of something, anything to bite.

Like the resistance seen toward measures to prevent the spread of the novel coronavirus, there were Nevadans then who also were reluctant to change their practices to prevent the spread of rabies. Ranchers most of all feared changes could irreversibly affect their viability as a ranch. One misstep could end an entire operation.

Animal activists and wealthy elite alike also balked at top-down orders, the most controversial one at the time being to quarantine and muzzle all dogs.

In her own home, Olds, the pioneering cattlewoman, bickered with her family about whether rabies was worth worrying about. The bickering stopped when Babe the cow went mad.

"She bellowed ... the most maniacal bellow I've ever heard. She dug holes two feet deep in the ground with her hooves and horns. She chased birds, chickens, anything that moved, and her whole body twitched and writhed all the time,” she wrote in her book, "Twenty Miles from a Match: Homesteading in Western Nevada."

That morning, her son had teased her when she told him to save a bullet for Babe. The family told Olds it was just her imagination.

By day's end, no one was laughing. As her eldest son returned home from the hunt, the deranged cow charged at him. With one shot to the head, the cow was dead.

"If I had known he had only one shell, I think I would have collapsed," Olds wrote.

Worldwide, rabies is estimated to cause 59,000 human deaths annually in over 150 countries, with 95% of cases occurring in Africa and Asia, according to the World Health Organization.

It is a gruesome and often lethal virus if untreated. The bullet-shaped virus infects the central nervous system of mammals, ultimately causing disease in the brain and death if untreated with a vaccination developed in the late 1800s by Louis Pasteur, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Today, rural populations around the world are most vulnerable. It was no different in the early 1900s in the Silver State. Homesteaders were settling among their feral neighbors, which gave the rabies epidemic further ability to devastate the human population of the West. The virus, which can infect any mammal, often leads to aggressive biting behavior in the host animal to maximize chances of infecting a new host, according to the CDC.

Cases were reported as early as 1909 in the Southwest, according to newspaper articles at the time, but they were spreading rapidly by 1915 throughout California and Nevada.

Scholars suggest the outbreak may have originated with animals such as coyotes in the Southwest, which in turn attacked and spread the virus to livestock and pets.

In his book, "Time of the Rabies," Nevada author Robert Laxalt painted a picture of the time through the eyes of a fictional Carson Valley sheep rancher, his cowboys and his family.

In the book, a rabid coyote attacks a sheep, a prize bull, a horse and a border collie. Rancher Pete Lorda realizes what's at stake and how quickly he'll have to impress upon his young ranch hands the importance of taking the matter seriously.

"Anything that acts crazy, shoot it." He hesitated, as if realizing the weight of what he was going to say. "Even your dogs."...

The gathering disbanded in silence. Unmoving, his shoulders stooped, Pete Lorda said to the veterinarian, "How bad will it get?"

"Pete," said the veterinarian with feeling. "I can't tell you because I haven't come up against anything like this before. It could spread like wildfire. We're talking epidemic."

The matter of muzzles

For centuries, dogs have been one of the greatest rabies threats to people because they are often the link between humans and the rest of the animal world.

When the outbreak began to take hold, state and local governments in the western U.S. began turning to muzzles as a preventative measure on the advice of health experts.

In 1915, immediately after Nevada started seeing rabies cases, W.B Mack, a veterinarian, bacteriologist and director of state veterinary control service at the University of Nevada in Reno, started publishing desperate public service announcements in newspapers around the state.

"In a community where rabies is prevalent, the real dog lovers should seek to protect their dogs against infection, and it seems to me that a muzzling ordinance ... should meet with the approval of all owners and lovers of dogs," Mack wrote.

He added that this was most imperative in rural areas since rabid animals, and their trail of victims, were more likely to go undetected.

Dogs at the time served as protection for both humans and livestock, as herders and companions in lonesome stretches of high desert.

So in a fight that's reminiscent of today's pushback against mask-wearing, many rebelled when experts focused on muzzling their furry friends.

Within a year, however, the situation had become acute, according to Mack.

