Did political shaming shape who got the COVID vaccine?

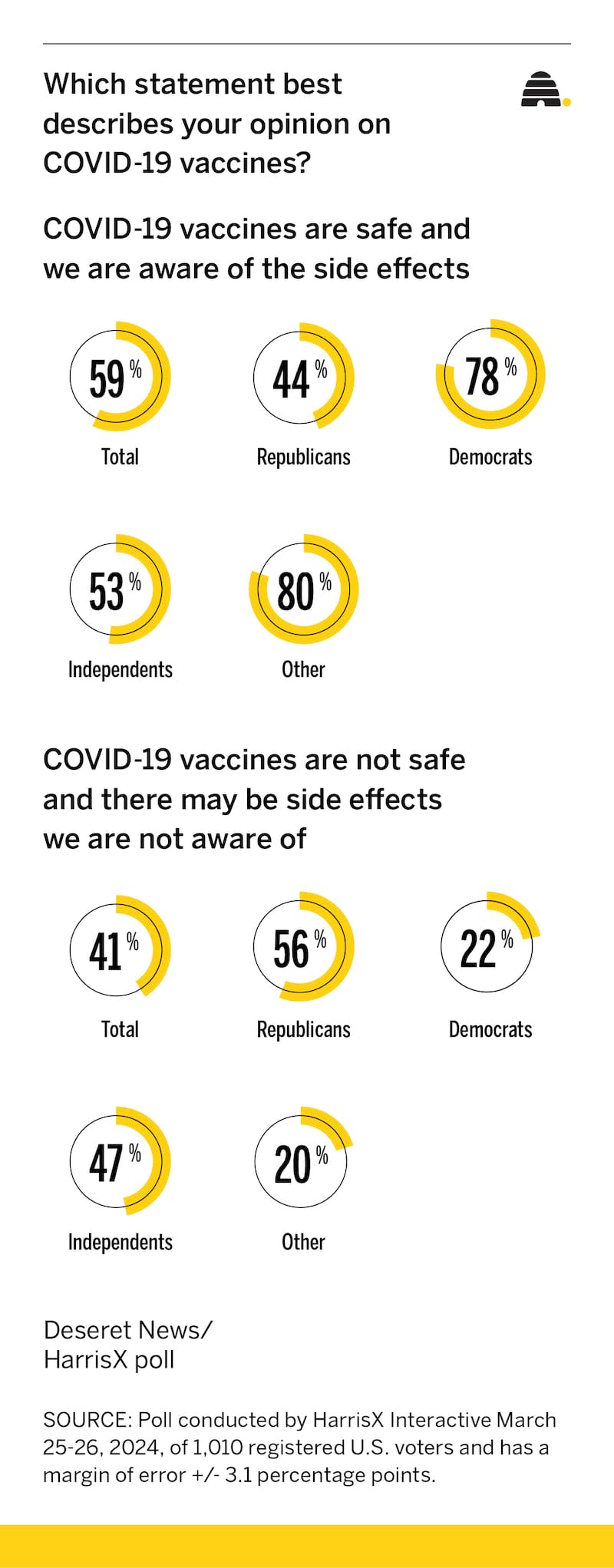

While most people believe COVID-19 vaccines are safe and their side effects are now clear, a new HarrisX poll conducted for the Deseret News finds a big partisan difference in how people view COVID-19 vaccine safety and effectiveness.

That finding is part of a larger tale about the divides that marked much of the public reaction to the COVID-19 pandemic and the challenges it posed, particularly in the early days when many people were dying, schools and businesses were closing, jobs were vanishing and public health officials sometimes contradicted not just each other, but even themselves.

While overall 59% of those polled are confident the vaccines are safe and their side effects now known, only 44% of Republicans agree, compared to 78% of Democrats and 53% of independents. The other 56% of Republicans and 22% of Democrats say COVID-19 vaccines are not safe and they may have side effects that haven’t been revealed.

The survey was fielded March 25-26 by HarrisX and included 1,010 registered U.S. voters. The margin of error is plus or minus 3.1 percentage points.

