Teachers are battling poor student behavior post-COVID. Delaware lawmakers strain for answers

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Dropped to the ground before a shaky cellphone video started, backpacks that could have been carried to class were instead trampled by students slamming closer into frame. One student fell on the bags, huddling on the floor as three other boys continued to punch, kick and stomp.

Another looked to be trying to break it up, his coffee soon launched out of his hand as the fight began. Some student onlookers gaped from the opposite side of the hall. Others just kept walking.

This was one shared video, said to be a Wilmington-area high school. It joins a pattern of growing reports, posts and discussion of incidents on school grounds.

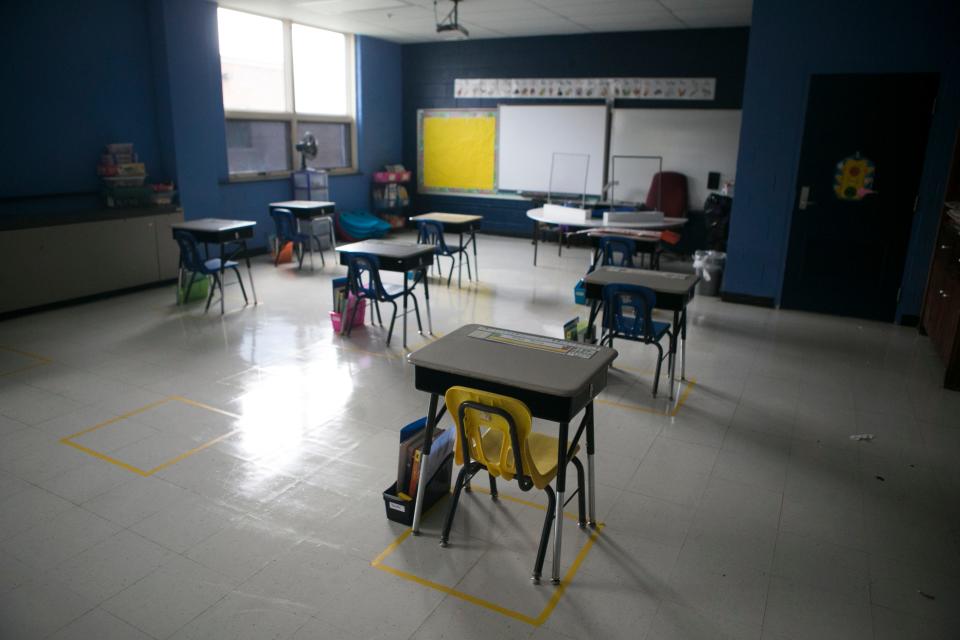

It’s not only fights, though. From thousands of other school hallways to Dover’s own Legislative Hall, calls for aid in student behavioral challenges seem locked in crescendo. General disrespect, lashing out, emotional deregulation: Educators say improving this school climate will be pivotal for both teacher retention and any shot at improving academic success.

It’s just not clear what can be done about it, yet.

This month, state lawmakers proposed a task force aimed at exploring such solutions. The “Student Behavior and School Climate Task Force” — as titled in a resolution that passed in the Senate on March 5 and House on Tuesday — joins a patchwork of proposals near this intersection, from both sides of the aisle.

"I think we all have been hearing throughout our districts, the issues of student behavior and overall the school climate,” said Senate Majority Leader Bryan Townsend in session, thinking of calls, contact with local leaders, videos circulating. The primary sponsor put forward a resolution very similar to that proposed by Sen. Eric Buckson, though the Republican's version did not pass.

“This is a critical issue statewide," Townsend said. "And this (will) establish a broad group of individuals statewide to work on that.”

Last school year, there were about seven suspensions for every 50 kids. Out-of-school suspensions alone were up 7.7% from pre-pandemic figures, though the most recent Delaware school discipline data ends in 2023.

Looking at crime specifically, arrests on school property are already up nearly 43% in 2023-2024 data, when compared with data in 2018-2019 from Delaware State Police. With over 330 arrests so far, however, the data is not limited to students, the school day or the standard school year.

Other impact doesn’t make its way into spreadsheets.

“It feels like some days the needs of the students are outstripping our capacity,” said Gloria Ho, certified school social worker at Milton Elementary. “Which is crazy. The frequency and intensity of student mental health issues are overwhelming.”

Educators want to know what Delaware can do about it.

Next read: Struggle for affordable child care persists in Delaware. That's for parents and providers

'Just the tip of the iceberg'

Elementary students are getting into a fight on the playground. Guided conflict resolution is needed after an incident in the cafeteria. Another student is shutting down, refusing to move from homeroom to social studies. There’s a list of those who need extra time, who need ongoing help with coping, with social competency, with self-harm risk.

But now another student is in crisis down the hall, acting out and breaking classroom items.

“Those are just the tip of the iceberg,” said Ho, a school social worker based in the Sussex County elementary with about 500 children.

“You're expected to return parent phone calls and emails within a day or two. We have to develop student support plans. Not only do we work with students individually, and have to enter data, we also have to attend school meetings. We have to address calls to the classroom to help regulate a student. And the big thing is, conducting suicide and behavioral threat assessments.”

