They died in the storm. Why weren’t they counted?

Officials in North Carolina, South Carolina and Virginia counted 59 lives lost due to Hurricane Florence’s slow churn in September 2018.

In North Carolina, which bore the brunt of the storm, the count of the dead continued into the painful months of recovery that followed.

Deaths began the day before Florence made landfall and ended in January, according to the list compiled by emergency managers and health officials.

But a review of death records, obituaries and fundraising appeals by The News & Observer found that officials likely understated the death count.

Among the uncounted:

▪ Isnanik Tua, 44, a sushi business owner who suffered an aneurysm after evacuating from Wilmington with her husband and two children.

▪ Forest “Wayne” Crigler, 85, a retired electrical engineering professor who fell into a coma on a 13-hour car ride from the coast.

▪ Paul Leroy Lucas Jr., 65, a retired high school teacher who died in his sleep at a Wilmington shelter.

▪ Kari “Mandi” Mintz, 39, a mother of two who overdosed at a shelter in Shallotte.

All four got sick or or had their symptoms worsen while fleeing the coast or hunkering down in a shelter. Officials declined to explain why they were left off the official list despite federal guidelines that advise counting deaths linked to evacuation.

Why is this important? A full accounting, people working in public safety, emergency management and public health say, helps them identify ways to keep people safer during disasters and recovery, providing insights that can save lives.

The omissions from the Florence list spotlight the stress of dislocation.

Tua’s Facebook page, for example, shows she had been closely monitoring the storm.

Two days before Florence made landfall, she posted a photo of a rainbow arching above the roof of Lowes Foods in Wilmington. “Rainbow before the storm,” she wrote, urging her friends to be safe. She later posted a news article with the headline “8 A.M. Update: Florence to be worse than thought.”

The Indonesia native fell ill at a Goldsboro gas station and died days later at a hospital.

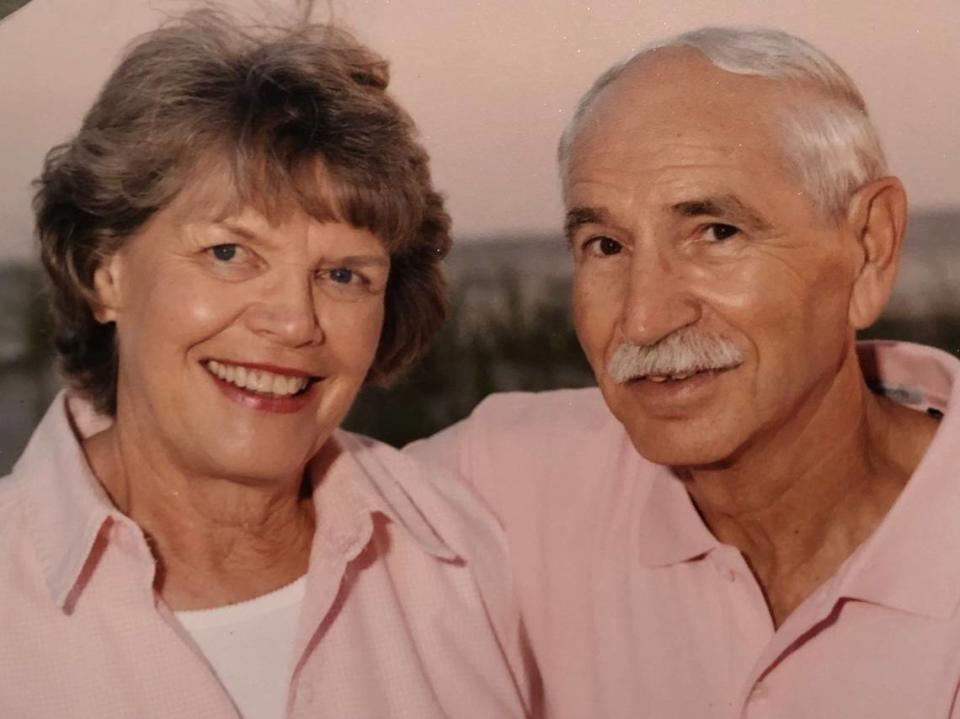

Crigler, an avid athlete into his 80s, was staying at a rehabilitation center in Morehead City and dealing with symptoms of Parkinson’s disease as Florence whirled off the coast. His wife, Elaine, picked him up after the facility decided to send its patients inland.

The couple, who had retired to Emerald Isle, planned to stay with a daughter in Pinnacle, near Pilot Mountain, but the father of four fell unconscious along the way and never woke up.

Lucas and his wife, Irene, left their home in Castle Hayne to stay in a hotel that, lacking a generator, soon became sweltering. They returned home the day after landfall, but left again when a tree fell and the house began to flood.