Public health experts believe confusing messaging built distrust early in the pandemic as the unfamiliar illness was ripping through communities, often with lethal results. And some think public shaming — attacking those with whom you disagreed or who questioned mandates like the orders to get a vaccine or else, including if you already had COVID-19 — played an oversize role that locked people into largely intractable positions.

Dr. Paul Offit, a pediatrician who directs the Vaccine Education Center at Children’s Hospital in Philadelphia and is a voting member of the National Vaccine Advisory Committee, thinks how closely — or whether — people followed public health vaccine advice has largely hinged on whether individuals had much interaction with a doctor or the health care system.

“People who got the vaccine as a general rule were people who were informed about it,” said Offit, who noted many people don’t have a lot of interaction with health care providers.

Dr. Leisha Nolen, state epidemiologist in the Utah Department of Health and Human Services, said age also played a role. Older people who were hit hardest in terms of severe COVID-19 were at greater risk of death, and more of them were willing to get vaccines.

Offit said because of Medicare, older Americans were also more likely to have a relationship with a health care provider who could answer questions.

Those who were used to getting flu shots were also probably more apt to be comfortable being vaccinated for COVID-19.

But all the experts consulted for this story believe partisan politics made a difference, too.

Public shaming

Folks who questioned the efficacy of vaccines or asked questions about public health pronouncements were sometimes shouted down. And they, in turn, often belittled others who held a different view.

The problem with shaming, according to Han Kim, a public health professor at Westminster College in Salt Lake City, is it’s a tool “that never worked in public health. It might have short-term benefits, but long term, it can cause a serious breakdown in trust toward not only public health, but toward each other.”

Disrespect and disdain for open dialogue came from multiple directions, not all political, Kim said. Public health experts shut down people who questioned what health officials saw as science and authority. Politicians used shaming to drive partisan wedges. And lots of folks simply disagreed with each other, each convinced the other was wrong.

“I probably participated in this as much as anybody else,” Kim admitted in a recent phone call. “That, I regret deeply. I think that’s going to be something that we’re going to live with for a while, because overall trust, not only in vaccines, but in public health, has declined dramatically I think.”

He said public health isn’t effective without trust in the institutions, and in COVID-19, some trust was breached.

A messy public message

Kim said people often expect public health to know all about diseases. “But when something new like this comes along, we’re trying to figure things out. I think we did an extraordinary job of figuring things out in a very short amount of time with COVID-19. The development of vaccines so fast is a perfect example. At the same time, any sort of mixed message definitely breaks down that institutional trust. And unfortunately, our messaging system was not very robust during COVID.”

He points to officials saying masks don’t work, then reversing and mandating them, as one example.

It’s not a challenge unique to COVID-19. Medical advice changes often as more is learned about diseases. But in a pandemic, with the stakes high and lives on the line, reversals create doubt.

“Politics had a big effect,” said Offit, noting that while that has long been part of vaccine discussion, COVID-19 raised the pitch. “What’s always been there, just never to this extent, is the notion of individual freedoms, personal bodily autonomy, individual rights. ‘I don’t want the government telling me what to do.’” There was “enormous political pushback” to vaccine mandates.

The mandates were the right thing to do in a public health crisis unfolding in real time, hospitals overrun to the point that nonemergency surgeries were canceled and people were “12 times more likely to be hospitalized or die in 2021 if you weren’t vaccinated than if you were,” Offit said. “By 2022, it dropped to six times more likely because there was more natural protection out there,” including natural immunity. “Look at it from a doctor’s point of view: Here you are, working double shifts, all hands on deck. People come into the hospital with an option to get a vaccine, which is free and don’t — yet they’re perfectly willing to avail themselves of the hospital service, the treatment part but not the preventive part.”

A mandate should not have been needed, Offit added, but he acknowledges “those mandates were tough. People were fired from their jobs.”

Nolen, Utah’s state epidemiologist, said contradictory public messaging didn’t help.

“I think there were a lot of things that impacted if people got vaccines — and a lot of voices telling them different things,” she told the Deseret News. “It was really unfortunate we got such confusing messaging from different leaders, different organizations, different community groups. I think it made it hard for people to know who to trust and who to lean to when they were making those choices for themselves and their families.”

