Deputies did nothing as woman was raped for hours near Boca. When she screamed, they debated why

Tzvi Allswang prepared for his home therapist’s upcoming visit with care to avoid problems that had stopped him the last time he had raped someone.

He had duct tape for her wrists.

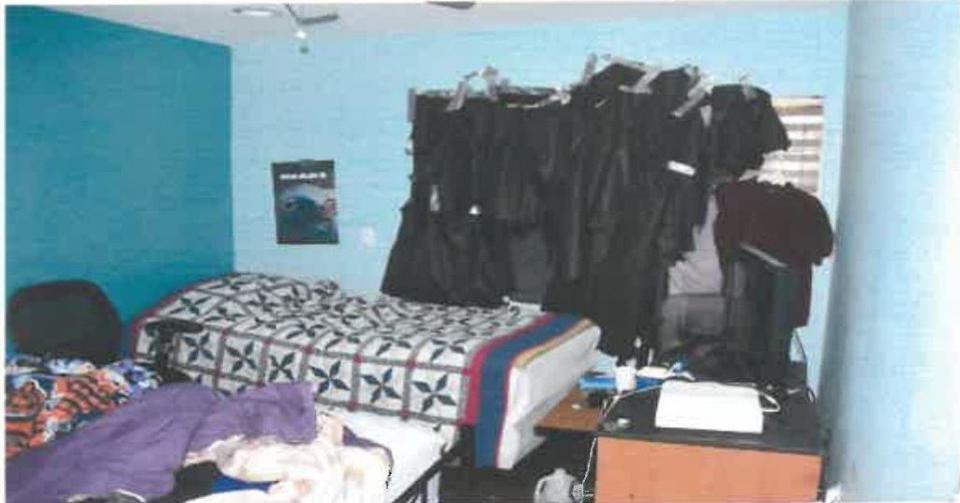

He bought black plastic tablecloths to cover the front windows.

He scheduled the visit to ensure his family would not interrupt him.

He arranged to have 24 hours to do whatever he wanted to her.

Still, the night of terror he had planned for July 1, 2022, could have ended when deputies found the therapist’s car at his house.

More: Boca-area man pleads guilty to attack on therapist in his home

It did not end then, or even when they heard her scream.

Instead, Palm Beach County Sheriff’s deputies ignored evidence for six hours that a missing woman was in danger and left her to be tortured, raped and terrorized, a Palm Beach Post investigation has found.

Deputies who came to the house where the therapist was held captive failed to run routine checks that would have revealed Allswang’s previous violent sexual assault conviction. They ignored pertinent facts shared by people who knew the woman. They overlooked repeated clues that the therapist was inside the house against her will.

When they heard her scream, they debated whether they had heard a cry for help, or a sound of pleasure from consensual sex.

By the time deputies got into the house in the morning, Allswang was holding a knife against her throat. He did not drop it until a deputy shot him.

Allswang survived the shooting. He remains in jail. In March, he pleaded guilty to attempted murder, kidnapping and five counts of sexual battery, each of which carry a potential penalty of life in prison. His sentencing is scheduled for June.

The therapist also survived and recounted everything Allswang did to her.

Two years later, sheriff's internal investigation remains open

The deputy’s shooting of Allswang was justified, the Palm Beach County State Attorney’s Office and the Florida Department of Law Enforcement had concluded by the spring of 2023.

Nearly two years after the deputies’ decisions prolonged the therapist’s terror, however, the sheriff’s office internal investigation remains open, in spite of state law requiring such investigations to close within six months if they are to lead to disciplinary action.

The lessons the night offered the department and its deputies have not led to any form of reprimand, discipline or training.

Citing the open investigation, PBSO leadership has declined to respond to The Post's questions about the deputies' decisions that night.

For mental health workers, home visits bring risks

Of 23,000 workplace assaults between 2011 and 2013, 75% happened to healthcare and mental health workers. In 2019 and again in 2022, U.S. congressional bills citing that data proposed that employers be required to put protocols in place to better protect workers paying home visits.

The therapist’s employer would tell deputies the therapist didn’t usually go into the home unless other people were there.

She had told her domestic partner that a “weird dynamic” in the house worried her. Colleagues had warned her of the client's troubled history.