Lucas was blind and used a wheelchair as a consequence of diabetes. His wife helped him into the car in the middle of the night, wading through stormwater. They followed a caravan of neighbors to E. A. Laney High School, where both Lucases had long served as teachers.

The couple then rode in a bus to a shelter for people with special medical needs. Lucas needed dialysis, his wife said. He began to have heart problems and died during the night. Irene Lucas was hospitalized soon after. An infection from the stormwater led to amputation of part of her foot.

Mintz checked into a shelter at Brunswick High School about a week after detoxing from heroin in a hospital, according to her mother, Patsy Hewett. The doctors diagnosed her with Parkinson’s disease, which piled on top of other health problems: COPD, pancreatitis, Hepatitis C and depression.

As they prepared to go the shelter, Hewett said, Mintz was not acting like herself. Her addiction treatment was on hold because the grant that paid for it ended. The air conditioning was broken, and “water was pouring down her legs.” She kept repeating, “I got to get us ready to go.”

Mintz overdosed on fentanyl, a strong synthetic opioid, and gabapentin, a medication used to treat epilepsy and nerve pain, autopsy records show. Both drugs are commonly abused.

A spokeswoman from the Brunswick County Sheriff’s Office said naloxone, an opioid antidote, was available at the shelter. It was supposed to be, based on lessons learned from Hurricane Matthew two years before. Hewett did not recall the antidote being used.

A new approach to counting storm deaths

The way the toll of hurricanes like Florence is tallied has been changing amid predictions that climate change will bring more frequent, slower-moving and more drenching tropical storms.

Scientists have recently focused on the usefulness of looking at deaths due not just to a hurricane’s wind and rain, but also to the conditions a storm leaves behind.

A 2017 study of peer-reviewed articles and other documents found “no consistent approach for attributing deaths to a disaster.”

The same year, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention put out new guidance on how to document disaster fatalities in an effort to change that.

Recording a death as disaster-related on the death certificate is crucial for ensuring a full accounting of the storm, the CDC said.

Under the new system, deaths indirectly tied to a hurricane should be counted. That means natural deaths — from exacerbation of a chronic disease or cardiac arrest, for example — should be included if the disaster contributed.

The CDC instructs medical examiners to consider two key questions when weighing whether a death could be indirectly related to a disaster:

▪ Did unsafe or unhealthy conditions from the disaster contribute to the death?

▪ Did the forces of the disaster lead to temporary or permanent displacement, property damage, or other personal loss or stress that contributed to the death?

If so, the death should be included in the official count.

Resistance to transparency

It’s unclear exactly how diligently officials in North Carolina, South Carolina and Virginia are pursuing a complete picture of the storm’s devastation or how they expect to derive lessons from all of the lives lost.

Health officials in each state declined or did not respond to interview requests, but some information was provided by email.

Medical examiners in North Carolina voluntarily adopted “aspects” of the CDC’s guidance, a spokeswoman for the N.C. Department of Health and Human Services said in a statement.

The guidelines were used in determining whether a death was disaster-related for cases that came under the jurisdiction of the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, Kelly Haight Connor said in an email, but North Carolina did not adopt the CDC’s recommendations on how to complete death certificates.

The main office “piloted” the guidelines during Florence and shared information with local medical examiners in advance of the next hurricane, Michael, Haight Connor wrote.

She did not comment on the uncounted cases identified by The News & Observer, but said that not all evacuation-related deaths should count. Every possible hurricane-related death reviewed by a local medical examiner is also reviewed by a forensic pathologist in the main office, Haight Connor wrote.

South Carolina’s Department of Health and Environmental Control said in a statement that it did not communicate instructions to those responsible for certifying deaths at the county level prior to Hurricane Florence.

“While there have been no changes to DHEC’s regulatory guidelines following the release of the CDC guidance, or after those weather events, we have contacted certain coroners to ensure that the cause of death, if directly or as a result of a disaster event, is definitively labeled as such,” the statement said. A spokesman said those calls to coroners were prompted by reporters’ questions.

Officials in Virginia declined to provide any person-by-person accounting. The state Department of Health gave input to the CDC on disaster-related deaths but chose not to use the templates the CDC provides, Rosie Hobron, statewide forensic epidemiologist, said in an email.

“One of the biggest issues is that the forms are very lengthy and ask many questions that are not elements we collect during our death investigations,” she said. “Additionally, we have an in-house epidemiologist that collects, reports, and maintains records of all our deaths attributed to surveilled events.” Surveillance for Florence is ongoing, she said.

None of the states appear to have done a statistical analysis of death records to provide a check on the official disaster count.