Utah’s version of the national Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Survey showed political philosophy had at least some influence on who took the vaccine or planned to, she said. “In public health, we really don’t want that. We want to do what’s right for everybody” without “political sway to it.”

Nolen and Kim both believe that public health experts learned from COVID-19 that how a message is presented really matters. Officials had figured people would follow their advice.

Instead, they learned that public health needs to work with different communities “to make sure we talk in a way that resonates with them, that highlights their values. And we all have different values,” said Nolen. “We all have different risks and to tell someone to just do this because of the science of it isn’t going to work. Hopefully, public health has learned through this pandemic that we need to think more actively about how we’re talking about things to whatever population we’re talking to.”

Another challenge is how the public health system works, Kim said. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is set up to provide information, but much power rests with state and local health departments, so sometimes messages are very mixed.

The good news, according to Nolen, is that COVID-19 has been around a while, knowledge has grown and those giving the public message are more clear about the disease’s mechanics and what people should know.

Kim agrees. “We learn more from our mistakes than from our successes,” he said. “I wish everyone had more patience and understood science and, again, didn’t think so black and white, but it seems to be the environment we live in.”

What about natural immunity?

Offit differed with many of his peers on the question of natural immunity for COVID-19. He voted not to mandate vaccines for people who’d recently had COVID-19 infection. He was outvoted.

“It’s certainly true that if you’ve been naturally infected, you’re going to be protected against at least severe disease. Vaccinated or naturally infected or both, you develop an antibody response against at least mild disease for about three to six months. You also develop memory cells: memory B cells which make antibodies and memory T cells which can kill a virus and are much longer lived,” he said.

“The question then is how much longer lived. A year? Two? 10? I think we’ll find out.” Offit said he had three doses of vaccine, the last in November 2021 and had COVID-19 once. He has no health problems, so he figures he has plenty of memory T cells to protect him from severe disease. “I don’t know how long, but we’ll see.”

Experts have long told the Deseret News that not knowing who had COVID-19 unless it was lab confirmed or how long natural immunity lasts drove vaccine mandates. Most people who got sick dealt with it at home without lab confirmation.

Kim sees another issue: “One could argue natural immunity’s better than vaccine-induced immunity, other than the fact that you actually have to get the disease, which is never a good thing. I would prefer a vaccine than to actually get the disease.”

Is the vaccine safe?

In the poll, more men view the vaccine as safe, the side effects known, compared to women, 62% versus 56%.

The survey also found age differences. The vast majority of people 65 and older view the vaccines as safe (71%). That’s true for 54% of those ages 18-34, 52% of those 35-49 and 59% of those 50-64.

Hispanics in smaller shares are convinced the vaccines are safe and side effects known at 52% compared to both whites and Blacks, which each come in around 60%.

More than two-thirds of those with a four-year college degree or more believe the vaccines are safe, compared to 54% of those with less education.

By income, there’s more doubt among people with household incomes below $75,000 (57% say safe) compared to those with higher incomes (62% say safe).

Southerners are more skeptical than other regions of the country. They’re divided about 50-50, compared to those in the West (67% say safe), Northeast (64%) and Midwest (60%).

Who got a vaccine?

