Did Andy Warhol predict his own death?

In January 1987, while opening an exhibition of his work in Milan, Andy Warhol began suffering from terrible abdominal cramps. The artist had no faith in conventional medicine – when his friends were dying during the Aids epidemic, he wore a crystal pendant around his neck.

But the pain was so intense that when he returned to New York he sought professional help. His doctor diagnosed an infected gallbladder that was in danger of becoming gangrenous, and recommended removing it at once.

Warhol had misgivings – “Oh, I’m not going to make it,” he told friends – but later that week, after locking valuables, including his will, inside a safe in his Upper East Side mansion, he checked into hospital under the pseudonym “Bob Robert”.

The surgery was scheduled for the next day, a Saturday. “It’s a painful part of my memory,” recalls Vincent Fremont, the vice-president of Andy Warhol Enterprises, Inc., who managed the artist’s studio, known as the Factory. “We learnt too late that you should never have an operation done on a weekend.”

The operation itself did not throw up any complications. But during the night that followed Warhol was not properly cared for and early the next morning it was apparent that things had gone terribly awry. By 5.45am, he had turned blue. At 6.31am he was pronounced dead.

The official cause of death was a heart attack, suffered while he was asleep. “It was a perfect storm of things that went wrong,” says Fremont, speaking from New York. “Andy shouldn’t have died. He was 58. He was in good health. He might have been too skinny, but that was it.”

Although Warhol’s death 30 years ago was unexpected, the artist, whose fatalistic streak had grown increasingly prominent after a disgruntled acquaintance shot him in 1968, had seemed almost to foresee it. “Andy was a very intuitive person,” Fremont says. “So perhaps he did have a sixth sense about his own mortality.”

Certainly, during the last decade of Warhol’s life, a new note of premonitory darkness cast its shadow over the body of work that he produced. In those years, death – always an important theme for Warhol – became, arguably, his principal subject.

A Warhol exhibition, which was on last year at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, illustrated this overlooked stage in the artist’s life. With more than 100 artworks, lent from the private collection of the Florida -based British hedge fund manager Andrew Hall and his wife, Christine, the exhibition, which spans the artist’s career, is especially strong on the Eighties.

In part this is because Warhol’s late works used to be ridiculed or ignored, so for once they were relatively affordable. In particular, the Halls amassed an enviable selection of the striking black-and-white paintings that Warhol produced in 1985-86.

In these sinister pictures, Warhol returned to his origins as a Pop artist, by replicating banal, throwaway newspaper adverts for everyday items. These included a cheap, illuminated figurine of Christ, with a price tag of “only $9.98”, and a floating, halo-like hamburger, which appears to bestow ready-made salvation, like a kind of fast-food saint.

The black-and-white pictures epitomise the tenebrous tone of Warhol’s output during his final years. In 1978, he also began his haunting series of Shadow pictures: enigmatic expressions, perhaps, of his ghostly role as America’s recording angel. Then, in the early Eighties, he worked on new, menacing paintings depicting handguns and kitchen knives. The violence of contemporary American life was taking centre stage.

A little later, around 1985, he created a powerful painting in which the word “Aids” was spelt out in block capitals. “With the arrival of Aids, we lost so many great friends,” Fremont says. “It was this kind of apocalypse – almost like a war, when you read in the papers the list of dead and wounded every day – that affected him.”

