Detroit abounds in the work of a local poet who became world famous

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

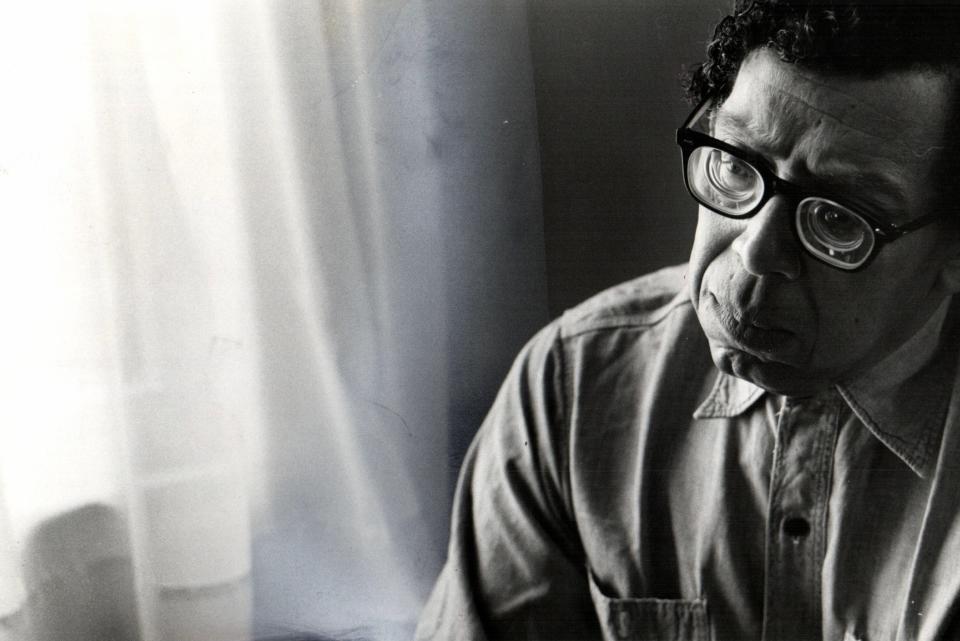

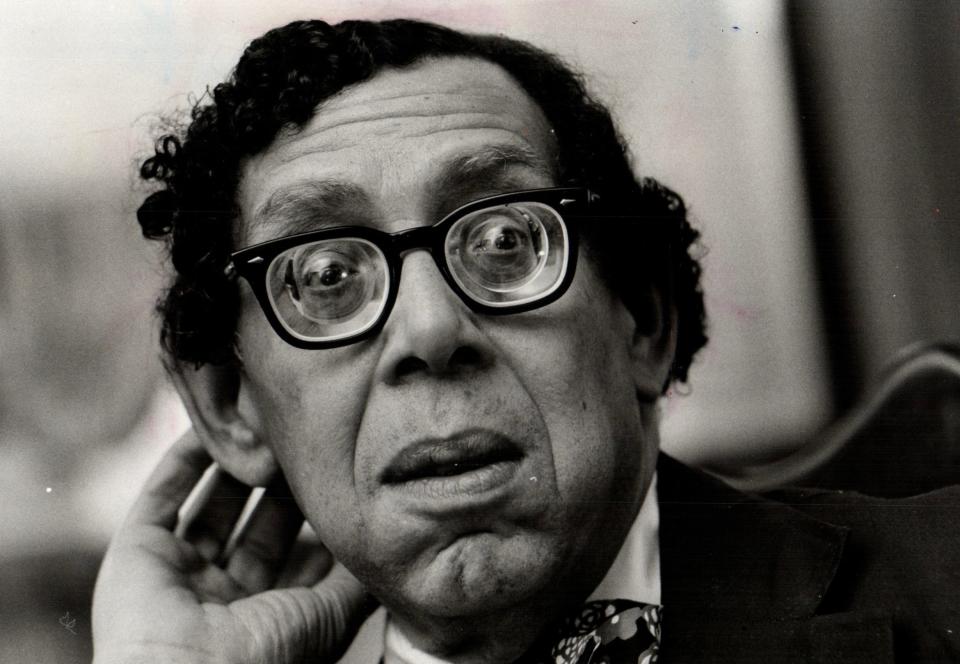

When Langston Hughes visited Detroit in April 1937, he was already at 36 a celebrated American writer, leader of the Harlem Renaissance.

He came to the city to see friend Elsie Roxborough’s production of his play “Drums of Haiti” at the YWCA, where Comerica Park stands today.

Probably no one in the cast wanted to meet Hughes more than 23-year-old Robert Hayden, an aspiring poet who had grown up nearby in Paradise Valley.

Hughes could not have known that Hayden would someday become poet laureate, read at the White House, win international recognition and be commemorated on a U.S. postage stamp.

Detroit informed Hayden’s art. St. Antoine, Beaubien, Belle Isle, Paul Robeson at Cadillac Square, Joe Louis, the librarian who saved books for him, double features at the Dunbar — Detroit references abound. Until the end, Hayden remained inspired by his childhood. When he died, he was at work on “Elegies for Paradise Valley.”

But back to 1937.

A tough childhood

Young Robert Hayden had been savoring Langston Hughes’ poems and unconsciously mimicking his voice while seeking his own. Backstage, Hayden was costumed as a voodoo priest in cape and feathers, his face coated in dazzling colors.

“This is Bob Hayden,” said Elsie Roxborough.

