Delaware agencies paid out more than $3M in 3 years for injuries by police. Here's why

In the past three years, Delaware's four largest police departments have quietly paid out more than $3.2 million in legal settlements to people who claimed physical harm by police, according to a review of agreements turned over through state public records law.

In a state that allows its police wide latitude to investigate themselves and withhold most basic documents detailing their work, the cases that led to those settlements give the public a rare window into allegations of excessive force by police.

Uses of force and police crashes drive total:

The settlement total for the four departments includes a previously unreported $975,000 payment to dismiss a lawsuit filed by the family of a man who died − and who a judge said may have already been restrained − when a Delaware State Police officer tasered him for a third time in 2015.

It also includes a $650,000 payment to dismiss a lawsuit filed by a man who was a teen when he was shot at four times and struck twice by a Wilmington officer while fleeing in a stolen car in 2019.

Police cars (specifically, their drivers) are prominent:

The settlement total includes a previously unreported $700,000 payment to the family of a child that suffered a traumatic brain injury when a Wilmington Police chase ended in a multi-car pileup on I-95 near the Philadelphia International Airport in 2019.

It also accounts for a previously unreported $290,000 payment to dismiss a lawsuit filed by a man that was permanently injured after being pinned between a brick wall and a Wilmington Police cruiser during a 2018 chase.

The total includes $400,000 paid by Delaware State Police to dismiss a lawsuit filed by family of a child killed in a crash caused by a state police officer in 2017, according to the family's lawsuit.

Each department had multiple five- or four-figure payouts for crashes by officers.

While many of the highest payouts stem from incidents that made the news, smaller settlements and unheard-of cases are included in the total:

Those include a $27,000 payment to dismiss a lawsuit by a man who claimed he was pulled over by Dover Police while riding a bike, shocked with a Taser, beaten and had officers plant a gun on him, according to allegations in the man's lawsuit, which police denied.

Dover Police also have two other settlements totaling $22,000, stemming from people who claimed they were unnecessarily harmed by officers.

Wilmington paid $30,000 to dismiss a lawsuit filed by a woman who claimed she was coerced into performing oral sex on a Wilmington Police officer in his police cruiser, the only case in this tally that also saw the officer criminally prosecuted directly for the harmful conduct.

New Castle County paid out $25,000 to dismiss a lawsuit filed by the family of a teen seen on video being punched by officers and another $11,000 to settle a case involving officers allegedly busting into a Wilmington man's home, guns at the ready, before taunting the man once they'd realized they were in the wrong place, according to his lawsuit and reporting by the Associated Press.

State Police paid out $45,000 to dismiss a lawsuit filed by a father and mother duo that claimed a SWAT team unnecessarily injured them as part of a burglary investigation in 2015.

Keep in mind: The settlement totals reflected above account for how much municipalities agreed to pay out and not necessarily what those suing received. Ultimately, the amount those suing receive is far less. Attorneys also receive large chunks of the payout total.

Other settlements: This tally includes only cases where police are alleged to have caused injury. Police departments have settled personnel matters for large sums during that period, including New Castle County police paying well more than $1.5 million to settle a sexual harassment lawsuit filed by a former officer, and those are not reflected in this story.

PERSONNEL SETTLEMENT: For a second time, Dover settles white officers complaint over promotion of black officer

Who pays police misconduct settlements and do they admit fault?

In each of the cases mentioned above, attorneys representing the departments and the officers involved denied wrongdoing and liability in court filings. The settlements also explicitly admit no fault.

But that doesn't mean there isn't fault.

The law provides police departments and officers wide-ranging legal protections through things like qualified immunity that see many lawsuits fail on technicalities before evidence is shared among the parties or gets close to an evaluation by an impartial jury.

In recent years, most police misconduct civil allegations have been dismissed or settled before they reached the presentation of evidence to a jury in civil court.

The three municipalities, Wilmington, Dover and New Castle County, each treat police misconduct settlements as part of business and pay an annual premium for insurance though each setup is different.