These facts told a story that the woman’s partner would spend hours begging deputies to listen to.

The Post is not identifying the therapist because it doesn’t identify victims of sexual assault.

Tzvi Allswang: A record of sexual violence

Tzvi Allswang’s family fit in with the Orthodox Jewish community surrounding them in suburban Boca Raton. They lived in a spacious home on Larkspur Trail that Elliot, a financial adviser, and his wife, Margo, bought in 2000.

With their neighbors, they worshiped at a synagogue they could walk to. They faithfully observed their sabbath — Shabbat — from sundown every Friday until after dark Saturday night. They followed the biblical commandment to keep the Sabbath day holy, as a time of spiritual reflection, forgoing the use of technology. During Shabbat, they put aside their phones.

When Margo Allswang died in 2009, neighbors remembered her as a pillar of her faith. They hoped her memory would comfort her children: two older daughters as well as Tzvi, then 7 years old and his twin brother.

By the summer of 2022, the girls had left and started their own lives. Tzvi’s twin worked as a camp counselor. Tzvi Allswang, tall and thickset, had grown into a dangerously disturbed young man.

At 17, he had repeatedly raped a classmate after wrangling an invitation to “hang out” at her home.

The classmate’s account of that 2019 attack would turn out to be, in striking ways, similar to what happened to the therapist.

Allswang pleaded guilty to lewd and lascivious battery and as a juvenile, was sentenced to probation.

Tzvi Allswang and his therapist would be alone

Allswang received psychotherapy at a practice where the owner also observed Orthodox Jewish sabbath.

The practice assigned a new caseworker to go to his house and help him develop job-seeking skills.

In the last week of June 2022, he was home alone, his brother at camp and his father and stepmother in New York. On Monday, he moved his home therapy appointment to Friday. On Wednesday, he went to Party City. There, he bought seven black disposable tablecloths — enough to cover 300 square feet of eating surfaces.

With his father’s and stepmother’s cars parked out front, the therapist wouldn’t know she was going to be alone with Allswang. His family, his neighbors and his therapist’s boss would stop answering their phones at sunset. They would be observing Shabbat. He would not.

Tzvi Allswang tells therapist: 'You need to be a good girl'

Allswang led the therapist to the den about 6:30 p.m.

He was unusually talkative. He also kept excusing himself to get water and to go to the bathroom.

He was still talking after the session ended. His questions became personal. He moved too close.

When she headed for the door, she saw what he had done when he excused himself.

He had taped sheets of black plastic tablecloths over the glass on the front door and windows.

Then Allswang tackled her from behind. He snatched her phone. He taped her hands behind her back in a praying position.

“You need to be a good girl,” he said.

He put her phone in airplane mode, wrapped it in foil and threw it in a drawer.

People would come looking for her, she said.

He demanded the passcode to her phone so he could text them. When she didn’t give it to him, he began to beat her.

Therapist's partner starts getting strange texts

The therapist’s partner had been trying to reach her for two hours when she got the first strange text message after 9 p.m.

The therapist hadn’t shown up for dinner. Friends hadn’t heard from her.

From 7:36 p.m. to shortly after 9 p.m., 36 calls and texts to the therapist’s phone had gone unanswered.

The text that finally came didn’t sound like her.

“OMG I got pulled over on my way cop thought I was drunk and taking me to station I’m going to take a blood test there cause cop is a dick . . . I’ll see you later.”

She didn’t answer 42 more calls and texts over the next three hours.

Her partner called law enforcement agencies in every jurisdiction the therapist might have driven through.

None had a record of any contact with the therapist.

A new text came at 12:28 a.m.

“Hey sorry I never got back to you I’m fine they got me a hotel room for all the shit they put me through Im still kind of shook Im staying here tonight I’ll see you tomorrow,” it said. “I’m going to sleep now goodnight . . .”

“That was a major red flag,” the partner told investigators. In five years together, they had spent no more than three nights apart when one was traveling.

The partner again called every police agency between Boca Raton and their town.

The therapist’s mother called Lantana police to report that her daughter was missing and appeared to be in danger.

Getting the address of that last appointment became crucial.

The therapist’s boss was observing Shabbat, the partner knew, “but I didn’t really care at that point, so I was just continuously blowing up his phone.”