Langston Hughes undoubtedly noticed Hayden’s thick eyeglasses. Everyone did. His eyesight had been terrible since childhood, and his prescription lenses created a swirling 3D effect when you faced him. It was Hayden’s poor vision that led him to literature. Unable to play sports and wanting to avoid name-calling bullies, he took refuge among books. By age 5, he could read.

Roxborough arranged for Hughes and Hayden to have lunch. Hayden brought his poems. A few had been published locally in The Detroit Tribune and the journal Phenix. While not overly enthusiastic, Hughes encouraged Hayden. Afterward, he probably thought their goodbye was final. It wouldn’t be.

Born Asa Sheffey in 1913, Hayden had a tumultuous early life. His parents divorced, and his father departed. Months after, his mother moved to Buffalo, leaving her toddler with the Haydens, neighbors in the Beacon-Beaubien area. They changed his name — not legally, he discovered later — and raised him as their son. The Haydens’ strict-Baptist household simmered with anger and jealousy. Mr. Hayden found Robert peculiar and unmanly.

“Worse than the poverty were the conflicts, the quarreling, the tensions that kept us most of the time on the edge of some shrill domestic calamity,” Hayden recalled in 1975. “We had a terrible love-hate relationship with one another, and dreadful things happened I can never forget.”

Writing eased his pain.

The 1930s saw Hayden graduate high school; study at City College (later renamed Wayne State); write poems, plays and newspaper columns; direct and act in amateur productions; and interview formerly enslaved people for the Federal Writers Project.

In 1938, he became a graduate student at the University of Michigan, where he met rising playwright Arthur Miller and won his first Hopwood Award. The second came in 1942. By then, he had married pianist Erma Morris, debuted his first book (“Heart-shape in the Dust”) and been published in an anthology and The Atlantic magazine.

A bit of serendipitous fortune put Hayden at Michigan as W.H. Auden, one of Britain’s foremost poets, arrived to teach for one school year. Auden, at 34, rumpled and eccentric, awed Hayden by reciting poems from memory in German and Latin. “We all had read his books.” Hayden recalled. “We knew that he was brilliant.” When Hayden’s daughter Maia was born, Auden dropped by to welcome her into the world.

A friendship with Langston Hughes

Hayden’s life looked charmed. He accepted a teaching position at Fisk University in Nashville, where he would remain for 20 years. But soon he felt stuck. His successes stalled. Doubts and depression plagued him.

He shared his troubles with Langston Hughes, who had become a friend. Their letters are archived at Yale University.

“The few things I have done are utterly discouraging,” he wrote in 1949 of recent work.

In 1955: “I seem doomed to be a pamphlet poet, a periphery poet.”

In 1958: “I have really been discouraged.”

A letter to another friend revealed his greatest fear. I discovered it among Hayden’s papers at the National Bahai Archives in Wilmette, Illinois. “Maybe I have been a great fool all these years to imagine that I could accomplish anything in literature,” he confided.

His fortunes changed again in 1962, when his second book, “A Ballad of Remembrance,” was published — 22 years after the first (a couple “pamphlets” appearing between). “Ballad” included two of what would become his most lauded poems, “Those Winter Sundays” about his foster father and “Middle Passage” about the slave trade. The book brought wide recognition, winning grand prize at the World Festival of Negro Arts in Africa.

More books and honors followed — poet-in-residence, National Book Award finalist, University of Michigan professorship, Academy of American Poets fellowship — culminating in his 1976 Bicentennial appointment as Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress, known now as poet laureate.

“I wish I had met Robert Hayden, but I never did,” Robert Pinsky, poet laureate 1997-2000, told me in an email. “He is a poet I honor for his masterful, profound work and for his greatness of spirit, demonstrated in poems such as ‘Middle Passage’ and in all accounts of him as a person.”

In January 1980, Hayden read at the Carter White House with other prominent American poets. A month later, the University of Michigan paid tribute. Poets came from across the country. Stricken by a virus and battling cancer, Hayden could not attend. Afterward, friends stopped at his Ann Arbor home. He exuded a joyful spirit. But the next day, Hayden died at 66.

Friends described him as kind, complex and quick to tears and laughter — “sensitive, almost fragile,” according to a biographer, John Hatcher.

Hayden’s work is precise and vigorous. He mastered various styles and structures. His subjects touched on the historic, personal and more.

Dr. Melba Joyce Boyd, a poet and distinguished professor of African American Studies at Wayne State, grew up in Detroit. Hayden was one of her heroes.

“Robert Hayden was a literary genius,” she said in an email. “Poverty and racism could have sabotaged his life and corrupted his thematic purposes. But Hayden subverted these systemic forces with poetic grace and aesthetic courage that has nurtured generations of poets.”

Hayden is still appreciated. He is still in the conversation, still read, published and quoted 44 years after his death, even surfacing in popular culture, as when Stephen Colbert recited one of his poems on television. Ann Arbor recently designated his home a historic site, and an effort is underway to name the local post office in his honor.

At nearby Fairview Cemetery, Robert Hayden’s grave marker is easy to miss: a simple slab snug in the ground. But other poets find it.

Keith Taylor, a retired Michigan professor, visits occasionally. Sometimes he brings fellow writers. “We will often read a poem out there,” he said. “I’ll admit that in my own old age, I get a little teary over Hayden’s grave.” Though he never met the man.

“Hayden's poems cut across all the lines of race and class,” said Taylor. “And even of time.”

Tom Stanton is author of several nonfiction books, including “Terror in the City of Champions” and “Ty and The Babe.”

This article originally appeared on Detroit Free Press: Detroit abounds in work of Robert Hayden, local poet who became famous