A defender of the under-served, this lawyer was also a concentration camp liberator

Our Uniquely Fort Worth stories celebrate what we love most about Cowtown, its history & culture. Story suggestion? Editors@star-telegram.com.

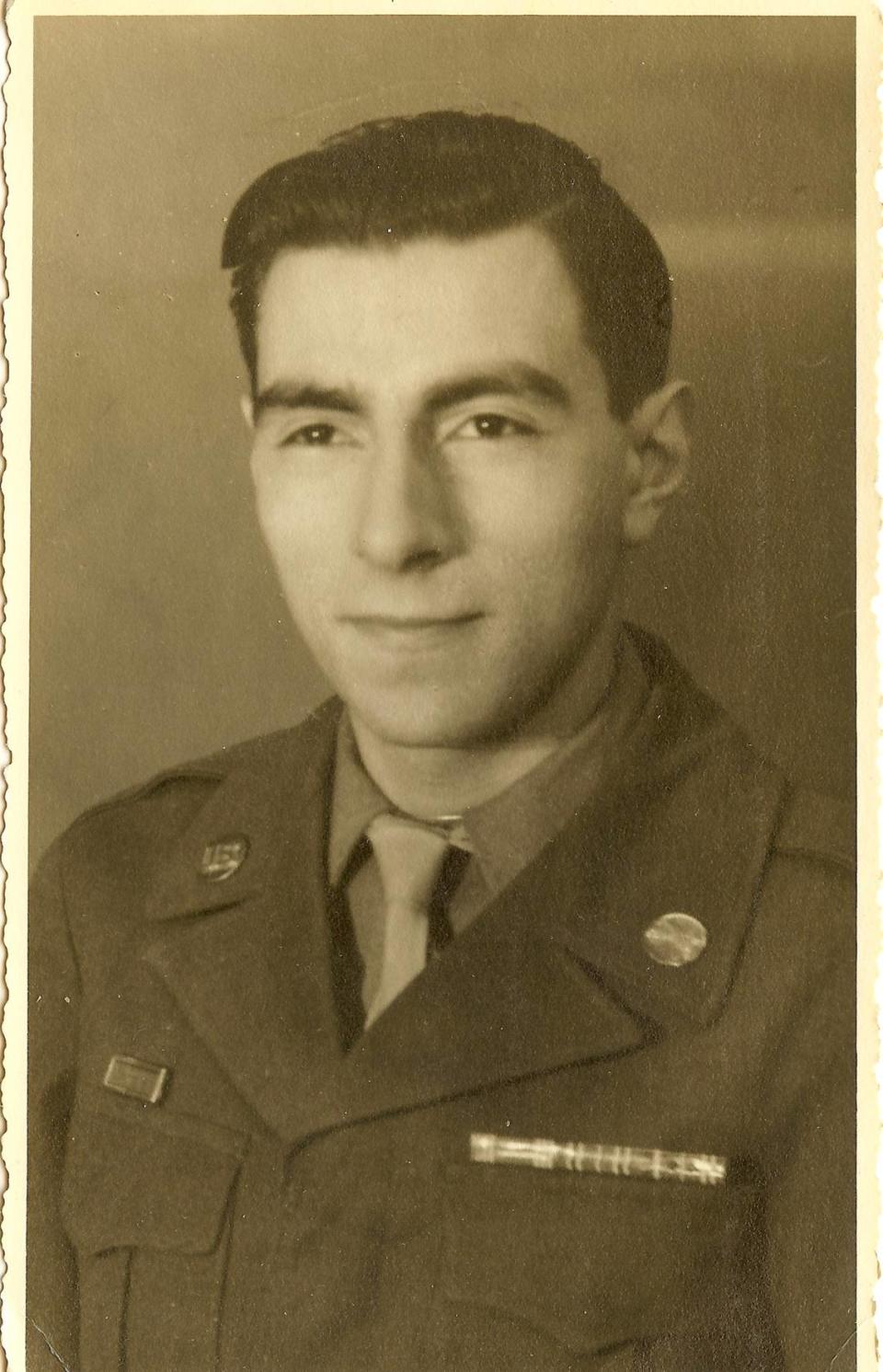

Attorney Jerry Murad (1926-1994) was well known across Tarrant County as “Honorary Consul of Mexico,” an unpaid post representing Mexicans in Texas who were injured on the job, beset with immigration woes, or facing prison.