Strict Orthodox Jewish religious guidelines offer an exception to avoiding technology during Shabbat — if a human life is in danger. Around 3 a.m., with his phone still ringing, the therapist’s boss realized that might be the case.

He answered.

The address he gave was under the jurisdiction of the sheriff’s office.

Inside the house near Boca Raton: Tzvi Allswang's emotions swing

Allswang’s emotions swung from calm to angry to sexually excited.

He got the password to the therapist’s phone after kneeing her in the stomach and banging her head against the floor until her vision blurred.

He attacked her with a large muscle massager that made her scream with pain.

He wanted her to take a nap with him and cuddle. He told her he was going to kill her.

He choked her from behind, his arm around her throat, and throttled her, his hands around her neck. He suffocated her, his hand over her nose and mouth.

She used therapy skills to reach him. She talked him into cutting the tape binding her wrists.

Now he threatened to mutilate her with the scissors he held.

Records check would have shown the danger

Deputy Travis Satterfield, who had started his law enforcement career with PBSO a year and a half earlier, headed for Larkspur Trail around 4 a.m. On the way there, he spoke with a Lantana police officer.

The officer told him:

The missing woman was a therapist who had not answered her phone since going into the Larkspur Trail house for a home visit with a client.

Two strange messages and nothing else had been received from her phone hours apart. She had not been booked into the county jail or admitted to a hospital.

No law enforcement agency in the county had a record of stopping her.

Her friends and family believed she had been kidnapped.

The therapist’s employer was waiting for him at the house.

In addition to the information from Lantana police, a routine check would have suggested that if the missing therapist was in the house, she was in danger. A judge had issued a restraining order against someone living there named Tzvi Allswang.

A system of databases operated by the sheriff’s office known as PALMS can reveal in seconds whether anyone at an address has a criminal record and what offenses they have committed.

For officers on calls that can involve potential conflict, knowing who lives at the address they are going to can be critical to their response and to their safety, according to Police Executive Research Forum Executive Director Chuck Wexler.

“Today police officers have so many ways to get information,” Wexler said.

A check can tell them whether law enforcement has been called to an address before and why, he said.

They would want to check a database, he said, “if they were talking to relatives and got information that the person is in danger.”

Wexler could not comment on a specific case, but PERF designs training to improve and standardize police procedures.

The training guides officers to methodically collect all available information, use it to assess risks and threats, and then apply laws and agency policies to guide their responses.

Nothing in dispatch records, reports and recorded interviews indicate those steps were followed that night.

The records do show that a PALMS report was produced on the missing woman as Satterfield drove to Larkspur Trail — it showed a traffic ticket.

No record indicates a PALMS check was requested on the Larkspur Trail address for more than four hours.

A PALMS report on the address requested by The Post shows Tzvi Allswang was the subject of a restraining order.

Another PALMS report on Tzvi Allswang himself, supplies the reason — his 2019 sexual battery conviction.

The full report of his arrest for the 2019 rape was also available to deputies.

As Satterfield headed for the house, there was no evidence he knew any of that.

Back inside the house: Tzvi Allswang punches, kicks, kisses her

Allswang had dragged the therapist from room to room by her hair, punching, pinching, kicking, kissing, groping and raping her for more than eight hours.

He wanted her to call him “Daddy.”

He accused her of turning his father against him.

In the master bedroom, she saw a clock. It was after 4 a.m.

Then she heard knocking on the front door.

If the sounds from outside gave her any hope, it did not last long.

Palm Beach County deputies get no answer to the doorbell

Deputy Angelo Marseille was in the last hour of his shift when he arrived as a backup officer at Larkspur Trail close to 4:20 a.m., minutes ahead of Satterfield.

A man waited in front.

Marseille learned that the man was a psychologist and the missing woman’s employer, who had sent her there to work with a client. The psychologist mentioned the suspicious texts, which neither he nor the therapist’s partner thought sounded right. He said the car in the driveway was hers.

Marseille ran two computer checks. One confirmed the car in the driveway belonged to the therapist. The next confirmed that she had not been arrested for drunken driving.

Satterfield arrived. They could see only their reflections in the black-shrouded front door glass.

They rang the doorbell, heard it ring inside, but nobody answered.