For example, Wilmington is self-insured but pays $318,000 annually for coverage of claims that exceed $750,000. It is unclear exactly what fund state police settlements go through.

Dover pays for insurance to cover various areas of city government including cybersecurity, auto liability and property damage, as well as law enforcement liability. The city pays about $900,000 annually for such coverage, according to city officials. The city's deductible for police liability is $15,000.

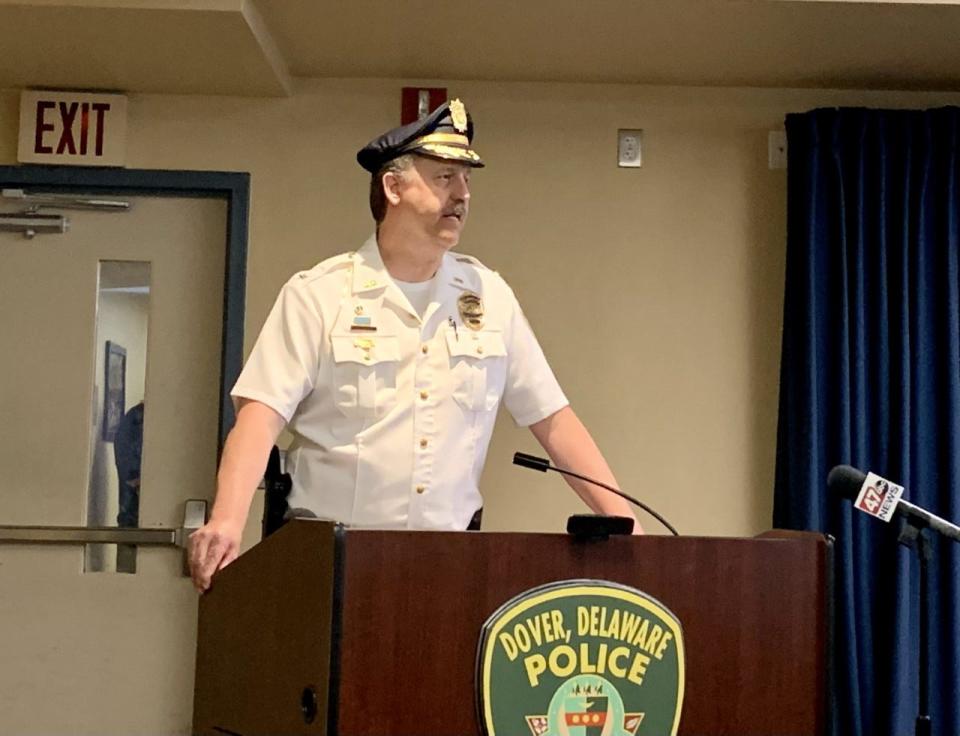

In an email, Dover Police Department Chief Thomas Johnson, Jr. said "lawsuits" will always be with "us," given police officers' enforcement authority and municipalities' financial resources. He noted that the city's insurer "takes over" in such cases and that his department is "not involved" in the final disposition of the lawsuit.

"Litigation is costly, for both sides, and settlements usually represent a business decision rather than a true reflection of the merits of any particular case," Johnson wrote.

Implications regarding police transparency in Delaware

Civil litigation gives the public a rare window into how the police in Delaware police themselves and, to a limited extent, the outcomes.

A suite of state laws known as the Law Enforcement Officers Bill of Rights (LEOBOR, for short) dictates that police discipline be conducted in-house and records kept confidential.

The Delaware Department of Justice, the state's prosecutorial arm, typically only gets involved when there is deadly use of force and limits their evaluation to whether the officer's conduct could break criminal law.

So when it comes to complaints about excessive force or abuse of power, departments investigate themselves and records reflecting complaints against officers, how rigorously those complaints were investigated and the outcome are all kept secret.

In theory, we can learn a lot about individual cases when people take the police to court. But that really depends, as each case is different.