His advocacy led to freedom for a Mexican national jailed in a case of mistaken identity. A dynamic trial lawyer, he was such a successful defender of the under-served and undocumented that on Nov. 7, 1987, Mayor Bob Bolen declared “Jerry Murad Day in Fort Worth.”

Murad understood the difficulties that marginalized people face in America, for his own father was an Arabic-speaking, Jewish immigrant from Baghdad, the capital of Iraq.

Less known among his colleagues was Jerry Murad’s service in World War II. Because he had poor vision, he memorized the eye chart to pass his Army physical. As a corporal assigned to an armament division, he drove a half-track. Whenever asked about combat, he steered the conversation to the lighter side with tales of the mademoiselles he met during furloughs in France.

He was reluctant to describe the horrors of war until one night in New York in 1982 while he and his law partner, Randy P. Parker, were relaxing over drinks at the Waldorf Astoria.

“After a long day of depositions and some funny stories about his WWII times, I asked Jerry to tell me what were some of the worst times he experienced in the war,” Parker recently recalled. “I wondered if Jerry would talk about combat.”

He never had before.

“His facial expression changed immediately from his usual jovial self to a serious look,” Parker said. “He told me that the worst thing he saw was when he and a group of soldiers were the first to come upon a concentration camp. They saw the fences and prisoners looking through the barbed wire. They looked like skeletons with uniforms hanging on them, but their deeply sunk eyes, so sad and near death, seemed to recognize that the Americans were coming and that they would be saved.

“Jerry said that it was all so horrible, with the starving prisoners, the piles of dead bodies and the smell. He almost threw up, but he held back because, as a Jew, he wanted to show strength at that moment. ... It also made him very angry. It was the worst thing he ever saw in the war and in his life. Jerry was near tears as he told me how he felt. So was I, just seeing his pain at talking through that memory.

“Then, typical of Jerry, he quickly ordered another round of drinks and changed the subject to a lighter story about some experiences he and a soldier friend had with some liberated French girls in Paris.”

Murad and his law partner, who now resides in Helotes, rarely spoke again about the Nazi death camps, although in his mind, Parker replayed the conversation over and over.

“Hearing Jerry’s first-hand account of coming upon that horrific scene is something I will never forget. It is far more powerful and vivid to me than all the films I have seen that have documented the Holocaust,” Parker said. “I believe that Jerry was able to handle his years-long fight with cancer, ... filled with telling jokes and funny life stories to entertain family and friends, right up until the end of his life in 1994 due in great part to the powerful impact of having helped liberate a Nazi death camp — a truly life-changing experience.”

Texas Liberators

Murad’s experience, not previously reported, may qualify him as a Liberator, the official designation for the Allied soldiers who first encountered the Nazi death camps. The Army’s Center of Military History and the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum created the designation in 1985. A Texas Liberator’s Honor Roll, being compiled by the state Holocaust and Genocide Commission (https://theliberatorproject.org) has identified more than 500 Texas veterans who participated in the liberation of 43 different camps.

In order for Murad’s name to be added, researchers at the Ackerman Center for Holocaust Studies at the University of Texas at Dallas are tracking down the armament division in which he served. The veteran’s son, Jerry Murad Jr., 58, also a Fort Worth attorney, said his father had mentioned to him that he had witnessed a concentration camp, but little more. The son does not have his father’s military discharge papers, nor does he know the division or units in which he served. Last month, he applied to the National Archives and Records Administration for that information. The National Archives receives more than 5,000 requests a week for veterans’ records, and the answer may take months.

Gerald “Jerry” Murad was born in New York City on July 19, 1926. His parents, Harry, of Baghdad, and Lena, a native New Yorker, operated a succession of baby boutiques in Philadelphia, Chicago and Milwaukee. After Jerry’s high school graduation, he enlisted on Aug. 21, 1944, from Fort Sheridan, Illinois. Following the war, the family moved to Fort Worth, where his father had relatives — George and Aaron Rashti — who were also born in Baghdad. The Murad family became congregants at the city’s two synagogues, Ahavath Sholom and Beth-El.

Jerry attended Texas Christian University and West Texas State University, graduating in 1951. He received a law degree from Baylor University and was a Tarrant County assistant district attorney from 1953 to 1957. Always sociable and involved, he was a Scottish Rite Mason, an honorary Fort Worth police officer and founding president of the Tarrant County Trial Lawyers Association.

Hollace Ava Weiner, director of the Fort Worth Jewish Archives, is an author, archivist and historian.