DeSantis’ 2023: More Than $160 Million Spent To Buy A Collapse In The Polls

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

A year after Ron DeSantis led Donald Trump in some 2024 presidential primary polls, and with just weeks to go before the first ballots are cast, the Florida governor is already explaining how Democrats conspired to stop him: by repeatedly charging the coup-attempting former president with breaking the law.

DeSantis’ campaign and super PAC have spent more than $160 million to boost him, and he spent the better part of 2023 on the road. But, he now says, it may not have been enough to overcome the advantage he believes Trump received from getting indicted four times.

“If I could have one thing change, I wish Trump hadn’t been indicted on any of this stuff,” he told the Christian Broadcasting Network last week. “It sucked out a lot of oxygen.”

The line is working, at least with some.

“The race was decided totally out of their control,” said one DeSantis donor and supporter who spoke on condition of anonymity. “Trump got indicted. And indicted and indicted and indicted. The race was over after the first indictment.”

Other Republicans are less charitable as they describe DeSantis’ steady decline over the year ― which began with GOP donors giving him unsolicited six- and seven-figure checks, saw him spend far more time and energy attacking the Walt Disney Co. and the nation’s top doctor during the COVID pandemic than he ever did taking on the front-runner in his race, and ended with DeSantis some 40 points behind Trump in national polls.

“He started the primary on third base and stole second,” said David Jolly, who served with DeSantis as a fellow Republican member of Congress from Florida. “We’ve now witnessed one of the most expensive and embarrassing collapses in Republican history.”

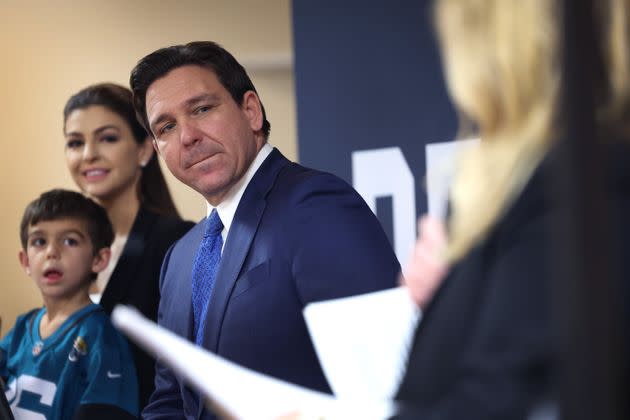

Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis (R), with his family by his side, speaks to guests during the Scott County Fireside Chat at the Tanglewood Hills Pavilion on Dec. 18 in Bettendorf, Iowa.

Fergus Cullen, a former New Hampshire Republican Party chair, wondered about DeSantis’ apparent strategy of trying to win over the roughly one-third of primary voters who are “only Trump,” rather than the two-thirds who are open to someone else.

“He tried to ‘out-Trump’ Trump among Trump supporters instead of going for the ‘maybe Trump/move on from Trump’ voters, and it was a fatal strategic choice,” Cullen said.

DeSantis’ campaign did not respond to HuffPost’s queries.

The Florida governor’s various missteps over the year ― as well as those of his campaign and his supporting super political action committee ― have been well documented, from the time he called Russia’s invasion of Ukraine a “territorial dispute” to the mass campaign layoffs just two months after he officially began his run to the recent dysfunction at the super PAC, Never Back Down.

Yet all of these things might have been ignored, or in some cases might not have happened at all, if DeSantis had been on track to win the Iowa caucuses and New Hampshire primary next month. If recent polling is accurate, though, DeSantis is likely to finish only a distant second in Iowa and fourth or fifth in New Hampshire.

What’s more, the gaffes, the internal squabbles and even his unwillingness to use the legal consequences of Trump’s behavior against him pale beside DeSantis’ fundamental flaw: his inability to get enough Republican primary voters to like him.

Polling shows that his numbers were strongest before he actively began campaigning for president in late May, and that the more voters saw of him, the less inclined they were to support him.

“The idea of ‘a’ DeSantis was appealing, but the reality of ‘the’ DeSantis was repellent,” said Mac Stipanovich, who served as chief of staff to Florida Republican Gov. Bob Martinez in the 1980s, and has been involved with GOP campaigns in the state for decades. “It is telling that his favorite president is Calvin Coolidge, the avatar of anti-charisma in politics.”

“When you come across as a mean person who shows little empathy for the real concerns for citizens, and who always wants to make sure everyone in every room knows you think you are the smartest person there, it doesn’t go over all that well,” said Steve Duprey, a former Republican National Committee member from New Hampshire. “Focusing on Disney, wokeness, a little hippie college in Sarasota, and an abortion ban out of sync with most of America, instead of on the economy, the debt, the border, isn’t a winning formula.”

“Other than that,” Duprey said, “he’s nailing it.”

‘Just Not Likable’

That DeSantis had trouble winning over voters in the restaurants and living rooms of Iowa and New Hampshire is perhaps not surprising. Unlike most politicians who have won statewide races, DeSantis never had to acquire the “people” skills that are usually necessary for such a feat.