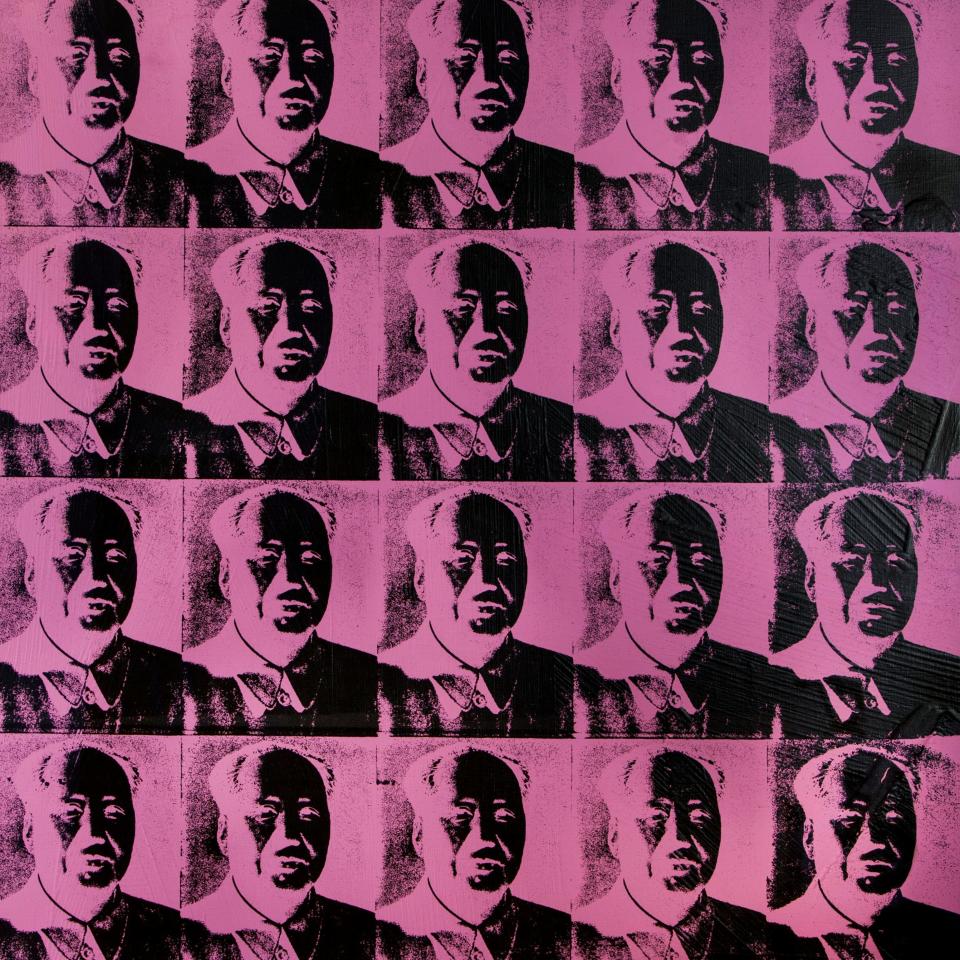

At this point, however, Warhol was considered a spent force within the art world. The heroics of the Pop years during the Sixties were behind him. Instead, he was apparently devoting all his energy to being a successful society portraitist. He was out every evening at hip nightspots such as the Mudd Club and Studio 54.

The next day, his fashionable friends would assemble at the Factory so Warhol could snap them with his Polaroid camera. He then turned his instant pictures into bright silk-screen portraits, characterised by intense, acidic colours. The format was always the same (40 x 40in), with prices dropping from $25,000 for the first canvas to $5,000 for the fourth.

At the time, people carped that Warhol was a sell-out. In 1974, he bought a six-storey town house on New York's Upper East Side. By the end of the decade, his portraits were bringing in as much as $2 million per year. Yet these supposedly superficial pictures now have their defenders.

“They chronicle the age,” says Norman Rosenthal, who worked with Warhol in the Eighties, and has curated the Ashmolean exhibition. “Andy was as great a portrait painter as Joshua Reynolds was in his own time.”

Still, when Warhol exhibited his paintings of dollar signs in 1982, even his long-time dealer, Leo Castelli, was embarrassed. Castelli relegated the show to the basement of his Greene Street gallery in New York, and felt perversely vindicated when not a single one of the paintings sold. “Nobody had a good word to say for Andy,” recalls the British art dealer Anthony d’Offay, who also worked with Warhol in the Eighties.

In 2009, d’Offay put together a large collection of paintings and drawings by Warhol, including one of his Dollar Signs, and gifted them to the nation as part of the touring Artist Rooms project, which will have its own dedicated gallery when the redesigned Tate Modern opens this summer. “I remember the horror that the Dollar Signs were greeted with [in the Eighties],” he says. “People said he was a has-been. But now the pictures look prophetic.”

It was around the time of the Castelli exhibition that d’Offay approachedWarhol. “I said, 'We’d love to show you in London’. He said, 'Great’.” When d’Offay asked what Warhol would like to exhibit, the artist replied: “That’s up to you – I’ll do whatever you want.” His response might sound cynical and lazy – the gun-for-hire attitude of a commercial artist. Yet to d’Offay, it was a sign of Warhol’s singularity: “What other artist in the history of the world has said: 'You tell me what to do, and I’ll do it’?”