Researchers from The George Washington University who evaluated “excess mortality” after Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico found that deaths following the storm were high above expected levels months after the storm hit.

They recommended their model be used following other disasters, in part because they found many physicians were unfamiliar with death certification standards.

“This approach could become a standard methodology for post-disaster mortality data analysis and public health performance assessment,” they wrote.

Why a detailed death count matters

Data on lives lost informs public health research, prevention strategies and emergency preparation.

“We want to stop disaster deaths,” said Ilan Kelman, who teaches at the Institute for Risk and Disaster Reduction at University College London. “To do that, we need to understand who is dying, why they are dying and what intervention we could do in order to stop them from getting into situations in which they end up dying.”

History is full of examples of public safety improvements born of tragedy.

Based on the fatality and damage reports after Hurricane Andrew, for example, Florida revamped its building codes.

Florida added generator requirements for nursing homes after 14 patients died in sweltering care facilities in the wake of Hurricane Irma.

And the observation that roughly half of the deaths directly attributed to tropical cyclones over the past 50 years were due to the abnormal rise of seawater during a storm — called a “storm surge” — led the National Weather Service to develop a better warning system, launched in 2017.

“Prior to that, we certainly had hurricane watches and warnings,” said Ed Rappaport, the deputy director of the National Hurricane Center, who reported the finding in a 2014 paper, “but those were based primarily on the wind speed. And while wind is important, as we mentioned, it’s not the deadliest of forces — storm surge is — yet we didn’t have an explicit warning for storm surge.”

The hazards require different responses, Rappaport said, in part because they can occur in different areas and at different times.

“For wind, except in perhaps the most extreme storms, one can find safety typically in a well-fortified structure near to home,” he said. “But for storm surge, the appropriate response is almost always evacuation.”

Lessons from the official fatality list

For this article, reporters reviewed the official list of casualties and gathered information from law enforcement, health officials and victims’ family members as part of an effort to identify possible upgrades in disaster preparation and response.

In addition to identifying omissions, the investigation pointed to several ideas for improvement.

Among the findings:

▪ Vehicle-related deaths constitute 44% of the total, which suggests measures to keep people from driving while roadways are inundated and trees are down should be re-examined.

Kelman, of the Institute for Risk and Disaster Reduction, said the “Turn Around Don’t Drown” campaign deserves more attention from researchers. Renewed study could answer two important questions and improve policy, he said: Why do people choose to drive on flooded roads? And perhaps more importantly, what were their options?

▪ About two-thirds of the people who lost their lives due to Florence were 50 or older, and one-third were in their 70s and 80s. That suggests emergency managers should reconsider how they communicate risk to elders.

A team from the University of Texas at San Antonio warned that emergency managers can rely too heavily on social media. Steve Davis, owner of All Hands, an emergency management consultancy, suggests a multimodal approach that includes wireless alerts, similar to a reverse 911 call. Pender County officials have applied for a license to broadcast on AM radio.

▪ Deaths were not concentrated in areas especially prone to flooding. The News & Observer layered the coordinates of the deaths for which it could get reliable location data over maps showing the 100-year floodplain. Just 20% were in areas labeled particularly risky.

Floodplain maps could be revised to reflect both new development and the expanded risk due to climate change. It’s important to remember that flood risk isn’t static, experts said.

▪ Storm surge was not blamed for any of the drowning deaths attributed to Florence, and only a quarter of Florence’s official victims died in counties bordering the Atlantic Ocean, at least 10 of which ordered a full or partial mandatory evacuation.

The heaviest rain dropped by Hurricane Florence was in Elizabethtown in Bladen County, more than 50 miles from the coast. The data, in combination with predictions that hurricanes could bring more rain than in the past, suggest emergency officials should be more prepared for long-lasting inland flooding.

▪ The inclusion of two suicides and the drowning deaths of two women who sought mental health care in the days after the storm suggest mental health supports could be improved. The suicides followed news about flooded homes; for one victim, it was the second flood in two years.

Research shows that it’s a lack of support after a disaster, rather than the disaster itself, that most often triggers suicide attempts, Kelman said. He proposes community-building as an antidote. “By bringing everyone together, we not only can recognize and try and deal with mental health difficulties openly, honestly and effectively, but we also prepare the community for disasters,” he said. “And then when a hurricane does come through, if someone has problems, they have a support network.”

Anna Douglas of The Charlotte Observer contributed reporting.

More from the series

NC after Florence: New evacuation zones, shelter plans

August 13, 2019

He died alone fleeing a hurricane. A year later, his body remains unclaimed.

August 13, 2019

They died in the storm. Why weren’t they counted?

August 13, 2019

Florence victims: They were mothers and sons, spouses and grandparents

August 13, 2019