In 2018, as Adam Putnam, the establishment favorite to win the GOP nomination for Florida governor, visited countless local party meetings up and down the state, DeSantis conducted his primary campaign largely on Fox News, where he had become a familiar, incendiary voice since his arrival in Congress five years earlier.

Those appearances also made him known to Trump, an avid TV watcher, who eventually gave DeSantis his endorsement. It let DeSantis vault past Putnam, the state’s agriculture commissioner, and win the primary easily.

Trump’s backing, combined with an ongoing FBI corruption investigation into his Democratic opponent, Andrew Gillum, were just enough for DeSantis to squeak to a win of less than half of a percentage point.

Stipanovich said that while a margin that narrow might have humbled some, it apparently had the opposite effect on DeSantis.

“Almost immediately, I’m certain that he wanted to be president of the United States. Not someday, but soon,” Stipanovich said.

What’s more, DeSantis quickly jettisoned the team that had won him the governor’s mansion and instead surrounded himself with young admirers who believed the key to success lay in picking fights with journalists and “woke” groups.

“He got too much positive reinforcement for being negative. And he became addicted to it,” Stipanovich said.

After a year in office marked by generally mainstream conservative policies, DeSantis moved to a persona focused on culture wars and retribution, said one top Republican in Tallahassee who spoke on condition of anonymity.

“They think they’re the smartest people in the room. And they think Jesus is on their side,” the Tallahassee Republican said. “Who was he? Was he for Trump? Was he against Trump? Was he courting Trump voters? Is he more practical, sensible? Or he is a right-wing nut? I don’t know. But he’s just not likable.”

DeSantis’ social awkwardness ― an apparent difficulty holding eye contact, a tendency to inflame combative conversations rather than de-escalate them, a seeming inability to empathize ― may not matter in softball interviews with conservative media. But it has proven a tough challenge to overcome in the small-group interactions that Iowa and New Hampshire voters have come to expect.

“To me he never looked very happy,” said one Iowa political operative and supporter, who spoke on condition of anonymity.

“A few of my congressional staff worked for him, and we all said the same thing,” said former Illinois Rep. Joe Walsh, who unsuccessfully ran against Trump in the 2020 presidential primaries. “He’s just weird. Doesn’t know how to just normally interact with people.”

Defending An Accused Criminal

Even if DeSantis had proven charming and personable on the campaign trail, it’s unclear whether it would have been enough for him to supplant Trump, given a key choice the governor made in August 2022, just hours after the former president announced that Mar-a-Lago, his South Florida country club, had been raided by the FBI.

Like so many other Republicans, DeSantis fell in line behind Trump and attacked law enforcement and Justice Department prosecutors ― before having any real idea of the potential crimes implicated.

“The raid of MAL is another escalation in the weaponization of federal agencies against the Regime’s political opponents, while people like Hunter Biden get treated with kid gloves,” DeSantis said in a Twitter post the evening of the FBI search.

The DeSantis donor said the governor had no choice but to defend Trump after previously getting excoriated by Trump followers for telling an interviewer that he had no familiarity with paying hush money to porn stars and therefore could not comment on an ongoing investigation into Trump by New York prosecutors.

But unlike most Trump supporters, who have little knowledge of or experience with the judicial system, DeSantis is a trained naval JAG officer who worked in that capacity as a federal prosecutor in Florida. That experience, in theory, should have given him an understanding of what it takes to get a judge to approve a search warrant ― particularly when the target is a former president.

Whit Ayres, a longtime Republican pollster who worked on DeSantis’ 2018 run for governor, said DeSantis could have released a statement pointing out that the allegations underlying the search warrant were serious, that he hoped they were not true, and that Trump was innocent until proven guilty and would have his day in court.

“Something like that would have been more appropriate, I think,” he said.

But DeSantis instead continued to attack prosecutors, helping Trump push his continual claims of persecution and victimhood. Months later, when Manhattan District Attorney Alvin Bragg announced the first indictment of Trump for falsifying business records to hide a $130,000 hush money payment, DeSantis said he would refuse to extradite Trump to New York ― thereby vowing to violate the Constitution to protect an accused criminal.

Since then, Trump has been indicted in Washington, D.C., and Atlanta for his actions leading up to his Jan. 6, 2021, coup attempt, and in South Florida for refusing to turn over secret documents he improperly took with him to Mar-a-Lago from the White House, which was the basis for the FBI raid.

In all, there are 91 felony charges against Trump, the most serious of which could send him to prison for decades. Nevertheless, DeSantis still argues that the prosecutions are all inappropriate. Even as Trump mocks DeSantis for supposedly eating pudding with his fingers and wearing lifts in his boots, DeSantis’ harshest criticisms of Trump have been for his refusal to participate in the party’s primary debates.

One Republican consultant, who spoke on condition of anonymity, said DeSantis’ decision to help Trump vilify prosecutors, rather than figuring out a way to use his opponent’s criminal charges against him, is mystifying. Why, after all, should primary voters view Trump’s actions as disqualifying if even his political rivals do not?

“If you can’t learn from history, you can’t change the future,” the consultant said, pointing out that Trump’s Republican rivals similarly treated him with kid gloves in 2016 until it was too late. “The only way to take out Donald Trump is to take him on.”