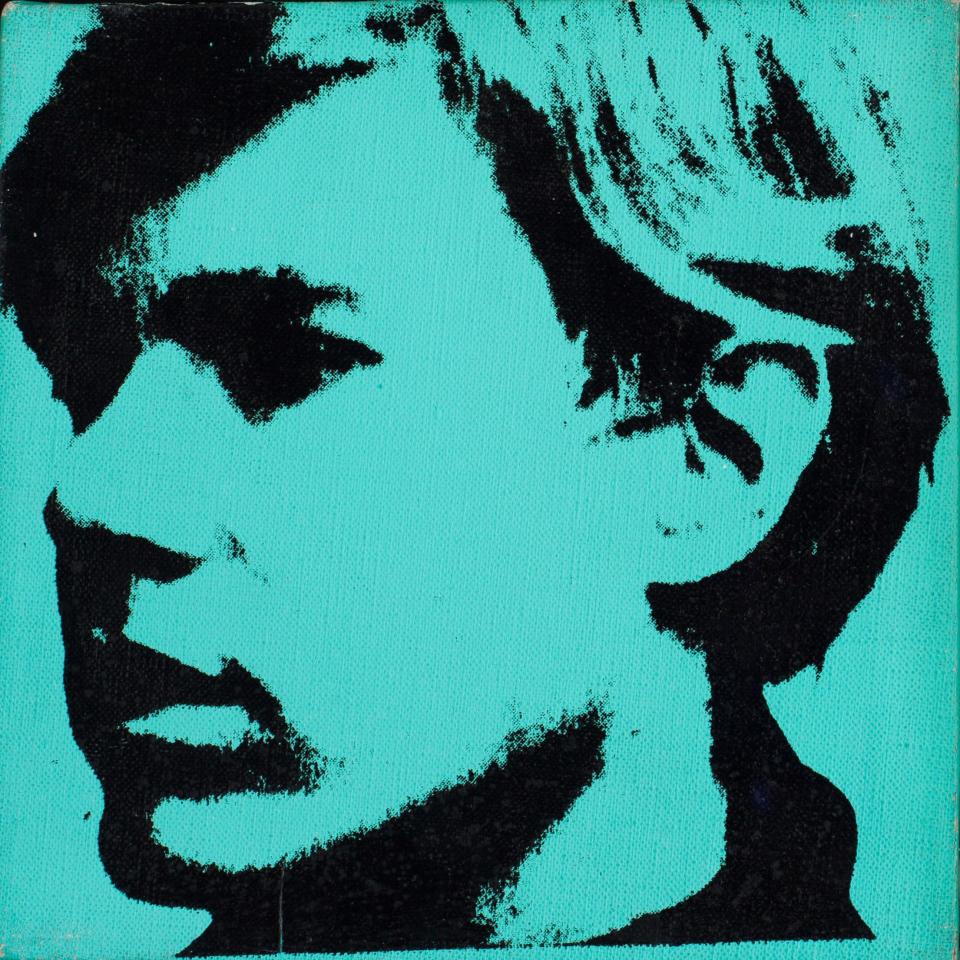

A few years went by – “and then it came to me in a flash”, d’Offay says. “I suddenly thought, my God, this is the only guy in the second half of the 20th century who has really cracked how to make a portrait. How long is it since he has done a self-portrait?” Two days later, d’Offay was on a Concorde to New York. Hearing his suggestion, Warhol became “supercharged” and set to work.

The result was his seminal exhibition of self-portraits, now known as the Fright Wig series, on account of Warhol’s spikily dishevelled toupee. It opened at d’Offay’s gallery in London in 1986. “I think we sold five of them to museums, including the Metropolitan [in New York],” d’Offay says with a smile. “That was pretty exciting for Andy.” After a decade in the doldrums, Warhol could chalk up a hit.

For Fremont, the Fright Wigs were the culmination of a late surge of creativity. In the Eighties, the artist had worked as a male model, directed music videos and even produced his own talk show on cable television. His series AndyWarhol’s Fifteen Minutes premiered on MTV in 1986.

D’Offay had also come up with another project for the artist: to make a series of pictures of Samuel Beckett. “Andy called me, saying, 'I’m going into hospital on Friday, and in a week’s time I’m flying to Paris. Beckett is very keen. I’ll take a lot of photographs and I’ll paint an exhibition for you, Anthony, in really pretty colours’.” D’Offay pauses. “Then he died.”

Although surprised, d’Offay wasn’t deeply shocked – because he knew that Warhol’s final spate of creativity had coincided with a preoccupation with death. “He was making a body of work about how close death is,” says d’Offay, who points out that the photograph Warhol initially wanted to be the source for the Fright Wig paintings looked uncannily “like a death mask”. He says: “I remember being in the Factory with Andy, inside a tiny lift. I looked at him, while he was looking ahead, and his face was deadly white. I saw Death.”

Warhol, of course, couldn’t actually see into the future. But towards the end of his life, his otherworldly detachment arguably revealed greater depth of thought and feeling than he is often credited with.

For Fremont, Warhol’s obsession with the surface of things “was just a smokescreen. Andy was always given the title of Pop artist, but he was much more than that: he was a conceptual artist, a colourist, an installation artist, and a visionary. Yes, he was more complex than he let on.”