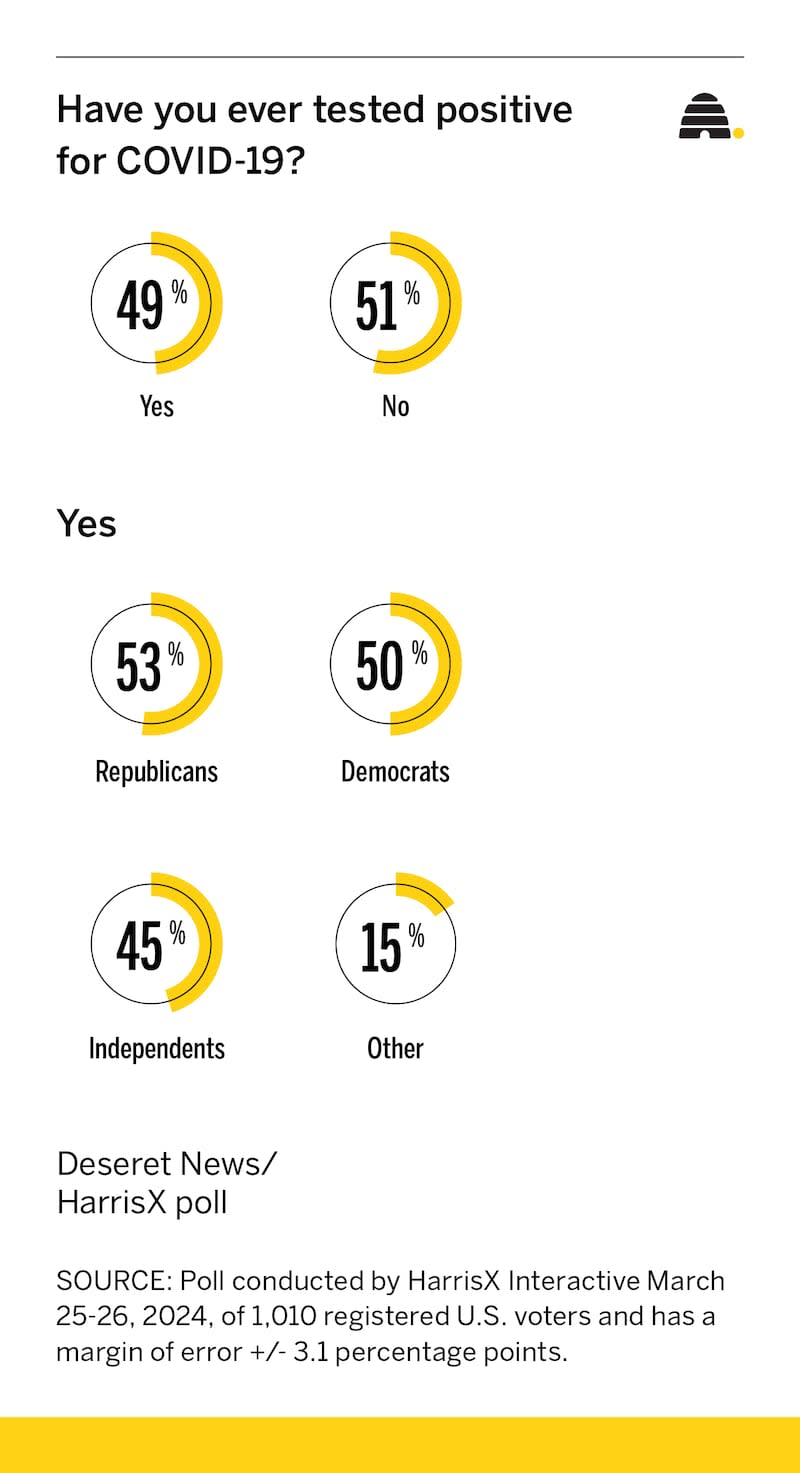

The survey found big differences in uptake of vaccines, sometimes based on politics, but more commonly on age. The youngest cohort, 18-34, is more likely to say they’re unvaccinated (29%) than those 65 and older (12%). Overall, 28% of Republicans say they are not vaccinated, comparable to 26% of independents, but a far cry from 12% of Democrats. More women (24%) than men (29%) say they have never had a COVID-19 vaccine. Overall, 28% have never been vaccinated.

About one-third overall got a booster in the past six months.

The survey found 3 of 10 Democrats have had at least four COVID-19 shots, compared to 1 in 4 Independents and 1 in 7 Republicans.

How much of the uptake is really about politics or ideology? Experts admit they’re still not sure, since other factors also made a difference

Nolen said that most public health experts, herself included, expect COVID-19 to move to “the flu model,” with a seasonal vaccine to protect folks. That depends, of course, on whether there are drastic mutations to the virus that make it more dangerous again.

“I think if things continue where it’s a slower mutation with nothing dramatic, it will be a yearly dose that will be updated for the most recent viruses,” she said. “If we have a big, dramatic change, we might need to get another booster that’s going to be specific to that really dramatic version.”