Some of the hardest years in education came during pandemic shutdown. Now, Ho described a state of students in crisis — while counselors, teachers and educators are left with the “immense burden” of keeping them safe.

“As a mental health professional, I’m worried that something will slip through the cracks if the pressure isn't alleviated somewhere," Ho said. "Something has to give.”

Challenges don’t stick to grade levels.

Steven Byers understands the talk of an uptick in crises, in fighting, in violent incidents on school grounds — but the high school social studies teacher also said many problems start at basic expectations.

“Expectation of showing up to class on time: Something as simple as that can lead to friction between staff and students,” said the Appoquinimink union leader, noting that COVID-19 shutdown seems to have almost erased the concept of strict schedules. “And especially for the older students, you have disrespect towards adults. People in authority will be like ‘Hey, let's get to class,' and then in certain cases you'll have a kid say, you know, ‘FU!’ Immediate escalation.”

The Middletown High School teacher said students from K to 12 have returned with social-emotional learning deficits, many struggling with how to process stress or anxiety in general. Lashing out takes on different forms across levels, across individuals.

It isn't Delaware's problem. Nationwide, the National Center for Education Statistics cited a 56% increase in classroom disruptions from student misconduct within the ‘21-2022 school year, while rowdiness outside of the classroom grew by 48%.

One might expect student discipline data to follow such spikes.

Out-of-school suspensions were up just under 8% from pre-pandemic figures by 2023, according to state data. There were seven fewer expulsions than in 2018-2019, with in-school suspensions down 1.7%.

Suspensions that resulted in alternative placement — relating often to more extreme incidents or chronically repeated behavior — were up nearly 27% in the same period. That’s 230 kids last year, still far smaller than typical suspensions statewide, which totaled nearly 21,300 students overall with in-school and out-of-school suspensions.

This data, alongside the growing concern with post-pandemic student behavior, is also landing in a moment of evolution in student discipline.

That’s a movement from punitive or exclusionary styles to more restorative practices, as explained by Rosalie Morales, the Department of Education’s education associate for school climate. Back in 2018, public schools were charged with improving school discipline, tracking data on disciplinary action, and pushing back on exclusionary practices with disproportionate discipline faced by students of color. Another report is expected this fall, highlighting schools with disproportionate outcomes.

More on the data: Some Delaware students are suspended far more than others. How schools are addressing this

“Since I've started, we've been bringing in experts to focus on moving away from punitive and focusing on ways to restore relationships, bringing in those restorative practices that districts began implementing,” said the associate hired last fall.

From behavior threat assessments to boosted support for mental health and interventions, Morales described aims to address challenges early — “so that we're not having them escalate to higher-level incidents later, that may result in maybe a suspension or an expulsion.”

It’s a movement many educators want to keep at the forefront.

They just might need more help.

Flashback: ACLU points to one Delaware charter school to spotlight lessons in inclusive culture

On the search for solutions in Delaware schools

She catches herself thinking of other statistics.

Back in the halls of Milton Elementary, Gloria Ho remembers reading that some 55% of educators surveyed are ready to leave their profession earlier than planned. It was a 2022 poll by the National Education Association.

“And each day, I feel personally like I get closer to being part of that statistic,” she said.

Ho believes many educators are growing exhausted and disillusioned. The social worker stressed that safeguarding teacher well-being must also be central to Delaware’s response, though she doesn’t pretend to have all the answers.

If the task force has a chance, she and other educators agreed, it will come down to representation.

“Just make sure that there are educators at the table,” Ho said. “And when I say educators, I mean the teachers, social workers, the paraprofessionals, figuring out how to deal with increased student mental health issues and disciplinary action. But, it has to be done in a way that lessens exclusionary practices. I don't want to go backwards.”

The work should begin this spring. And according to SR119, the task force would owe the state its recommendations by November.

Another supporting senator would agree with Ho's assessment.

“I think the advantage of the task force is we get a lot of voices in the room, and we can invite lots of educators to speak,” said Sen. Laura Sturgeon. The Democratic lawmaker and former educator of 25 years knows this will be a sensitive issue to tackle.

“I hope we'll be talking about all the preventative things you can do, restorative and trauma-informed practices you can do on the front end,” Sturgeon said. “But we also have to talk about OK, (if) you've done all that, but you still have students who are misbehaving, what do we do on the back end?”

Thoughts turn to codes of conduct, to best practices that might be working for some schools, to resources and educator support still needed. “There's so many aspects of this,” Sturgeon said. “I'm not sure our work will be done by November.”

Until then, the school year simply continues.

Next read: Creative library project underway in Wilmington to spur community and economic development

Got a story? Kelly Powers covers race, culture and equity for Delaware Online/The News Journal and USA TODAY Network Northeast, with a focus on education. Contact her at kepowers@gannett.com or (231) 622-2191, and follow her on Twitter @kpowers01.

This article originally appeared on Delaware News Journal: Will a task force on student behavior help Delaware public schools?