Satterfield called the officer he had spoken with earlier.

The car had been found, he said, but the therapist had not.

Therapist's partner to deputies: 'You're not going in?'

If the implication of the missing therapist’s car having been found in the driveway was lost on the deputies, it was not lost on her partner. It meant she was in the house.

A dispatcher connected her to Satterfield. She told him her girlfriend was in the home of a mentally disturbed patient "and you’re not going in?”

He did not have probable cause to do so, he said.

Friends gathered at the therapist’s and her partner’s home, and one placed the next call, demanding to speak to a supervisor. The missing woman was visiting a client who was seriously mentally disturbed, he said.

He was told to call back during business hours.

The girlfriend and five friends jumped into two cars and headed to Larkspur Trail.

No 'exigent circumstances' to barge into house

Marseille’s shift neared its end, and he called for a deputy to relieve him at the house.

Satterfield noted that the missing woman’s girlfriend had sounded “irate.”

He called his supervisor, Sgt. Vincent Haugh.

“They found her car (there),” Haugh would recount later, “but no threats of violence.”

He told Satterfield to write a report about his visit to the house and leave.

“We did not have exigent circumstances to make entry into the home,” Satterfield wrote. “I advised (the victim’s) boss to have a deputy return later in the morning if (the victim) is not heard from.”

Whether the knowledge that the missing woman's car was parked in front of a house occupied by a convicted rapist would have provided the exigent circumstances required by Florida law to get an emergency warrant to break into the house remains unclear. They still had not bothered to seek any information on the address or the client.

While Haugh would claim that he did not learn until much later that she was a therapist who had gone to the home of a client, Satterfield did know, according to his report.

Whether he didn’t tell Haugh during their conversation or Haugh did not consider it pertinent remains unclear.

The deputy sent to relieve Marseille never got out of his car.

The therapist’s partner and friends arrived at the Larkspur Trail house at 5:30 a.m. to find themselves alone outside.

Palm Beach County sheriff's dispatcher: 'You think she could be hurt?'

The girlfriend walked around the house and banged on the door.

As the morning grew light, she noticed a security camera on a neighbor’s home. She knocked on that door around 6 a.m., hoping the video would show whether anyone had left the house.

The neighbor told her it was Shabbat, and he could not help her.

She called Lantana police again.

An officer there called PBSO dispatchers at 6:47 a.m. to ask that they send a deputy back to the house.

“Is there new information?” the dispatcher asked.

“Yes, the reporting party is there. Her car is out front. She believes she is in there,” the officer said. “I’m sure you guys already have the information that the (missing woman) is with a client because she’s a mental health therapist — so we really want to make contact.”

“She’s a client?” the dispatcher asked. “Oh, she’s a therapist.”

“Lantana adv’d (the missing woman) is a therapist and believes she at (the address) with a (mentally disturbed) patient,” the dispatcher typed at 6:53 a.m.

The girlfriend called a recorded line a little after 7 a.m., her voice weak as she told a dispatcher how many times she had tried to get someone to listen to her.

She had been told the deputies would return. “It’s been a half hour. When are they going to show up?” she said. “She could be seriously hurt.”

“You think she could be hurt?” the dispatcher asked.

“Yes! She’s a therapist and she works for a severely mentally ill patient,” the girlfriend responded. “The patient is very dangerous to himself. That’s why he is under the care of the psychologist who met deputies earlier at the house. They said they couldn’t enter because they had no authority, but how long does it take to get authority?”

The deputies will be there soon and will tell her “what they can and cannot do,” the dispatcher said.

“So just be a little patient.”

The therapist's girlfriend seemed 'irate'

Cpl. Kenneth Udell and his trainee, deputy Austin Parent, arrived at 7:20 a.m.

The girlfriend seemed “irate” as she told them the missing woman was in the house, one noted.

“I asked how she knew she was in there. She said her car is there,” Udell said later.

Parent would recall hearing that her girlfriend was a mental health professional seeing a client in the house.

Where officers earlier had seen only darkness behind the front door glass, in daylight it was clear that a covering had been fastened over the window.

They walked around the side of the house to the back and knocked on a sliding glass door.

Inside, a woman screamed.

Deputies debate outside house west of Boca Raton: 'What kind of scream?'