"The infection has spread over the northern counties until practically half the state is involved. It is the most serious epidemic with which Nevada has ever had to deal, both in its bearing upon human health and the livestock industry," Mack wrote in 1916.

That year, the Elko Independent reported a $100,000 loss in livestock statewide, which would equate to about $2.5 million today.

And it began taking a human toll. More than 40 people were treated for the disease, the same article reported, most at the university in Reno.

The first human death reported in the state was a 1-year-old Humboldt County boy who'd been drinking milk from the family cow, which died from rabies days before the child took sick, the Elko Independent reported in February 1916.

How they stopped the spread

Leaders in the West in 1916 organized a rabies convention to share ideas and policies, and the Silver State ended up creating a state rabies commission to dictate decisions made at home.

Most counties enforced muzzling requirements, with some counties enabling law enforcement to shoot and kill any dog seen off leash. If leashed but not muzzled, the penalty was a $100 fine, equal to $2,500 today.

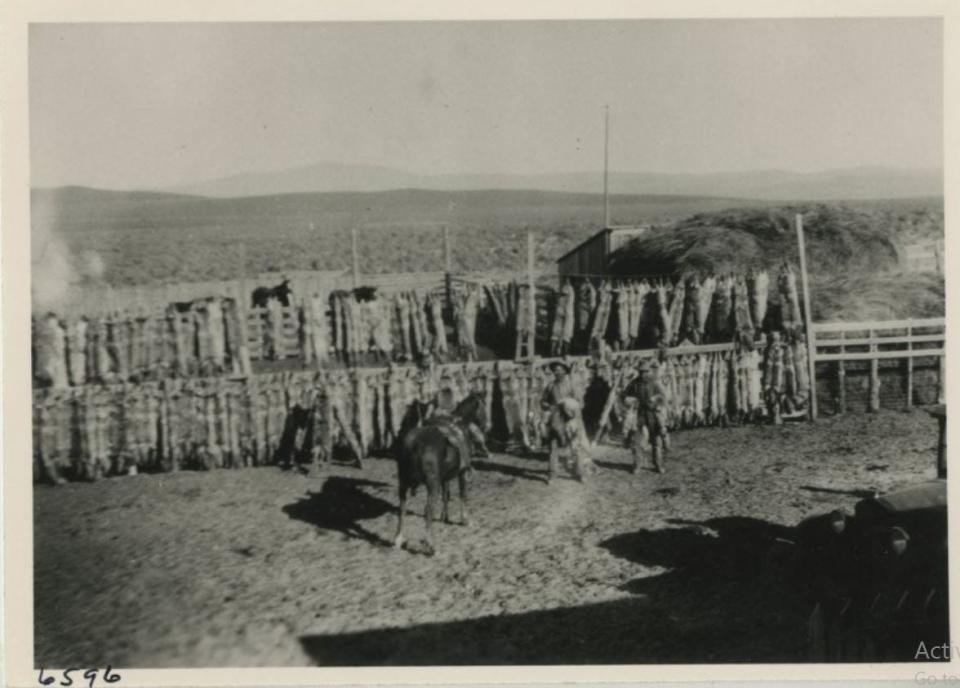

Ranchers also searched for solutions to one of the greatest challenges faced by their herds: Protecting their animals from rabid coyotes while moving them south during the winter. Staying in place meant running out of food. Moving them to greener pastures meant running a gantlet of rabid animals.

In his novella, Laxalt described one fictional scene of the kind of coyote attack likely experienced by ranchers at the time:

The clearing where the band had been was a scene of utter chaos and crashing gunfire. The line of coyotes had reached the band and were darting everywhere, snarling and slashing as they went...Then suddenly, the deafening gunfire came to a stop, and all that could be heard was the bleating of ewes and the plaintive crying of the lambs that had been bitten. His head bowed and his feet dragging, Lorda was weaving through the clearing, counting the dead and wounded.