In some civil cases, litigation includes expert reports that directly criticize officers' actions, training and the department's internal investigation into officers' use of force.

In some cases, that information is shared in evidence but never makes it beyond the eyes of attorneys. In others, cases settle or are dismissed on a legal technicality before any evidence is shared with the plaintiff.

In some civil cases, excerpts of officer statements, their actual police reports − documents that are otherwise kept secret in Delaware − are included as exhibits in the litigation. These can provide more insight into an incident but it can also raise more questions.

The case of Lionel Waters, who was tasered three times by a Delaware State Police officer in 2015, is an example of that. After his death, a Department of Justice report indicated that he was resisting officers, prompting the final Taser burst. After years of litigation, a ruling by a federal court judge denying a request to toss a lawsuit filed by Water's family noted that a reasonable jury could conclude that Waters was "secured" before the final Taser burst.

Victims' voices are typically gagged by confidentiality clauses baked into the settlements. The clauses mean the plaintiff could risk their payout if they speak about the case. The confidentiality agreements also bind departments, some of which cited those clauses in declining to comment for this story.

Johnson, the Dover chief, said such agreements cut out "harmful rhetoric" once legal proceedings have concluded. Critics say they stifle necessary discussions about policing.

Should the Delaware General Assembly intervene?

Johnson wrote that he "endorses the use of the legal system to address grievances against law enforcement," calling it "safer and more effective." Those who have been advocating for police reforms disagree.

In recent years, that effort has been aimed at reforming LEOBOR, the law which makes Delaware unique in mandating complete police secrecy regarding officer discipline. Those advocates want more public access to police complaints and disciplinary decisions and for community boards to have a say in that process."In many of these cases we have no idea how, or if, these officers were disciplined for the conduct that led to these settlements," said Kevin O'Connell, who leads Delaware's Office of Defense Services, the state's public defender.

RECENT: How public almost never learned about police officer charged in two excessive force incidents

O'Connell also noted that the public has no insight into individual officers' history and whether there are patterns of similar complaints against them. Civil cases sometimes touch on such records, but often do not. This is important because O'Connell's clients have a right to know relevant aspects of an officer's history when those officers are testifying against them in court.

Haneef Salaam, manager of ACLU Delaware's Campaign for Smart Justice and an advocate for reforming LEOBOR, said reform is about establishing trust. The settlements only include misconduct that leads to injury. He believes there are more allegations and instances of misconduct that don't make it to court.

Community review boards would have at least some eyes on the process: the complaints, whether they are legitimate, and if they are both investigated and handled properly. He said it is important for people to be able to see the process to be able to trust the process and outcome, as well as to make sure different departments don't have discrepancies in how they handle similar situations.

This debate has been ongoing and may continue:

Last year, Delaware lawmakers came the closest they ever have to reforming police transparency laws, though the effort was pulled before lawmakers had to cast a vote. Many blamed the inaction on law enforcement and a contingent of Democratic legislators who have professional or political ties to law enforcement.

An early version of the bill, championed by Wilmington Sen. S. Elizabeth "Tizzy" Lockman, would have opened up police complaints and disciplinary actions to public review and empowered local governments to create civilian review boards, which would have access to complaints, subpoena power to investigate those complaints and the authority to make decisions on police discipline.

LEOBOR REFORM: Latest police transparency proposal would keep historic officer complaints hidden

Later, that was watered down to expose fewer police documents and give review boards fewer teeth, and the effort ultimately fizzled.

Police backers criticized the reforms, raising fears that individual officers would be open to "public ridicule" by people who have something against the officer. They also criticized the idea of non-police having some sway over how departments operate.

Reform advocates do not expect the debate to be over though Lockman, who is now Senate majority whip, has not introduced a new version of the bill in this legislative session.

Contact Xerxes Wilson at (302) 324-2787 or xwilson@delawareonline.com. Follow @Ber_Xerxes on Twitter.

This article originally appeared on Delaware News Journal: Delaware police paid more than $3M in settlements for injury cases