It lasted about a second.

“Just one very loud scream,” Parent said later, “like an ear-curdling scream, I guess, if you want to put an adjective to it.”

Parent shouted: “Sheriff’s office!”

They pounded on the sliding door and tried to pull it open. Parent got on his radio to say they had heard a woman scream.

The inside of the house fell silent as they made their way around it, knocking on windows.

They appeared to consider breaking in through a window, noting later that the sound they heard when they knocked on the glass told them the windows were impact-resistant.

If they could have broken in, they would have, Udell said later.

“I didn’t have the tools,” he said.

The scream would have met the "caretakers" exception to the constitutional protection that prevents officers from entering a home without a warrant, an officer who arrived later would say. But the two officers there remained uncertain.

The girlfriend met them in front.

She had heard the scream. She begged the deputies to break in.

Udell called Haugh.

Haugh had one question: “What kind of scream?”

When they couldn’t answer, he decided to go there.

An alternative theory: 'Is this an affair?'

Haugh’s station was 10 minutes from Larkspur Trail. More than 30 minutes after Parent reported the scream, Haugh arrived, about 8 a.m.

Deputy Robert Banuchi showed up in response to the radio call.

A check on the cars told him that two young men with the same birthdate lived in the house — Tzvi Allswang and his twin.

The therapist’s employer, who had returned to the house, told Banuchi that Tzvi was the client.

Throughout the remaining two hours of the crisis, deputies would refer to the client by his twin brother’s name.

When Haugh arrived, he and the deputies discussed the scream. In his account later, Haugh appeared to be starting from scratch — he didn’t know the age of the people inside or the reason for the missing woman’s visit.

He had thought the call was a welfare check on the elder Allswangs, he said. Learning a young man was inside introduced a new thought.

“Is this a call for help?” Haugh asked, “Or is this an affair, she got caught?”

He asked Udell again.

“If you can tell me it’s a call for help, if you can write that s--- up,” he later said he told Udell, “we’ll f----ing kick the g-ddamn door in.”

Deputy told partner and friends to go get breakfast

The therapist’s girlfriend knew it was a cry for help. She and her friends shouted at the deputies to do something.

Their response, she recalled later, was to tell them to go get breakfast.

“They were laughing at us,” she said.

But inside the house, the therapist heard her girlfriend’s voice.

That gave the therapist the only hope she had left that she would survive, she said later.

Sergeant wanted 'minimal damage' — to the house

Haugh called his supervisor. They decided to call Palm Beach County Fire Rescue to bring a “little saw” to cut the lock out of the front door. That way, Haugh explained, they would do “minimal damage” in their effort to rescue the woman, who had screamed inside.

Haugh said he was only then learning why the missing woman had come to the house.

“So now we started getting more details,” Haugh recounted later. “The doctor, who is caring for this kid, so now we know, the kid is the patient . . . sent her here on assignment at 6 p.m. last night.”

Four more deputies arrived around 8:30 a.m. Questions finally were raised about the occupants of the house with requests for background checks on all of them.

At 8:29 a.m., a dispatch log notes, a PALMS report for Tzvi Allswang showed he had a record of a violent sexual offense.

At 8:35 a.m., a dispatcher for the first time refers to the situation on Larkspur Trail as “a possible false imprisonment.”

Still, they continued efforts to find the therapist elsewhere. This included “pinging” her phone to find its location.

“Now we’re doing extra,” Haugh explained later, “just trying to make sure this wasn’t (some young woman) who ran off with a 22-year-old.” (Allswang was 20.)

Rescue efforts halt to look for phone in Broward County

A deputy with a tool to break a window arrived. A Fire Rescue officer with a saw was on the way.

With plans forming to go in, deputies called for an officer with a canine. They called for a drone — a robot-like airborne camera — that could alert them to danger inside the house before they went in.

It was after 8:30 a.m. when a dispatcher told deputies that the phone’s signal had pinged off a cell tower in Deerfield Beach at 7 a.m.

PBSO deputies halted rescue efforts while Broward deputies searched for the phone that appeared to have sent a signal a half hour before a woman screamed in the home near Boca Raton.

“It’s nobody’s fault,” Haugh concluded. “Just checking all the f---ing boxes.”