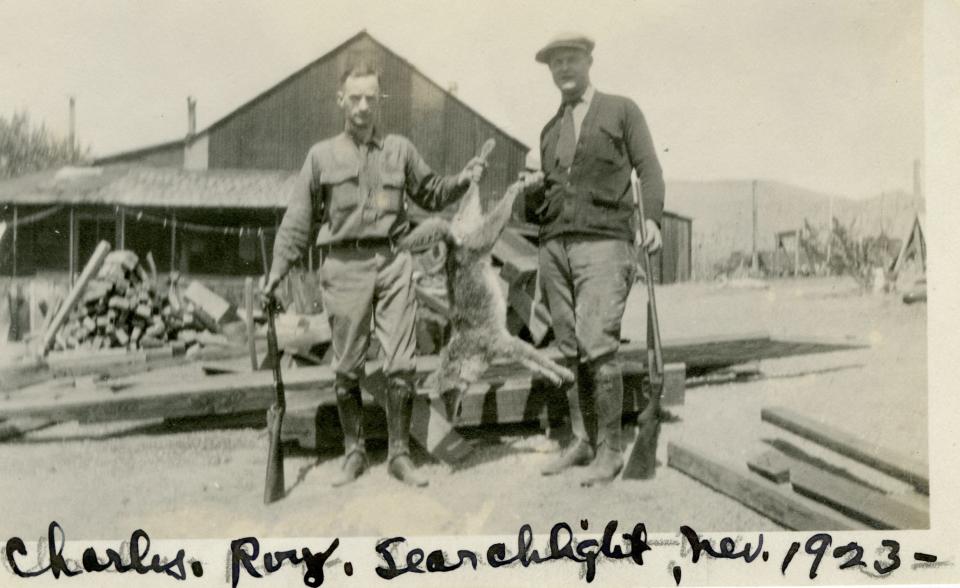

As a result, bounties for coyote carcasses increased as incentive to kill as many coyotes as possible. Wipe out the coyote, wipe out the disease, officials figured.

The population was culled dramatically from Idaho to California. In Oregon, hunters could snag as much as $17.50 per head for a coyote.

It's difficult to find any conclusive death toll or total cost from the rabies epidemic of the early 1900s in Nevada. Unlike today's coronavirus pandemic, the number of people who died appears to have remained relatively low, thanks to muzzling ordinances and Pasteur's immunization treatment.

While some skeptics of the vaccine existed, most were eventually more fearful of the almost guaranteed death if a rabies wound was left untreated.

The cost for the state's agricultural industry, however, was hundreds if not thousands of livestock and animals.

In Olds' case, she ended up losing five head of cattle during the outbreak, including a prize red Durham bull that the family had spent a full year's savings on.

"To me, the bull represented the coming realization of my dreams," wrote Olds.

Lessons learned

The COVID-19 pandemic has been vastly different from the rabies epidemic a century ago. For one thing, the greatest toll has been on human lives: more than 3,300 Nevadans lost last year. Countless businesses have closed, and many families have found themselves in need of assistance.

Few know the human impact better than Caleb Cage, the state's COVID-19 response director. He's a former head of the State Division of Emergency Management and Homeland Security and an Iraq War veteran.

"In my five years of crisis management, and nearly two decades of leadership, this pandemic is by far the most challenging and complex set of problems that I have ever encountered," said Cage.

Cage, like many Nevadans, had never heard of the rabies epidemic that plagued his home state a century ago. But he was familiar with the Spanish flu.

In his job as emergency manager, he was tasked with keeping the state prepared for responding to a similar flu epidemic. That preparedness included regular drills for distributing a vaccine to the public.

The challenge with any epidemic is there will always be competing interests, Cage said. Preventative measures will often upend the lives of people, whether it's their level of comfort, or their financial security, or their typical freedoms.

"There hasn’t been an easy day, or an easy decision, or an easy policy to recommend," said Cage. "All of the decisions have been hard. They have all come down to a balance. If we go far too this way, we may lose lives, and if we go too far the other, we also may lose lives for other reasons."

While memories of the century-old rabies outbreak have all but faded, many hope lessons learned from the coronavirus pandemic will stick.

Olds, who went on to run a successful ranch resort, perhaps said it best.

"As time is a wonderful healer, so is it a good 'forgetter,'" she wrote.

This article originally appeared on Reno Gazette Journal: A different epidemic: How rabies ravaged Nevada 100 years ago