'We are in the main part of the house'

While they waited, the deputies checked to see if anyone in the house had a concealed weapons permit. They sought a phone number for the homeowners. They checked local hospitals again. They requested another background check on the twin brother. They asked the Broward County Sheriff's Office whether the therapist was in that county’s jail.

At 9:13 a.m. they learned from Broward deputies that the ping came from a vacant industrial complex.

They prepared again to go in.

A radio recording captured this:

“Does any of them have a history of 35 (violent sex crime)?”

“Not that I’m aware, but I’ll triple-check.”

At 9:33 a.m., the door was open.

Still, they waited for the drone.

It wasn’t working.

The deputy equipped with the tool broke through a window.

A dispatcher again recorded an entry showing that Tzvi Allswang had been convicted in the past of a violent sexual offense.

At 9:39 a.m., a deputy reported over the radio: “We are in the main part of the house.”

Inside the house: Tzvi Allswang is excited deputies are breaking in

The sounds of deputies breaking into the house were exciting, Allswang told the therapist. He was going to get deputies to kill him, he said. But first, he was going to kill her.

Police knocked on the locked bedroom door.

Allswang covered her mouth, pressed his body against hers and pulled her into the closet.

He showed her the cleaver he had been carrying all night wrapped in a towel.

He made her hold one of his stepmother’s dresses to her body.

He held her in front of him, the knife against her throat.

She raised the hanger between the blade and her neck.

He forced it down.

She edged her thumbs against the blade.

That’s how deputies found her when they opened the closet door.

Palm Beach County sheriff's sergeant: It was like 'a horror movie'

A deputy with SWAT experience took over.

Haugh, directly behind that deputy, found himself staring at the man he had shown no interest in learning anything about throughout the night.

What he saw shook him.

“Completely emotionless,” he said later. “Honestly straight out of a f---ing movie. A horror movie.”

The SWAT deputy ordered Allswang to drop the knife. He told him: “You don’t have to do this.”

He talked to him for almost a minute.

Holding the therapist as a shield, Allswang kept the knife poised to cut her throat.

His size advantage had allowed him to control the therapist all night.

Now, the height difference gave the deputy a clear shot at his head.

Allswang fell to the floor when the bullet struck him.

The therapist ran.

Afterward: 'Microscopic slant' of bullet's path allowed Tzvi Allswang to live

“In the end, it was Allswang who made the decision to force the Sergeant to shoot him,” a State Attorney’s Office report on the shooting concluded.

“The result of a microscopic slant of the bullet’s trajectory was the odd quirk of fate that made the difference between a relatively minor, survivable gunshot wound and the death Allswang obviously preferred.”

A deputy led the therapist from the house. A paramedic pressed a towel to Allswang’s wound. Handcuffed to a gurney, complaining of pain, Allswang was loaded into an ambulance that sped to Delray Medical Center.

A paramedic gave the therapist a phone to call her partner and took her to another hospital.

Outside, law enforcement, fire rescue flood the street

The street that had been silent all night was now jammed with sheriff’s deputies and rescue responders’ vehicles. A bus was used as a command center where investigators began to gather information on the events and decisions leading to the shooting.

Investigators took statements from Haugh, Parent and Udell, and would take statements from Satterfield and Marseille, when their shifts began again.

Finally, a sheriff’s investigator listened to the therapist’s partner.

On a recording of their conversation, her voice is steady. She answers questions clearly and concisely. She recounts the chronology of the night, the strange messages, her many calls to her partner and her partner’s employer and her efforts through the early morning hours to persuade sheriff’s responders to rescue the woman inside the house.

The partner’s voice begins to break only after she says that the therapist had just told her she heard her urge the deputies to act.

“I just don’t understand how this could be the correct way to handle the situation,” the partner tells the investigator, “to have deputies telling us we should go for breakfast and brunch while this is happening, and chit-chatting with the neighbors who were outside drinking their coffee, watching us have mental breakdowns on the road, because no one is doing anything.”

The investigator reassures her: “We are looking into how the call was handled.”

Antigone Barton is a reporter with The Palm Beach Post. You can reach her at avbarton@gannett.com. Help support our work: Subscribe today.

This article originally appeared on Palm Beach Post: Palm Beach County deputies did nothing as woman was raped, tortured